Community Recovery of a Watershed in Times of Perpetuated Conflict and Transition

February 19, 2019

This is a guest blog post by Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Environmental Humanities Kristina Lyons, on the public environmental humanities work that forms an integral part of her ethnographic practice. Dr. Lyons and Fundación ItarKa have recently been awarded a grant from the PPEH Teaching and Research Seed Fund to continue this work in 2019.

How might the reconstruction of the ecological or biocultural memory of war shift understandings and practices of truth, restitution, and justice? In what ways are rural communities that have been engulfed by years of social and armed conflict attempting to make peace with and from territories that have been the epicenters of violence?

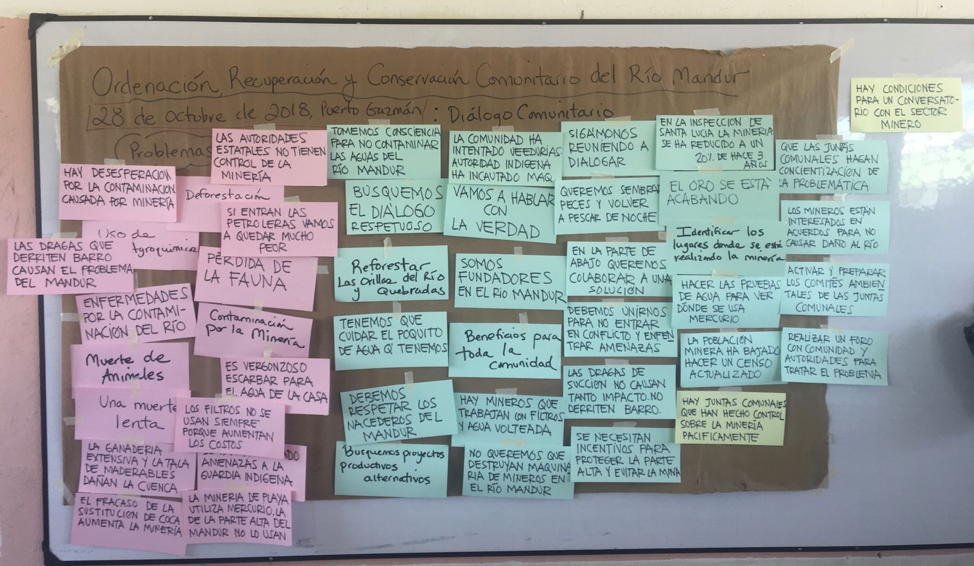

These are some of the concerns guiding a project on which I have begun to work on in the Colombian Amazon two years after a peace accord was signed between the national government and FARC-EP guerrillas to end over fifty years of war. This project in Puerto Guzman, Putumayo, developed in collaboration with non-profit environmental education and participatory research organization, Fundación ItarKa, intends to support the community governance, recovery, and conservation of the Mandur River watershed. The watershed is contaminated by illegal gold mining and has been impacted by heavy deforestation connected to the cultivation of illicit coca crops and intensified cattle ranching in the country’s western Amazon. These economic activities are tied to histories of colonization, internal displacement, poverty, narcotrafficking, and the presence of armed groups. War is never a human-only experienced phenomenon, and it is the rupture and tentative repair of socioecological relations or continuums of human and nonhuman life that is at stake as local communities imagine how to build a viable peace from war-torn territories. Inspired by popular movements that place “nature” at the core of Colombia’s transitional justice scenario, we ask how the reconstruction of the environmental memory of the Mandur River might contribute to community dialogues to resolve ongoing conflicts that have led to the degradation and continue to create obstacles for the recovery of the watershed.

Since March 2018, with Fundación ItarKa in Puerto Guzmán, we organized a series of workshops with rural communities that had never engaged in such a collective oral and written exercise. The workshops included drawing a timeline of important events in the memory of the community and engaging in a comparative diagnostic of the flora and fauna as remembered when residents first migrated or were born in the area, and the flora and fauna that currently exist. The act of collectively remembering the quantity of fish that used to inhabit the river, the number of wetlands and the quality of the water, the hectares of primary forest or the way trees lined and covered the riverbanks so thickly that they needed to be trimmed back to render the river navigable, opens up the possibility for the articulation of affective attachments that transcend understandings of the river as simply a “natural resource” or “water source.” People begin to share the reasons why they settled in the Mandur: fishing, bathing, mobility, beauty, paseos de olla, the cooler microclimates of the forested riverbanks, the wild animals they hunted and shared the territory with, and the access to water.

During the workshops, we invited downstream communities to imagine what would occur if the river’s course was inverse, flowing from the deforested Amazonian plains towards the forested Andean foothills. One of the conclusions that resulted is that there would be no water flowing at all. Another question that we posed to downstream residents is whether or not they consider repressive mechanisms to have been effective in dealing with their illicit coca crops. How had they felt living under the gun of the counternarcotic police over the past four decades? How would militarizing the territory, be it to end medium-scale mining livelihoods in the upper watershed or to curb their own deforestation downstream, in official times of peace be different than the criminalizing tactics of the War on Drugs?

These workshops created the conditions that enabled us to organize four community dialogues with social leaders of the upper, middle, and lower watershed to begin to analyze and pose community-based solutions to the degradation of the Mandur. We also collaborated with several artists to produce drawings of the environmental memories articulated in the workshops and to design pop up books for use as popular education materials in local schools and community centers. What might change if reconciliation and transitional justice processes attended to human and infrastructural loss as integrally bound up with the losses experienced by watersheds? How might affective attachments to the territories of rivers orient conflict resolution strategies between communities that continue to be mired in violence during official times of peace? What might reconciliation look like when the right to work (of miners, for example) appears to clash with the right to water of downstream communities?

These are some of the ethnographically informed questions that we aspire to address in the next stages of the project as we continue to accompany rural communities in the recovery and conservation of a heavily disputed and increasingly militarized watershed in Putumayo. We will continue this work in 2019 with the generous support of a PPEH Research and Teaching Seed Fund Award.