New Public Humanities Research at PPEH

September 17, 2019

Bethany Wiggin

Since PPEH started up, we’ve been trying and testing modes of public engagement, making “the effort to inhabit a difficult space of simultaneous critique and action,” as Deborah Bird Rose et al usefully defined the environmental humanities. Five years on, we continue cultivating that space, mindful of its thorns, rocks, and the occasional wily predator. It can be difficult for private R1 universities, such as Penn, to make room for public scholarship and teaching, across the arts and sciences, even with good intentions. Here’s some of the reasons why:

For faculty members, traditional metrics for tenure and promotion can seem to preclude the possibility of public engagement outside free time (which of course no one has). For students--and especially for undergraduates typically working with a professor only for the four fleeting months of a semester--it can feel impossible to engage with classroom issues beyond its walls; or, conversely, student activists’ concerns can feel miles distanced from the topics of the lecture hall. And, for potential public partners who might want to engage with faculty and students to develop community-based public research--whether through ethnographic fieldwork, oral history collection, community storytelling initiatives, and other social practice art projects--barriers to entry are legion, but include fundamental and profound differences in the time horizons for desired outcomes.

So how does PPEH navigate this terrain to make it more hospitable for faculty, students, and community partners? We’re continuing to grow living archives: publicly available digital collections of research materials, some also curated to create collections, exhibits, and digital and mobile tours. For our undergraduates, we have also created an increasing number of paid public research internships. In fall and spring, Grace Borroughs (C‘20) and Katelin Collier (C’22) conducted research for five episodes of the Data Remediations podcast, and soon began making appearances on the pod, one project in a bevy of digital and in-person storytelling engagements designed to bring environmental and climate data to life in a variety of narrative forms and media, culminating with a data storytelling festival in May 2020 (stay tuned for details). Grace and Katie are also back with PPEH this year to work on the pod; and they will also co-mentor (with a little help) an anticipated cohort of eight undergrad PPEH Public Research Interns.

Last year, PPEH consulted for the Humanities Action Lab (HAL), a consortium of forty colleges, universities, and community partners worldwide, and then we also signed on to contribute original public research materials to Climates of Inequality, a sprawling set of public engagement projects culminating in a traveling exhibit. This summer, our two new Public Research Interns, Lucy Corlett (C’20) and Jacob Hershman (C’20), created images and texts to capture the essence of PPEH’s ongoing community-based participatory research in Eastwick, a low-elevation and low-density neighborhood where residents love their trees and open spaces and bemoan rising waters in historic wetlands, home also of refining, airport, and highway infrastructure, two superfund sites, ongoing nuisance dumping, and of the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum.

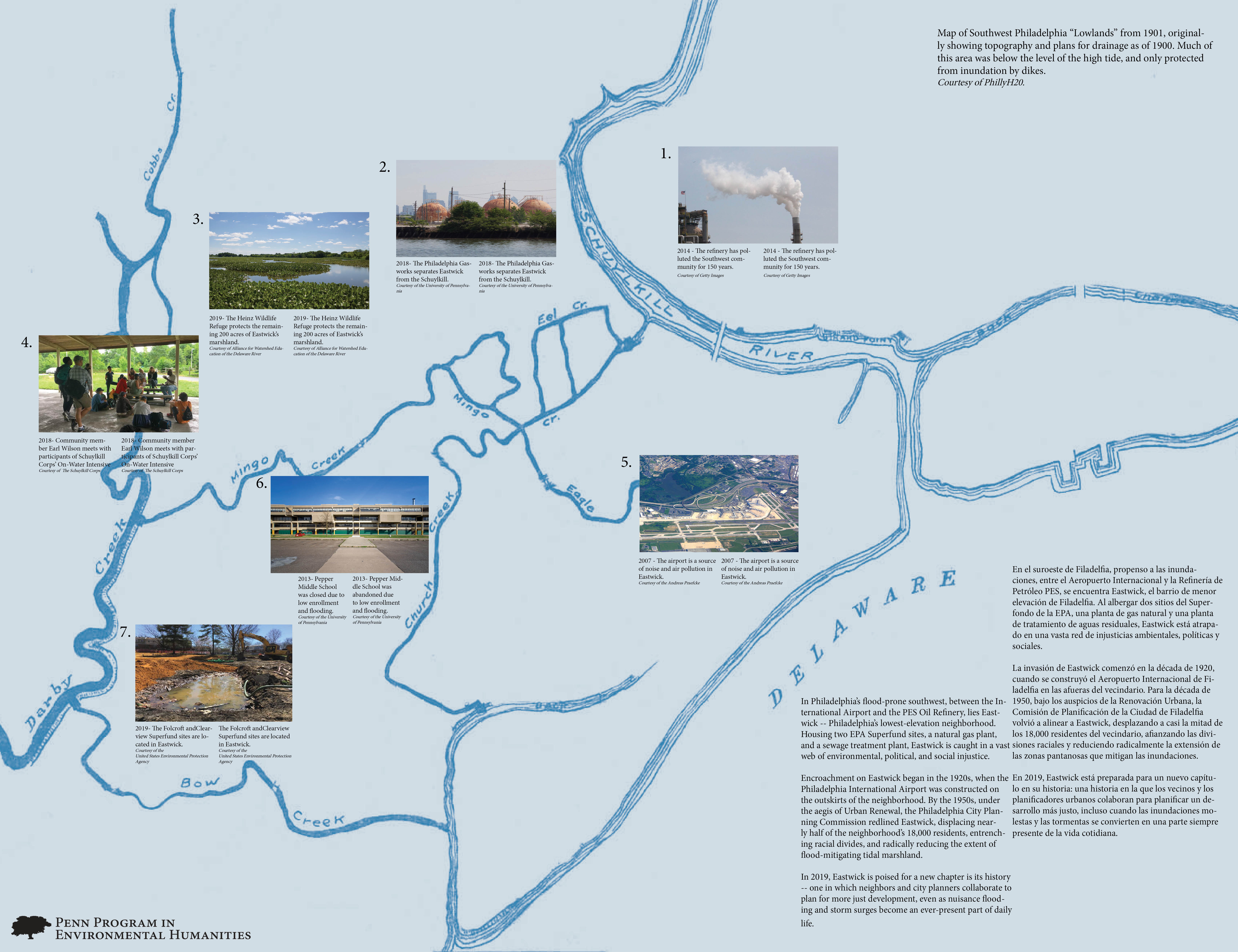

PPEH’s contributions to Climates of Inequality will receive a mandatory colorwash before they are exhibited. Here’s a pre-color wash sneak peek into their creation and a glimpse of how Lucy, Jacob, and I worked collaboratively to blend text and images of Eastwick amidst over a hundred years of wetland loss:

Photo 1: Climates of Inequality Exhibition Panel, Side A (with exhibit text not yet included with photo). Photo credit: Lucy Corlett, Jacob Hershman, and Bethany Wiggin.

Photo 2: Climates of Inequality Exhibition Panel, Side B. Original design and graphics by Lucy Corlett.

Lucy and Jacob also created extensive digital exhibits for our living Schuylkill River archive. Lucy, as she explains below, couldn’t stop thinking about Philadelphia’s decision to begin incinerating its recycling. Her research internship gave her room to explore waste and discard studies frameworks and to create a fascinating digital tour of the incineration plants which burn Philadelphia’s waste, included in our Schuylkill River archive. Please check it out! And watch as she develops it further in her senior thesis in Urban Studies. Jacob’s independent project acquainted him with energy humanities. Beyond the classroom or research lab, Jacob is the Campaign Coordinator of Fossil Free Penn, and the internship gave him the space to explore the histories and cultures of energy, especially oil. He began his project on Philadelphia’s oil refinery before it exploded in June 2019, as he explains. But the fire and the complex’s subsequent closure only cemented his resolve to explore how “in the winner’s circle of the global energy game, both oil and its casualties slip beneath what can be clearly represented or felt,” a sentence from Stephanie LeMenager’s Living Oil that Jacob takes as epigraph for his revelatory series of historical essays and thought experiments designed to help us see and otherwise feel the “petroleumscapes,” to use Carola Hein’s word, we make and are made by.

How could they burn our recycling?

Lucy Corlett

This question has been at the front of my mind since the winter of 2019, when I learned that the majority of recyclable materials collected in the city of Philadelphia were being burned at a waste incinerator in Chester, Pennsylvania. I found this revelation so terrifying that I decided to dedicate my summer as a PPEH Public Research Intern to researching Philadelphia’s relationship with incineration. My project focuses on this past year’s incineration controversy, with the first half chronicling the events (namely China’s recent ban on the importation of contaminated recyclables) that led to Philadelphia sending more than half of its collected municipal recycling to Covanta Delaware Valley, the largest waste incinerator in the country. The second half of my project discusses the technology and regulations that “control” incinerator emissions, the environmental implications of incineration, and the public health threats incinerators pose to residents in the Philadelphia area.

Unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately, I have resurfaced from my summer research with infinite questions and limited answers. I spent the majority of my time reading up on the history of Philadelphia’s reliance on waste incinerators, reaching out to the dozens of journalists who covered the incineration controversy this year, talking to experts and activists, and visiting incinerators with my fellow research intern, Jacob (that’s me at Covanta Plymouth Meeting, in the photo below). From all of that, I learned that the “incineration situation” is complicated and becoming more so every day. Some people see incinerators as a good alternative to landfilling. Some see them as viable sources of renewable energy. Most are horrified that recyclables would end up in a fire intended for other kinds of waste. Most importantly, the people who live in the shadows of these facilities have been fighting their presence for years. Extended exposure to incinerator emissions can lead to, among other things, increased asthma and cancer rates in adults and children.

It has become apparent that trash disposal and recycling aren’t just municipal challenges anymore. The global waste crisis is expanding at breakneck speed. Solutions are limited, and the ones available are usually financially unfeasible or actively threaten public health. But here in Philly, with the rollout of the Zero Waste and Litter Action Plan in 2017, there is hope that at some point in the future, mass waste incineration and the incineration of recyclables will be a practice of the past.

Check out Lucy's Exhibit in the Schuylkill Corps Archive, "Discovering Philadelphia's Waste Crisis"

Bearing Witness to Oil

Jacob Hershman

As a PPEH Summer Public Research Intern, I compiled a seven-part digital exhibit on the Philadelphia Energy Solutions complex (PES). Entitled “Witnessing Philadelphia’s Oilscape,” the exhibit provides a series of tools and techniques to comprehend the scale and scope of Philadelphia’s oil refinery. Until its closure in June 2019, it was the oldest oil refinery in the United States. (Incidentally, I decided to write about PES about two weeks before the explosion brought the refinery’s scale and impact to national attention.)

As I have come to realize, neither perception, nor intellectual contemplation, is enough to comprehend the primacy and ubiquity of oil. The magnitude of oil’s presence in industrial and postindustrial societies is too great to be sensed with those tools alone. In each of the seven sub-exhibitions comprising “Witnessing Philadelphia’s Oilscape,” I offer one method for what I have coined ‘bearing witness to oil.’ And by this I mean connecting visual, aural, and olfactory experience of the oil industry (pipelines, stills, stacks, oil-trains, etc.) with the complex systems of production, transportation, and consumption that those trappings support.

Ultimately, the digital exhibit catalogues my personal revelation to the oilscape, and so the information I present may not be as enlightening for all as it was for me. At the very least, I hope my work inspires others to find their own ways of witnessing some of the hidden complexities that pervade our complicated world.

Check out Jacob's Exhibit in the Schuylkill Corps Archive, "Witnessing Philadelphia's Oilscape"