by M. Abdullah Khalid

At midnight of August 15, 1947, the largest recorded forced migration in modern history began. Millions of Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs were forced to journey hundreds of miles and experience brutal violence as the Indian subcontinent was divided into two independent nation states following the dissolution of the British crown rule on the part of the United Kingdom. The partition involved the division of two provinces, Bengal and Punjab, based on district-wise non-Muslim or Muslim majorities. The self-governing countries of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan came into existence. The partition also saw the division of the British Indian Army, the Royal Indian Navy, the Indian Civil Service, the railways, and the central treasury. As a person from this region, I am closely related to this event, and in this blog I will tell a different and lesser known story about the impacts of partition on the mighty Indus river system that connects the Indian Subcontinent.

The affluent waters of the Indus system of rivers begin primarily in Tibet and the Himalayan mountains in the states of Himachal Pradesh in India and the disputed territories of Jammu and Kashmir. They flow through the states of Haryana and Rajasthan in India, Punjab that is shared by both countries, and then Sindh in Pakistan before emptying into the Arabian Sea south of Karachi and Kori Creek in Gujarat. As the river moves downstream it carves out a valley. People have settled here for thousands of years and laid the foundation for the Indus Valley Civilization. The first farmers settled near the river because it kept the land fertile for growing crops. These farmers lived together in villages which grew over time into large ancient cities, like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro in modern-day Pakistan. The Indus people needed river water to drink, wash, and to irrigate their fields. They may also have used water in religious ceremonies. The Indus people referred to the river as ‘The King River’.

1947

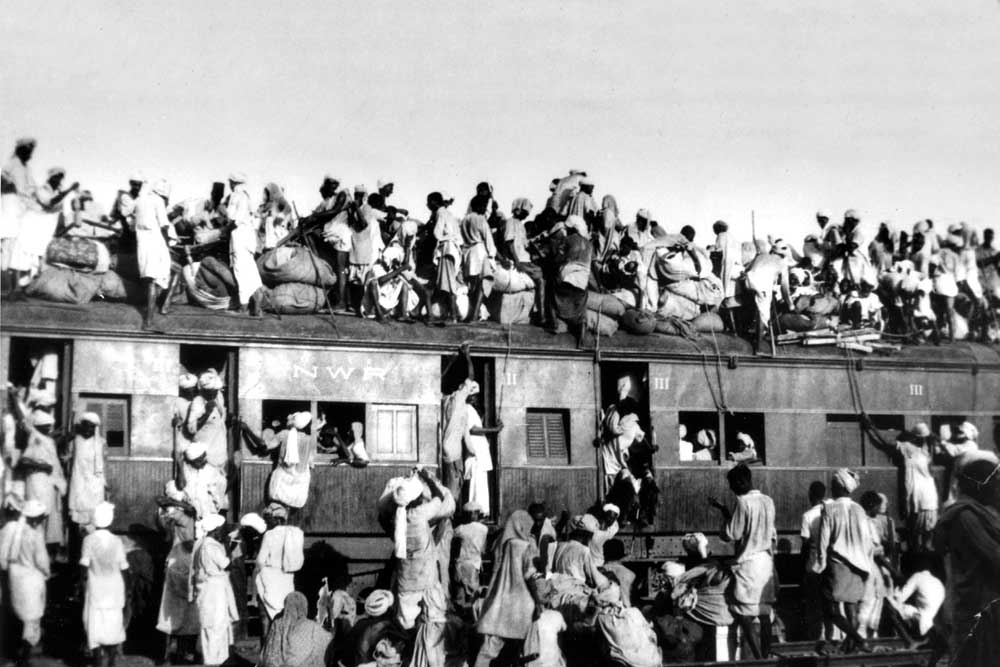

During partition, communities that had coexisted for a thousand years succumbed to an eruption of sectarian violence. More than a million people were killed and between 10 and 12 million people were displaced along religious lines, creating an overwhelming refugee crisis in the newly constituted dominions. The violent nature of the partition created an atmosphere of hostility and suspicion between India and Pakistan that plagues their relationship to the present.

While extensive scholarly work has been conducted to investigate the human rights atrocities committed by both sides, less has been done to document how nature, and in particular rivers, suffered at the hands of the partition. The impacts of this chaos on the mighty river Indus were not addressed until 13 years after the partition when both states finally realized that water was a matter of life and death for their new-born agriculture-based economies.

Muslim refugees clamber aboard an over-crowded train near New Delhi in an attempt to flee India (Open Magazine)

According to a World Bank report published in 2014, the average annual available water resource in Pakistan is 218.4 billion cubic meters. Developments over the last century have created a large network of canals and storage facilities where there was once only a narrow strip of irrigated land along the rivers. Since 2009, this infrastructure has provided water for more than 47 million acres (190,000 km2) of agricultural land in Pakistan alone, making it one of the largest irrigated areas of any one river system in the world.

1960 - Indus Water Treaty

The partition of British India created a conflict over the waters of the Indus basin. The newly formed states were at odds over how to share and manage what was essentially a cohesive and unitary network of irrigation. Furthermore, the geography of partition was such that the source rivers of the Indus basin are located in India. Pakistan felt that its economic possibilities would be threatened by the prospect of Indian control over the tributaries that feed water into the Pakistani portion of the basin. India had its own ambitions for the development of the basin in the form of dams and barrages, and Pakistan felt acutely threatened by a conflict over the main source of water for its cultivable land.

The course of the Indus River and its main tributaries.

During the first years of partition, the waters of the Indus were apportioned by the Inter-Dominion Accord of May 4, 1948. This accord required India to release sufficient waters to the Pakistani regions of the basin in return for annual payments from the government of Pakistan. The accord was meant to meet immediate water needs and was followed by negotiations for a more permanent solution. However, neither side was willing to compromise their water access and negotiations reached a stalemate. From the Indian point of view, there was nothing that Pakistan could do to force India to divert the river water into the irrigation canals of Pakistan. Pakistan wanted to take the matter to the International Court of Justice, but India refused, arguing that the conflict required a bilateral resolution.

Clauses of the IWT

The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) was finally signed in Karachi, Pakistan on September 19, 1960 by the first Prime Minister of India, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, and then President of Pakistan, Ayub Khan. According to this agreement, control over the water flowing in three “eastern rivers” of India — the Beas, Ravi, and the Sutlej with the mean annual flow of 33 million acre-feet (MAF) — was granted to India, while control over the water flowing in three “western rivers” of India — the Indus, Chenab, and the Jhelum with the mean annual flow of 80 MAF — was granted to Pakistan. More controversial, however, were the provisions on how the waters were to be shared. Since Pakistan’s rivers receive more water flow from India, the treaty allowed India to use western rivers water for limited irrigation use and unlimited use for power generation, domestic, industrial and non-consumptive uses, such as navigation, floating of property, and fish culture, while laying down precise regulations for India to build projects. The preamble of the treaty declares that the objectives of the treaty are to recognize the “rights and obligations of each country in the settlement of optimum water use from the Indus System of Rivers in a spirit of goodwill, friendship and cooperation.” Despite this diplomatic premise, Pakistan continues to fear that India can create floods or droughts in its territory, especially at times of war between the two countries, given that substantial water inflows of the Indus basin rivers are derived from India.

Signing of the Indus Water Treaty, 1960 in Karachi, Pakistan

A daily retreat ceremony at the India-Pakistan joint border check post of Attari-Wagah

Since the ratification of the treaty in 1960, India and Pakistan have not engaged in any official water wars. Most disagreements and disputes have been settled via legal procedures provided for within the framework of the treaty despite three wars and many war-like situations for other reasons, including territorial disputes. The treaty is considered to be one of the most successful water sharing endeavors in the world today, even though analysts acknowledge the need to update certain technical specifications and expand the scope of the document to include climate change mitigation strategies.

Implications - Use of Water as a Weapon of War

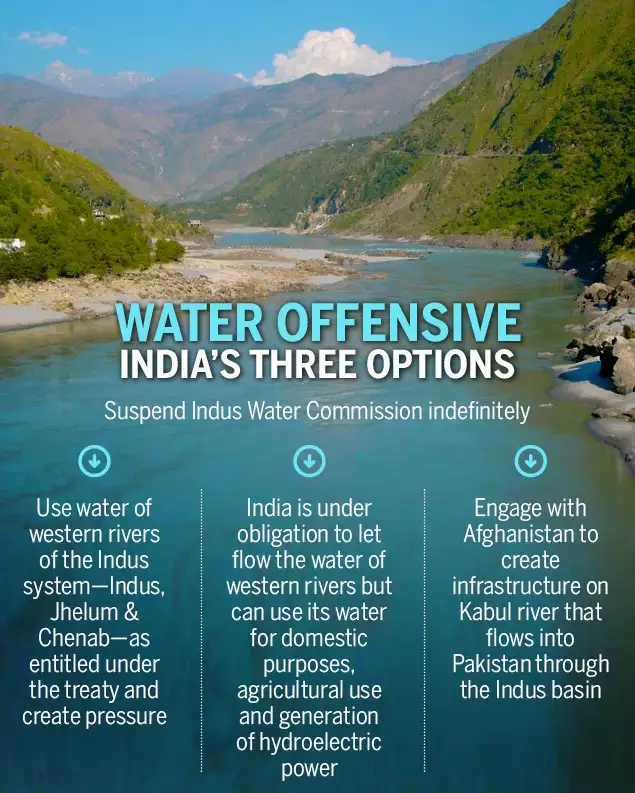

This said, in the aftermath of the September 18, 2016 attack by four heavily armed terrorists near the town of Uri located in the then Indian administered states of Jammu and Kashmir, India threatened to revoke the Indus Waters Treaty, claiming that the violence was backed by the Pakistani government. The current Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared, "blood and water cannot flow together." Thus far, a suspension of the treaty has not materialized. However, India decided to restart the Tulbul Project, which is a barrage with an expected storage capacity of 300,000-acre ft (370×106 m3) of water on the Jhelum River in the Kashmir Valley, that had previously been suspended in response to Pakistan’s objections. Similarly, in the aftermath of a February 14, 2019 attack on a convoy of vehicles carrying security personnel on the Jammu Srinagar National Highway by a vehicle-borne suicide bomber in the Pulwama district, Jammu and Kashmir, then Indian Minister of Roads and Water Resources, Nitin Gadkari, declared that all water presently flowing into Pakistan from the three eastern rivers would be diverted to Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan in India for various uses. Hasan Askari Rizvi, a political analyst in Lahore, Pakistan, has explained that any change to the water supply of Pakistan would have a "devastating impact" on the millions of Pakistanis who directly and indirectly depend on the river.

Indian government formulating ways to violate the Indus Water Treaty (Times of India)

Abuse of the Rights of Rivers and its Relations to Floods

Poor decisions made by both governments for political and economic gains have had devastating impacts for local riverine communities on both sides of the border for the past 72 years. It is possible to link the floods occurring almost every year in the subcontinent to the misuse of the Indus Water Treaty, or better yet, to the violation of rights of the river. Despite the fact that the causes of the floods have primarily been linked to unusually strong monsoon spells, there is a need to study the impacts of India’s construction of hydroelectric dams in the basin.

A girl floats her brother across flood waters whilst salvaging valuables from their flood ravaged home in the village of Bux Seelro near to Sukkur, Pakistan (Guardian)

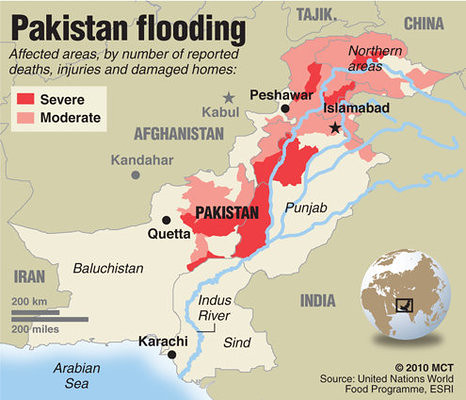

Areas affected by the 2010 floods in Pakistan (Source: United Nations World Food Programme, ESRI ⓒ 2010 MCT)

2010 - Pakistan Floods

The floods in Pakistan began in late July 2010, and approximately one-fifth of Pakistan's total land area was affected. According to statistics produced by the Pakistani government, the floods directly impacted about 20 million people, mostly in the form of the destruction of property, livelihoods, and infrastructure, with a death toll of close to 2,000. The World Health Organization reported that ten million people were forced to drink unsafe water, and the Pakistani economy was deeply harmed by extensive damage to infrastructure and crops.

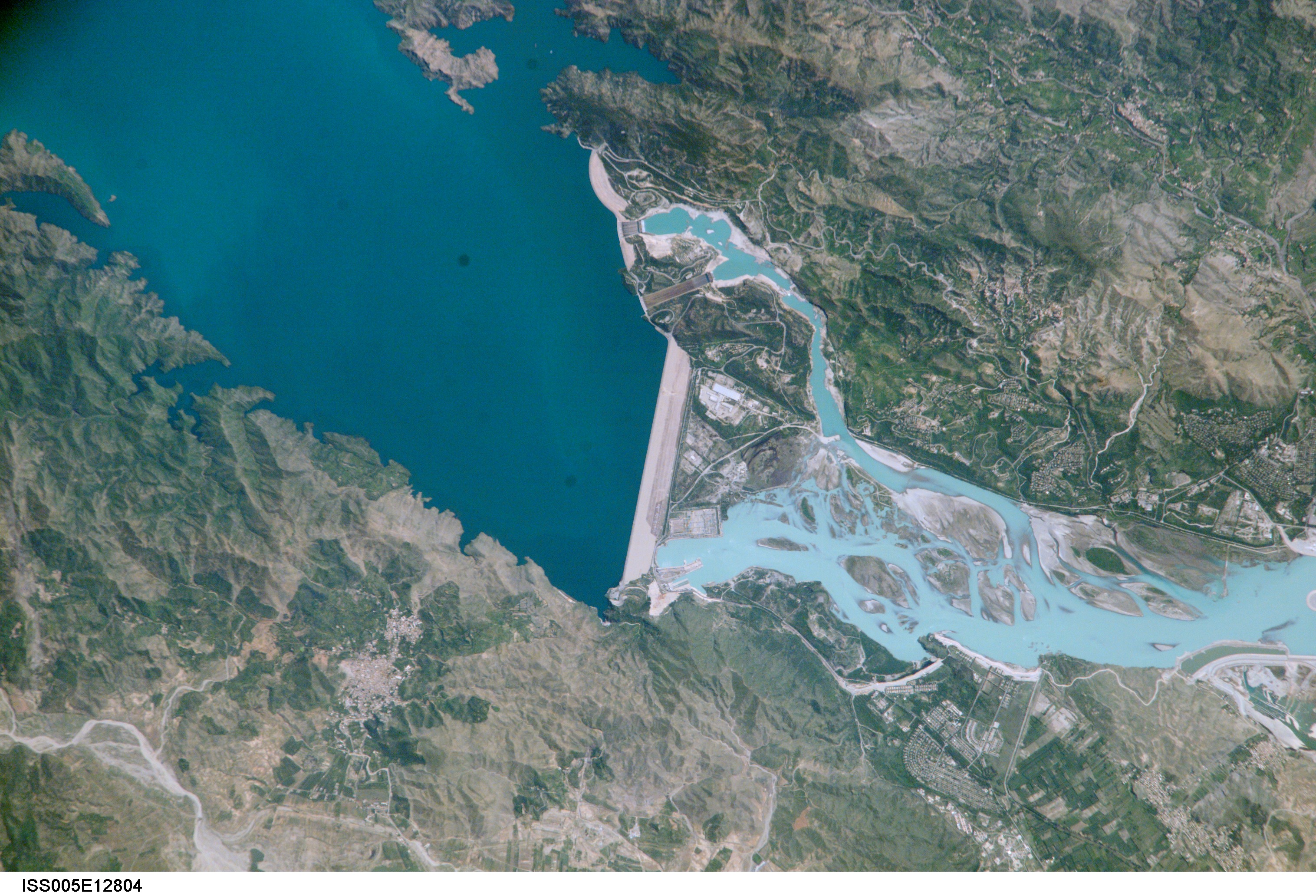

By building dams and barrages and manipulating the treaty for political interests, both governments have diverted the natural flow of the River Indus. This has destroyed the river’s ecology, displaced people whose livelihoods depend on the river, and impacted the biodiversity of the Indus Delta in the name of national interests and “sustainable” development. In reaction to this situation, several local communities and environmental non-profit organizations are arguing that there is need for the River Indus to be restored, so that the river flows from start to tail end following its natural course. They also defend the need to recover the biodiversity of the basin as well as the livelihoods of riverine communities. Earth Law Center, an international non-profit organization that aims to transform legal codes to recognize and protect nature’s inherent rights to exist and flourish, has partnered with Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum, a non-governmental organization that works to advance the social, economic, cultural and political rights of fishermen and fishing communities in Pakistan. The Indus River has suffered from severe declines in both water levels and quality and continues to face severe threats, such as unplanned irrigation and unsustainable dam construction. Thus, as long as the law treats the Indus River as mere property to be exploited for profit and political gains, it will continue to be diverted, dammed, and polluted by both States.

Tarbela Dam, an earth-filled dam along the Indus River in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province (NASA Satellite image)

To address this situation, Earth Law Center and Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum are working with other partners to achieve the recognition of the legal rights of the Indus River. They have written a draft called the “Indus River Rights Act” that is under review by political leaders in Pakistan.

The draft law recognizes the inherent rights of the River Indus, which include:

- The right to flow

- The right to perform essential functions within its ecosystem

- The right to be free from pollution

- The right to feed and be fed by sustainable aquifers

- The right to preserve and restore native biodiversity

- The right to be restored

Earth Law proposes placing guardianship of the river in the hands of local riverine communities in partnership with the Pakistan government. These guardians would be asked to represent the Indus River in legal proceedings, enter into contracts on its behalf, and take other actions necessary to protect the basin. If implemented, these rights could prevent the construction of further dams on the river. Recognizing the rights of the Indus could shift the public perception of the river from property that can be partitioned to a relation with a life-giving partner. This shift could allow for the recovery of regional biodiversity and new collaborations between riverine communities. While it is important to understand the political, human rights, and economic dimensions of the 1947 Partition, it is equally vital to understand the way colonial legacies and the violent creation of nation states have impacted river systems and watersheds.