Public Engagements, Part 4

April 10, 2018

What does is mean to do public research in the environmental humanities? This and other questions lie at the heart of this series of essays, "Public Engagements." Contributors, PPEH Fellows and students, reflect on: Who is the "public" in my public research? How will they be engaged? Does my project need a public audience? A participant audience? Participant observers? Am I looking for research subjects? Co-creators? How will I document my social practice research?

DATA BIOGRAPHIES

Alex Anderson, Comparative Literature & Literary Theory

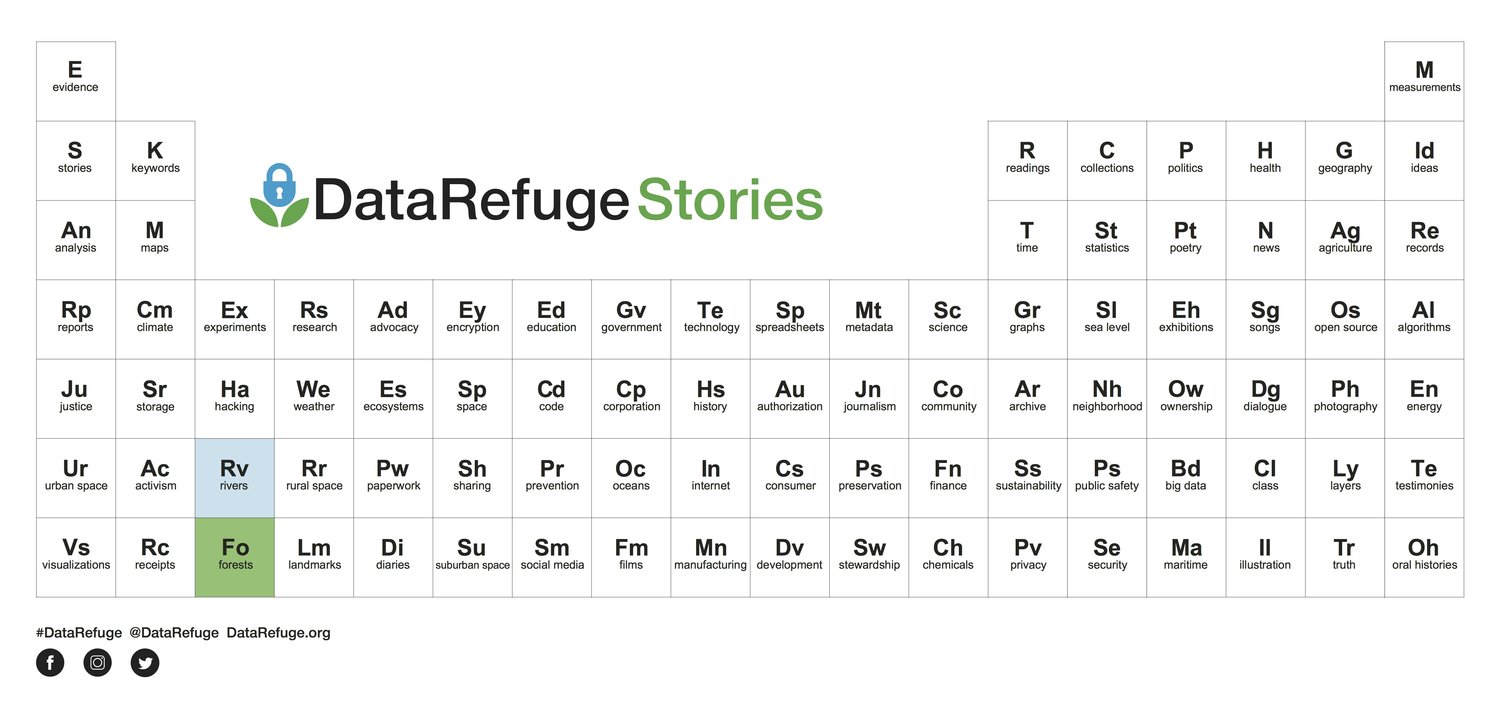

My ongoing work for Data Refuge Stories will involve the creation and dissemination of templates for “data biographies.” These long- and short-form stories will be used by researchers and city planners to tell how federal data is important in their lives and to their work. My sample biographies will be added to the larger Data Refuge toolkit as yet another example of how to engage publics in a playful, creative way. I hope that these models will also serve as inspiration for our journalism fellows when they attempt to narrativize data use in local communities.

The central challenge I’m facing is this: How can we give voice to such a nebulous concept as data and do it in such a way that it can be readily adapted by other data users with different datasets? My approach is to try to generalize the relationship between data and consumer by teasing out the data’s important characteristics. My templates will highlight the “liveliness” of data—which is to say, they will pay specific attention to the moments where data becomes active, whether that be in how it’s collected, how it’s interpreted, or how it moves downstream. This project not only traces the lifecycle but hones in on the social life of data.

The templates I will generate importantly have to balance content with voice. I am currently identifying different forms of life writing and adapting them to narrate the history not of a person or a place but of information. This is very much a speculative process: How can we give voice to inanimate data? Is it possible to do so in an engaging way? What narrative forms will allow us to bring into account the human actors on data? My work for PPEH will involve experimentation but will yield a product that rethinks biography in a creative, unexpected way.

FUTURE GUARDS

Carlos Price-Sanchez, English and Environmental Science

“We are all burnt by ultraviolet rays. We all contain water in about the same ratio as Earth does, and salt water in the same ratio that the oceans do. We are poems about the hyperobject Earth.”

So there I was, shivering in my skin-tight wetsuit like a shaved otter, rung in the ambience of my girlfriend’s menacingly chattering teeth, about to submerge my body into the waters of an Icelandic glacial lake. I had just spent the good part of an hour struggling to birth myself through the top of my wetsuit and spitting into the mask of my snorkeling gear upon the direction of the more veteran divers. “Not enough, More than that” my Russian co-diver said casually, informing me that the thickness of that saliva was the only thing going to keep my nostril breaths from freezing upon contact with the water and rendering me blind. Effectively neutralizing any potential for awe-inspiring epiphanies.

Entering the water the first two things you realize are that it’s actually warmer than the air you were just standing in and that the lake isn’t as deep as you thought it would be. What you thought would be a vast abyss droning down to the basement of the earth is often only as tall as a robust deer fence, and at some sections just a few inches from your torso. You might, at this point, think the view from the parking lot was better than this- recalling how you stepped out of your car to a visual buffet of pristine desolation, long flat expanses with peaks erupting like new teeth into a yawning firmament of sky. This is the kind of existential sci-fi landscape that would make Frankenstien’s heart throb.

After my eyes adjusted to their new environment though, I began to notice the arrows of light tunneling in smooth cylindrical beams, falling steadily to the bottom as if they were hot eggs dropped into a plumb of fresh snow. My body was so easily buoyant that kicking was unnecessary. I let my body relax into the slight current - hovering facedown and astronaut-like above the remnants of a roiling crack of earth, the recently loosed granite blocks beneath me remaining still , brooding with a precarious energy akin to fresh coals.

Witnessing this I became suddenly conscious of the fact that everything I was seeing was simultaneously new and exceptionally old. What was being communicated to me was a geological brail, an intimate, face-face encounter with the private and lifeless cathedral brought about by the same geological shifting that had fractured continents. I felt myself participating in a ritual acknowledgement from one geological actant to another.

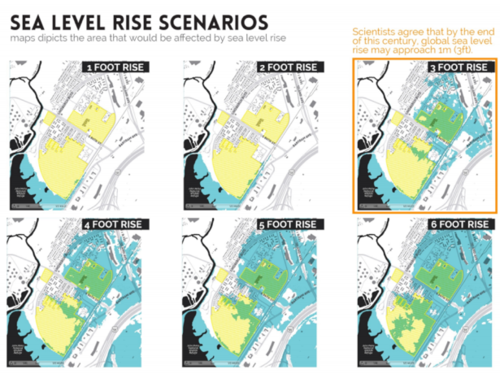

Riding back home, after my pow-wow with these drowned rocks, I began to reconsider my poetic work on the community of Eastwick - a community, much like the Icelandic landscape, of active geological change. Eastwick is a community just outside of Philadelphia that has been built upon the historical filling of ancient buried streambeds and marshland. The result of this poor construction is that the, predominantly lower-income, homes of the area are actively sinking into the ground as that filling erodes and floods - cracking the earth and the structures above it. The area, besides its active sinking, exists at an increasing risk for flooding due to sea level rise and weather changes. Before my trip to Iceland I had been conducting a poetic-journalistic mapping of the stream beds beneath Eastwick - hoping to explore the ways in which the poetic-landscape of the page helped to demonstrate how our interactions with suppressed ancient landscape disseminate today into problems of socio economic segregation and environmental disaster. (Take a breath after that one.).

Upon revisiting this work, I became frustrated with what I felt was a troublesome and insidious shortcoming of certain environmental art discourse of aesthetically separating itself from interacting physically with the publicly social, economic and environmental conditions of its production. The reality was, my art was in no way approaching the physical acknowledgement-ritual achieved through spit-covered goggles in a trench often no deeper than the height of your average pro-basketball player. The fact that so much art, including my own writing, ostensibly was addressing our climate reality through social critique and meaning-making, yet remained materially separated from any form of implementation, struck me as a failure of that art to adapt to the age of the Anthropocene. If we as human beings have come to be geological actants on a global scale, then our cultures, our social identities, and our creative expressions and thinking must also aim to manifest themselves physically in order to simultaneous narrativize and combat our negative effects on the planet.

As of now I aim to take the enactment of my writing off the page and onto the landscape of its creation. By taking fragments of my and others works I hope to create placard sites of ritual-turning structures of waste production, water transportation, urban development, streams, cafes and schools, into sites of poetic-remembrance through the simple pasting of makeshift historical plaques. Though I think to many it has become clear the array of repercussions playing out across a range of temporal scales and the expressly ecological need for appropriate cultural a frames for understanding and narrativizing these calamities, we must continue to adapt our modes of doing so. Could a superimposition of narrative to our physical spaces help us to both acknowledge and ritualize our built environments as well as materialize our ecological languages? Who knows. And yet, babbling into the face of geology, may we do our best to act as future guards.

DOWN/STREAM

Fiona Jensen-Hitch, Anthropology and English

How can people understand where their water comes from, and where their water goes to? The act of turning on a faucet, drinking from a glass, flushing the toilet; these are all actions which have become automatic, require little thinking from those doing them. Yet, at the same time, we live in a world where public concern with climate change is ever-escalating, and one concern is water: both too much and not enough. Yet, these concerns over rising and falling waters often remain vague, far away from the doorsteps and faucets of most. I am interested in this disconnect, which seems to be part of a larger narrative around climate change as existing largely outside a personal, immediate narrative for those that it does not most visibly affect.

There have been many projects aiming bring the Anthropocene into everyone’s home, so to speak, and so this is by no means the first project to attempt this. Rather, I envision that my project will contribute to and become a part of this work, continuing the conversation. Specifically, I wish to travel to resources of water within and around the Philadelphia area, to build a sound and image archive of these locations. These materials will then be paired with the places which they either send water to or receive water from. For example, what would it look and sound like to have a recording of the Schuylkill River playing in a public bathroom? As it travels to different sites, this project may also live as a digital archive on a website. Certain installations may be interpreted and enacted in performance, either by myself, another individual, or a group. In this way, I hope to publicly push people to think about the cycle of the water that they use, and the disconnect that remains between environment and humanity.