Explorations in Interpretation: Communicating the Entanglement of Science and Contemporary Life

March 27, 2019

Jesse Smith

Every week, like many other residents of Philadelphia, I sort the stuff I throw away. I separate plastic bottles, cardboard boxes, paper bags, aluminum cans and other recognizably “recyclables” from napkins, greasy pizza boxes, and other odds and ends generally recognized as “garbage.” Every Tuesday evening I take the recyclables outside in a blue plastic bin, and the garbage out in a white plastic bag, where they wait to be picked up by two different trucks from Philadelphia’s Streets Department.

Last week, like many other residents of Philadelphia, I also learned that the city has been burning half of the recyclable materials it collects. China, long the buyer of most of the United States’ recyclable materials, has stopped accepting its paper and plastic. Now those materials are being sent to landfills or, worse, incinerated in a process that releases dangerous chemicals and tends to disproportionately impact minority and poor communities.

This news came as a surprise in part because I had recently studied the history of plastic bottles as part of broader research on disposability in the United States in the 20th century. This was research for the Object Explorer, a new digital interactive experience I helped create for the museum at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia. This experience uses 3-D prints of familiar objects to prompt exploration of the materiality of contemporary life in the United States, such as the emergence of disposable goods. Users select an object to launch a deep dive into its history; its material nature; and its broader environmental, scientific, medical, and social dimensions — a mix that captures the interdisciplinary approach of the environmental humanities, broadly defined. For each object, the Object Explorer offers a text, video, historic photographs, patent images, advertisements, and illustrations.

The Object Explorer at the museum of the Science History Institute/J. Fusco for Visit Philadelphia

Some of the objects explored in the installation represent valuable developments for the environment and human health. The LED light bulb, for example, offers users the history of illumination by fire, electric incandescence and fluorescence, and more recent efforts to use semiconductors to produce brighter and more energy efficient light. It describes the particular challenge of producing white LED, which necessitated identifying the different semiconductors able to emit red, green, and blue lights that together make a white light. The syringe offers a history of the smallpox vaccine, as well as subsequent developments in germ theory and other preventative measures that have vastly reduced human mortality from infectious disease.

John Snow’s map of cholera deaths in an 1854 London outbreak/Wellcome Collection

A faucet invites users to explore the history of chlorination and broader developments in sanitation science such as sewage treatment and solid waste disposals.

An 1828 cartoon, "Monster soup commonly called Thames Water, being a correct representation of that precious stuff doled out to us!!!"/Wellcome Collection

Some of the included content on commercial material development speaks to broader historical trends and grim environmental futures. The plastic soda bottle tells the story of DuPont’s successful efforts to create a lightweight plastic strong enough to withstand the fizzy carbonated pressure of soda. But it also offers an opportunity to situate that story in a longer history of disposability that extends back to the turn-of-the-20th-century development of paper water cups and ends with current challenges to even the best recycling efforts: before China stopped accepting United States plastic bottles, the difficulty and expense of converting food and beverage packaging into safe new packaging meant most plastic bottles were “downcycled” into new consumer products such as detergent bottles and sleeping bag filling.

In my work on developing the content for the Object Explorer, I took pains to avoid reproducing celebratory ideas of science, technology, and material invention and innovation. The Pyrex measuring cup offers users a brief tour through the 2,000-year-history of glass, the late 1800s’ processes that improved the safety of laboratory glass, and the application of this glass for domestic goods. This object also reminds users of the significant continued use of such “old” materials as concrete, wood, and paper, as anyone who has passed a construction site or received a cardboard Amazon box would know (but might not reflect upon!).

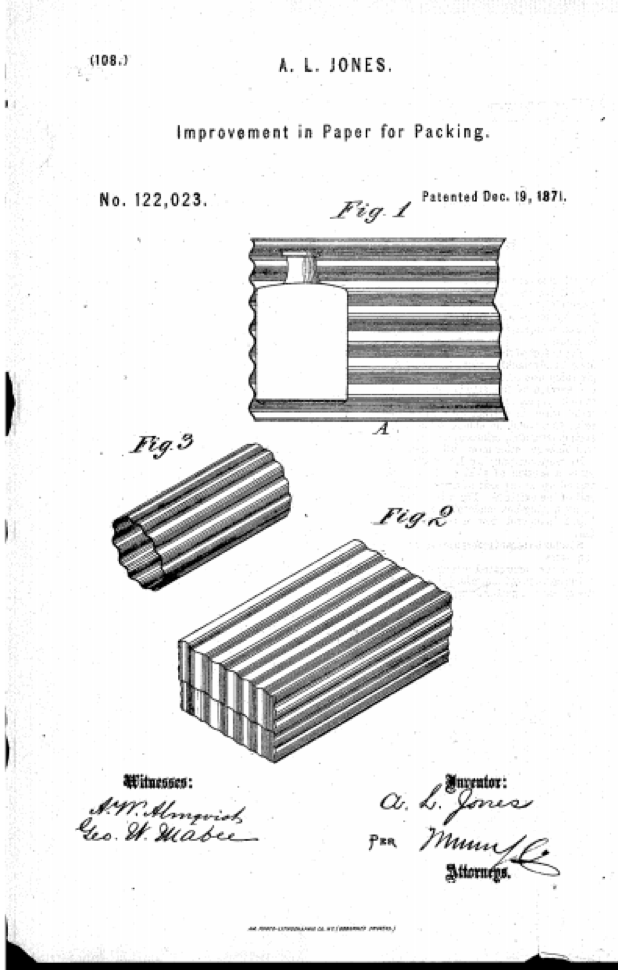

Albert Jones’ 1871 patent drawing for corrugated paper packing

Other content grapples with the mixed legacies of some materials: how asbestos saved some lives from fire even as took others through lung disease; how the soft quality of lead made it useful for increasing access to clean water in older homes, and how social and political factors exposed citizens, especially the poor, to these materials long after we understood their dangers. An ice cube tray offers a history of natural ice and mechanical refrigeration. It acknowledges the ozone-depleting quality of chloro-fluoro carbons (CFCs) such as freon, but also reveals how such refrigerants have improved U.S. consumers’ access to a wider variety and more dependable supply of nutritious foods.

Harvesting natural ice with an ice plow, ca. 1900-1906/Library of Congress

The challenge I faced as a content developer was to communicate to visitors not just the epistemological complexity of science — what do we know about the world, and how? — but also the ontological stuff it brings into the world and their myriad impacts (good, bad, and more often mixed). Teasing out those implications also reflected the trickiness of communicating the history of science to public audiences in ways that are neither wholly triumphalist nor entirely declensionist. In that way, this effort is a similar though more modest parallel to the Smithsonian Institute’s “Science in American Life” exhibit of the early 1990s. That exhibit portrayed science as a cultural and social practice, which in turn lead to criticism that its message was “anti-science, anti-technology”. Such questions about the character of science persist in the public realm, most visibly in debates over the quality, causes, and consequences of planetary climate change.

These are conceptual challenges that historians of the environment, science, and health will continue to face in the creation of public-facing work. This may be especially true in the environmental humanities, as we seek new forms of creative practice and expressive products to raise awareness of environmental dangers, convey the complex embeddedness and contingency of those challengers, and, perhaps most significant, nurture constant reflection on the processes by which we come to know them.

Jesse Smith is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History and Sociology of Science at the University of Pennsylvania with research interests in environmental history, the history of technology, and the material dimensions of consumer experiential products in the second half of the 20th century.