Reading Buildings Like Documents with Joy Huntington

November 17, 2022

An interview with ACLS Leading Edge Fellow Joy Huntington, appointed to Historic Germantown for the project "Decolonizing Historic Germantown: Re-Framing Sites, Collections, Landscapes, and Museums," a collaboration with PPEH. Huntington speaks to Mia D'Avanza about her research into Germantown's early 20th century history as a site of Black businesses and culture using 1913's "A Souvenir of Germantown" booklet.

Mia D'Avanza: Joy, could you talk a little bit about what led you to focus on historic Germantown as a site for examining colonialism and how that shaped the history there, and what it means to decolonize historic Germantown?

Joy Huntington: I think it was the call for the fellowship [an ACLS Fellowship that Historic Germantown hosted in collaboration with PPEH Program Director, Bethany Wiggin] to begin with, but my dissertation and field work that I've done here in Madison, Wisconsin has always been focused on those populations, those people that we don't hear from. I talked with my mentor, who was the co-chair of my dissertation committee. She specialized in vernacular architecture and after taking her classes and with her influence I realized that I belong within this field. And it was because it looked at buildings and people that are often overlooked. We did not esteem them enough to preserve their writings–all we had left were the houses. I started digging into those houses, and began to read buildings as if they were a document. That was my way into finally uncovering these mysteries of these people. I took the perspective that these unknown and overlooked people were really the people that maintain society and push forward progress.

My dissertation was focused on women and looking at, particularly those women in some cases that weren't in the spotlight, but who were [making changes while] living their lives within the spaces that the culture and society readily gave to them. Looking back we would say that wasn't much of a life, but they still made something very lasting. And I think, because we tend to look at the past from our own perspective we miss the great things that they did. So that's what I did for my dissertation and am doing now: I am looking at historic Germantown, which has a very clear storytelling tradition centered on these very wealthy European immigrants who you could say tried to tame the land and tame the people. It fits right into what I do. There's a lot of the story and about people that we're not telling, and their voices should be heard. I never called it decolonization, I just called it history, which is funny.

I just find those stories more fascinating. I've been using the Souvenir of Germantown document a lot lately, investigating the places that are better identified in there and trying to find more of the stories of the buildings, people, and the culture that they pushed forward. It's been exciting.

J. Gordon Baugh Jr., A Souvenir of Germantown Issued during the Fiftieth Anniversary of the

Emancipation Proclamation at Philadelphia, PA, September 1913 (Philadelphia: Baugh Press, 1913).

MD: It seems like you're kind of like a sleuth.

JH: Trying to find out who these people are and where you can go [with that]... I enjoy that process. I think we've always had a culture here in the US of only looking at the headliners.

MD: I guess that’s intentional, right, who gets to be a headliner, who gets to be remembered. You said something that really struck me, which is “reading a building like it's a document.” Can you talk about how you learn to do that?

JH: I think it all starts with the prevailing canon of architecture and style. To date the building you go into looking at it through a material culture lens, of construction, so looking and seeing, “Oh, what kind of joinery or nails they use, were the heights consistent throughout the space? Where were the doors at?” So in an older house that had doors that separated between the public spaces, and the workspaces, you can start to think “Okay, they might have had servants. Or slaves. Especially if there's two different doors. And then, if you went upstairs to the attic and saw how that was situated and organized, you can detect if there was a live-in servant or slave, and what their accommodations were compared to the family.

You can also begin to tell when a building had additions made and the materials that changed with that, lik the type of flooring. So all that starts to come into place. There was a house, it was a prominent house in the Potomac area…I can't remember the name of it right now, but it was restored and it basically had three wings, you could say.

And one was the servants or slave wing, because it was slaves before it was servants, and you can see the different heights of where the servants and slaves lived, and the space that they had. You could say “Okay, I know they slept here, and then, as time moved on, on this opposite wing, the heights of the rooms were different from that first one.”

MD: Do you mean the ceilings were lower?

JH: The ceilings were lower where the slaves and the servants lived further back. I see it ultimately became storage, but it was over the kitchen too.

MD: So that's hot, above the kitchen. It starts to tell a story.

JH: A story of why they were kept in that area, and then the staircase to the back, there was a staircase to go upstairs so that they could clean and never have to go into the main area to be seen as many times. And the materials of the floors and the walls were different, and the insulation was also different, so you're starting to get these ideas of their place in society: their value, the value of their work, and how they maneuvered throughout that space to do their tasks, their job, their duties or whatnot. By the owners not wanting to have their servants or slaves seen, you can see how they use the building to hide them, but also keep them close.

MD: When you're looking at Germantown, are you looking at houses that primarily would have belonged to wealthy people or are there a lot of buildings that are still extant that would have housed working class people?

JH: There's not a lot of working class buildings. From the early 1900s there have been worker neighborhoods, little sections, and they're called “fill-ins”. They were built as plots of land began to be divided, when factories came in and the workers were being situated closer to the factories. They would also be less desirable places because of the pollution and the noise [from the factory]. Many of those have been torn down because of decay, because they weren't built as well. Some still remain, usually because somebody's still living there.

But because I'm using the Souvenir of Germantown booklet, most of what I'm looking at are the more prominent places because that’s what was depicted. I mean no matter what race or ethnicity you're looking at, each group is going to put forth what they consider the most important.

Emancipation Proclamation at Philadelphia, PA, September 1913 (Philadelphia: Baugh Press, 1913).

MD: Can you talk a little bit about Souvenir of Germantown, why it was created, when, by who?

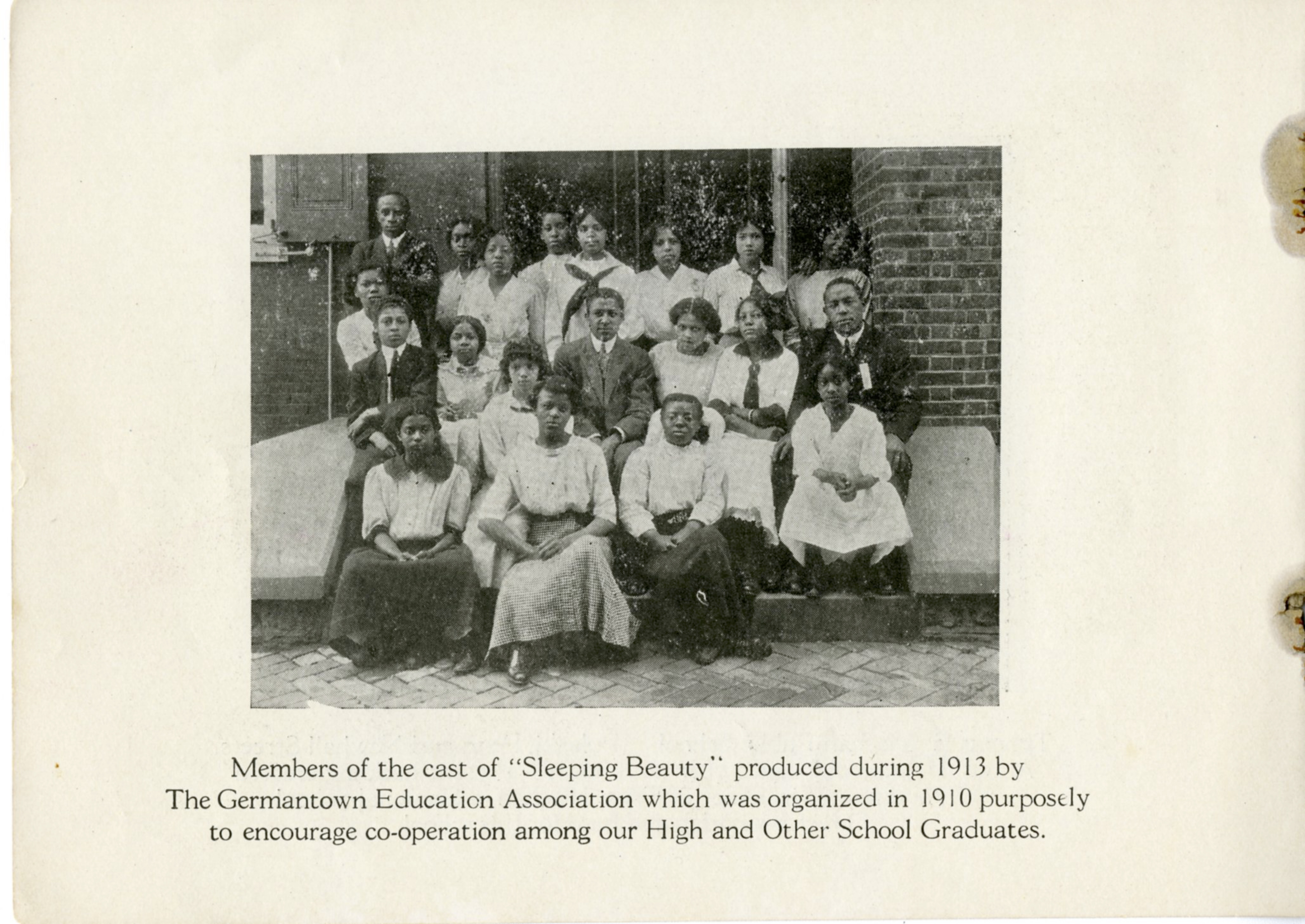

JH: It was published by an African-American owned publishing company, Baugh Press, in 1913. It came out not that long after the Germantown Historical Society published their own kind of city tourist booklet. Of course it didn't include any of the Black places or businesses so Souvenir of Germantown was kind of like, from my understanding, an answer to that. It identifies some doctors, a lot of churches, two or three schools, some after school program groups and some businesses.

Churches are great because, for me, the number of churches that they have there really tells a story about the rootedness of the church and faith in God within that community. And those have very clear names, very clear locations in Souvenir.

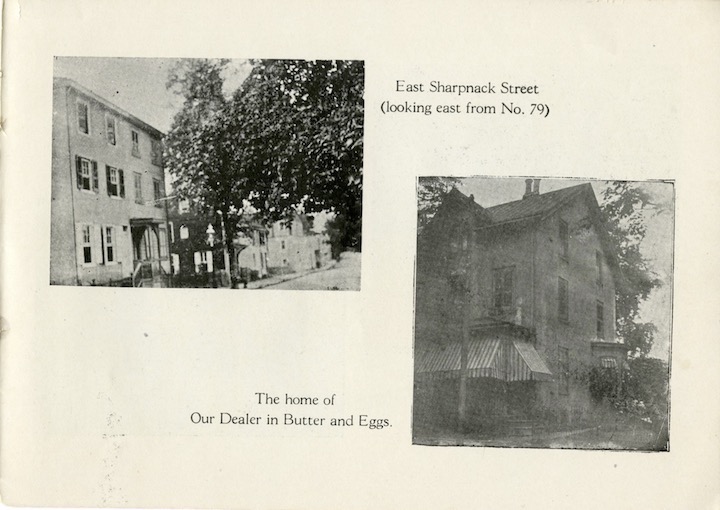

Now, when we started getting to some of the other places… the doctors [offices], they had names. Many of them had addresses, and the schools had their names, some little details, but not a lot of detail. With the businesses, it was interesting because it would say “Our Barbershop”, “Our Antique Store”, so now that's the last part that I've been trying to find information on, and digging for, to find first what these businesses are actually called, then their locations; I have some generalities of what street and things of that sort, but it wasn't as fully-fledged as what the Germantown Historical Society had published.

But it's a start and I think it is worthwhile to examine, and what I've enjoyed doing is just building on top of this Black-owned family publishing company’s work, and honoring that work so that we know where it comes from, and why it was done, but in also expounding on some of these people and places and making connections to our present.

J. Gordon Baugh Jr., A Souvenir of Germantown Issued during the Fiftieth Anniversary of the

Emancipation Proclamation at Philadelphia, PA, September 1913 (Philadelphia: Baugh Press, 1913).

Right now it is just the past that I'm working with, but we're hoping to connect it and add a little bit more contemporary places, like a business and schools. There's one doctor that I started out with, William Warrick, and part of my research discovered that in his family his sister was a famous sculptor who did a lot of Harlem Renaissance artwork and African artwork. Dr. Warrick was a doctor living in Germantown and he died, I believe, in the 1960s and he was involved in the community. This doctor advocated for the Joseph E. Hill public school to be renovated. He partnered up with one of the reverends of the local churches and they petitioned the school board to do extensive renovations on the Joseph E. Hill school. So that's adding faith to his social capital as a doctor. To garner the amount of signatures he needed, he had to know people and he had to be involved more than just popping up here and there.

MD: I wonder if you could talk a little bit about how the history of Germantown is sort of framed and remembered today. I know that there is a legacy of colonial revivalism (“an effort to look back to the Federal and Georgian architecture of America's founding period for design inspiration.”) there. Could you kind of expand on that a little bit for people who maybe haven't been to Germantown or or don't know why colonial revivalism is the legacy that's been handed down about it.

JH: I think, from my perspective, there's been so much attention on George Washington and the battle of Germantown. I believe that's where a lot of it is rooted, in one aspect. And that is what the Germantown Historical Society, and before that, what was called Site and Relic Society, really kind of held on to to showcase their relevance and their significance in the founding and development of this country. Do I blame them? No.

Germantown was the seat of the early American republic for two summers and that’s a crowning jewel of its history. Going back through some of the early publishings of the Site and Relic Society, you see some of these early settlers of Germantown talking about how they needed to compete with Boston in Plymouth. They felt, “Why shouldn't we be at the same level as them, if not better? We have the same importance and significance within the Union.” And I think that's another aspect of why this colonial revivalism is a huge part–because they were competing with New England and staking their claim also on the founding of the United States. And so you have that other aspect, so that tourist book that was initially published was part of that plan.

MD: And when was this taking place, primarily?

JH: Before 1920, and that struck a chord with me because these people who were writing were people who had been there, are parts of families that had been early settlers and it was an opportunity for them to have their family remembered. So, I think it's a multi-layered answer that is easy to overlook and it's not just one thing, but it's family pride, of being one of the first settlers.

So colonialism is one aspect, but when I look at colonial revivalism, it's “Let's go back to that and the way that we think it is, it was” or–one thing I've learned through material culture is that we borrow from folklorists, and one thing that you always have to be careful of is the romantic dissipation of stories. I've used oral history in my practice too and people can romanticize, especially if it's an oral history, and the telling of stories over generations a little bit gets added here a little bit gets that it there. So it wasn't always intentional.

MD: And in this work, do you feel like the Souvenir is your storyteller?

JH: I think, yes. I haven't been able to verify all the places [in the Souvenir] but I've been able to verify quite a number, and then add in a lot of information through newspapers, archives, and those sorts of things and just kind of have fun with it.

This is only the starting point. And I think, as I create, recreate, and add to this almost exhibit that it's going to become, there's always more you never capture and a perspective that you're missing. I think it's exciting when somebody has been overlooked even though they're long gone. To say that they mattered even when they're gone, I still think it's important. And the way you can do that for somebody who has passed on is to give them a name. That is something that I can do, especially with this project for that time period, I can at least begin to do that.

This interview was edited for style and clarity.