Mourning the Spokes-animal for Climate Change

July 11, 2018

The following post is part of the Exploring the Environments of Modernity series, featuring the voices of some of the organizers and participants of a symposium that explored the conceptual arenas of "environment" and "modernity" in the humanities and social sciences.

Mourning the Spokes-animal for Climate Change

Earlier this summer, the Gorilla Foundation announced the passing of their beloved Koko. Koko, a western lowland gorilla, made fame with her ability to communicate to humans through sign language. She knew approximately 2,000 words in the English language, learning 1,000+ signs in ASL throughout her 46-year-old life.

As I saw friends and family post articles about Koko’s passing – memorializing her death on social media – old videos of Koko also popped up, including a 2015 clip of the gorilla giving “a message for nations attending the COP21 Summit.” In the video, Koko signed that she was the spokesperson for nature and that man needed to “hurry,” address climate change seriously, and include the preservation of biodiversity in the Paris Agreement. She did so with the following signs:

I am Gorilla…I am flowers, animals…I am Nature. Man Koko love. Earth Koko love. But Man stupid… Stupid! Koko sorry… Koko cry. Time hurry! Fix Earth! Help Earth! Hurry! Protect Earth… Nature see you. Thank you.

There is no question that Koko was a special gorilla. She not only learned how to sign, but also how to play the recorder – demonstrating controlled breathing which was thought to be impossible for nonhuman primates. However, scientists debated Koko’s ability to understand the meanings behind her words and actions. A Snopes article addressing Koko’s COP21 video claims the film is incredibly misleading, partially because communicating basic needs and communicating ideas are two different frames of language. Not only was the video scripted and extensively edited after several takes, but Snopes pressed that the COP21 video was a classic case of anthropomorphism – or, the projection of human qualities onto other animals. The article cites biological anthropologist Barbara King to make this case - who wrote that the video “distorts who Koko really is; it conveys the wrong idea about signed languages; and it undercuts the seriousness of climate-change discussion.”

The debate surrounding Koko’s COP21 video reminded me of Dr. Supriya Nair’s astute exploration of the animal gaze from her presentation at the Environments of Modernity symposium. In her talk, Nair explored the multiple dimensions of human-animal interactions in film and literature – taking cues from the tiger in Life of Pi, the birds in Hitchcock’s The Birds, and the primates in Planet of the Apes to discuss how and when humans are rendered as animals, animals made human, and the moments when the boundary between the two collapses entirely. Using theorists Jacques Derrida and Judith Butler, Nair made the case that the animal gaze was the site of this confrontation – epitomized in iconic moments from these films and books, among others.

Quoting Derrida, Nair used her many examples to ask, “Is it when the animal looks at us when thinking begins?” When a tiger’s roar paralyzes us, or a bird’s silence is enough to terrify a human theater-going audience, what does this say about human domination? Nair noted that “it is not just the gaze that terrifies (sound is just as confrontational), and not only the human that dominates” in these episodes.

Nair also noted the end of <em>Life of Pi</em>, when Pi longs for a goodbye “look” or “gaze” from Richard Parker, which he is denied. <em>20th Century Fox.</em>

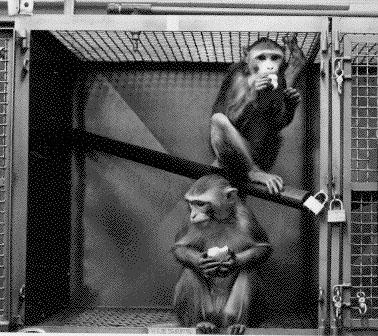

Related to Koko’s video, Nair’s talk addressed sites of “critical anthropomorphism;” moments when animals gaze (or make sounds or movements) at humans from places of vulnerability. “What do they see when they look at us,” Nair posited as she flashed images of experimental animals in cages. “Who are we who have done this to them?” Nair pointed out that anthropomorphism and anthropodenial were two sides of the same coin. Though there are moments when we, as humans, project our thoughts, emotions, and intentions onto other animals to achieve one goal (perhaps action against animal experimentation), there are just as many moments when we refuse human qualities in animals. For instance, it may be more difficult to use and consume animals if we accept their human qualities. Further, in both instances of anthropomorphism and anthropodenial, humans must refuse the animal characteristics within ourselves. This may keep us from recognizing the violence we perpetuate onto other humans, other animals, and other sites of nature.

Two primates in a laboratory cage – a similar image to those shown by Nair during her presentation. USDA digital reproduction from <em>Wikimedia</em>.

Koko’s case is a unique one in our propensity toward anthropomorphism and anthropodenial because she could communicate to humans through her sign language. While her gaze may have initiated thinking between the human and animal – in Derrida’s sense – her signing obliterated the human-animal boundary, which is often made and mediated by language. Her status as animal but ability to use human language was what made the COP21 video, regardless of its editing, that much more powerful to viewers.

Thinking with both Koko’s video and Nair’s presentation, it is important to consider the stakes in projecting and refusing human qualities on other animals. Each process maintains the human-animal boundary for a reason, and some of these reasons are quite legitimate. But we also need to recognize those moments – curated or not – when the nonhuman animal gazes at our actions. It may just be enough to disrupt everything we thought we knew about our place in the world.

Finally, when we mourn for and remember an animal like Koko, we actively recognize her and accept her human qualities. We may also accept and recognize our own animal characteristics, the line between the two collapsing not only through gazes but through scientific research which supports the fact that animals grieve and mourn in the same ways we do.