Research Residences, Part 3

May 3, 2018

WASTE STREAMS AND ARCHITECTURAL DREAMS

Ayodh Kamath, PPEH Graduate Fellow and Doctoral Student, Architecture

Observing trash on the sidewalks, sifting through it, and taking what might be of use to me in building sculptural bridges at Bartram’s Garden made me see trash as being ‘public material’ – a resource available to those who choose to use it, much like the better understood notion of public space.

Snippets of conversations with people that I had while collecting trash were indicative of the different relationships that people have to trash. One person – a handyman with a property management company – looking at me pick up a table leg, said, “A man after my own heart! This stuff is like free IKEA.”

Other reactions were not so positive and included uncharitable judgements muttered and derisive glances. Sometimes these looks were covert, and at other times I faced openly hostile stares. These reactions from people explained the suspicious, monosyllabic responses to the questions I put to others trash collectors I encountered. While I was collecting trash for ‘academic research,’ they were seemingly doing it out of economic necessity.

While opinions among people I encountered were polarized, hours of research online and in the library have yielded no definitive answer on the legality of scavenging trash from the curb. So I carry on doing it, as do others. As long as trash picking does not directly harm or inconvenience anyone, it seems to be tolerated.

I encountered a similar ambiguity in what I can and cannot be do at Bartram’s Garden, where I am planning to locate the trash sculptures I make. In a long meeting I had with Danielle Redden, the River Programs Manager at Bartram’s Garden, she explained to me that jurisdiction over the garden overlapped between the John Bartram Association that manages the space, the Schuylkill River Development Corporation and Philadelphia Parks and Recreation. While all these entities exercise differing levels of control over the garden, none appear to have the resources or incentives to control the activities of people in this space as long as it does not interfere with the activities of others – both human and nonhuman – who use the space.

This engagement with individuals and institutions, and reading about the tensions between private enterprise and civic bodies makes me wonder, somewhat cynically, if that which enters the public realm is simply what is not amenable to commodification. And once something can be commodified – be it public land or metals in the trash – its ownership becomes private.

PUBLIC HEALTH AND COMMUNITY WELLNESS: ARE WE LISTENING? OR WHO IS LEADING?

Xelba Gutierrez, Master's Candidate, Environmental Studies, Concentration in Environmental Justice

I have been working with the Lillian Marrero Branch of the Free Library which is nestled in Fairhill, a Black and Latino community of North Philadelphia, and a place marked by structural racism and poverty. I’ve been supporting the library with the new Healthy Communities Initiative, an amazing and ambitious effort funded by the City of Philadelphia’s Department of Public Health (PDPH). The initiative wants to increase awareness of community health and wellness resources while increasing the perception of the library as one of those resources. The Initiative also hopes to elevate stories and voices of this community and their health, highlighting how the community works against the challenges of various forms of repression. My research project has been to create and implement a public engagement strategy for the Healthy Communities Initiative.

During this residency, I have been able to observe the relationships and interactions between library staff and the public they serve. And, I was also able to contextualize and appreciate the library as the space where the Healthy Communities initiatives will take place. Conversely, the product of the community engagement should inform the library of community needs and will hopefully open avenues for collaboration between community members and the library.

The engagement process started as an effort from the stakeholders to signal a genuine commitment to build trust within the community and to help the longevity, sustainability and public support of the initiative. But as I learned, bringing together grassroots work and institutional work is often a challenging exercise. As Robert Chambers points out, often in institutional efforts of community development: "What is measurable and measured then becomes what is real.” This experience helped me understand that a great task for public engagement work is to avoid the pitfall of doing work for the community and instead work with the community. For this to be more than just a theoretical concept, we need to intentionally and closely listen to them and our efforts need to be led by the community we are trying to affect.

Works Cited: Chambers, R. R. (1995). Poverty and livelihoods: Whose reality counts?, p. 181.

GIVING A VOICE TO DATA

Alex Anderson, PPEH Undergraduate Fellow, Comparative Literature & Literary Theory

My research residency has been a challenging if ultimately rewarding experience. I say this because it took a while to articulate my public engagement project—though I always knew it would be centered around “data biographies”—and even longer to figure out how my project would align with the larger goals of Data Refuge Stories. As we were gearing up for the semester way back in January I took it upon myself to try a little bit of everything. For several weeks I worked with the “Data Mad Libs” forms collected at the American Geophysical Union conference and used them to populate our online storybank. Seeing how respondents chose to fill in the blanks gave me an initial sense of people’s affective relationship with their data. I took this knowledge and next worked to create a survey for researchers and other professional data users.

This second step served (in hindsight) as a period of trial and error. I based the survey on one originally circulated during our Data Rescue events in the fall of 2016. What I didn’t realize until perhaps too late was respondents’ willingness to actually sit down and answer our overly complex questions. And so this was put on the back burner. Maybe one of the biggest takeaways here was that with intellectual work—and with public-facing work especially—it is key one knows the audience he or she is addressing. This insight very much shaped my approach as I began to think about the deliverables (forthcoming in the DRS toolkit) for my research residency. How exactly could we prompt data users to tell the life story of their data? Not only that: How would my storytelling tool fit in among the existing suite of tools? My residency helped in answering these questions because at Data Refuge I received constant feedback from colleagues and was allowed to try out imperfect options along the way. It was this room for exploration and experimentation that ultimately helped me figure out how to give voice to data.

WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR MAINTAINING SAFE DRINKING WATER?

Wenjun Gao, Masters Student, Social Policy and Practice

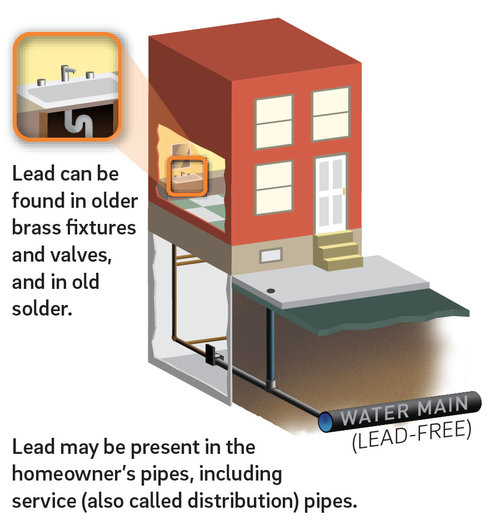

I aim to use Philadelphia Water Department (PWD)’s 2015-2017 lead testing sampling as one of the foundation materials of my research project. It is difficult to find out the specific information about testing samples’ geographic and socioeconomic information, what motivated them to participate as volunteers and how much do they trust the test results. The staff that I am in contact with from the PWD has agreed to provide their testing program’s data. My goal during my potential research residency with the Water Department is to find out more information about where the testing program participants lived and whether these areas overlap with the risky living areas in Philadelphia.

My meeting with the PWD public educational director was very productive and eased many concerns of my, but at the same time raised more questions relating to how can PWD and the city government together use their collected data to ensure everyone to have safe drinking water? I have learned that the PWD has been changing their policies regarding help residents to replace lead pipes, but does every Philly resident know that? The post-meeting session of self-reflection reminds me that none of the PWD’s lead testing participants questionnaires ask about socioeconomic status, but I learned from research that low-income status has a clear connection with worse home quality and therefore less safe drinking water possibly.

In my following onsite visits, I would like to ask one of the questionnaire design staff about the design logic. I will also ask PWD that how is data used by different departments in the local government and how do they integrate data into policy making procedure? As my research goes further and I recognize the demand for more transparent data, instead of spreading out my focus with more questions, I intend for my residency to help support me in answering the original research question – how shall we trust the safe water quality in Philadelphia?

ME, THE TRUTH AND THE BARTRAM GARDEN: HOW THE ARCHIVE CHANGED MY RIVER

Luna Sarti, PPEH Fellow, Doctoral Student in Italian Studies

As a person formed in literary studies in Italy, I received little training in thinking about the general public. While I have always had an idealistic striving for the ‘common good’, concepts like ‘community engagement’ or ‘place-specific research’ never figured in my internal debates. Thus, in my life before PPEH, the word ‘archive’ would simply evoke a pool of documents that historians and philologists would magically use to extract clean, readable histories. In short, my field was aesthetics and my duty was to engage in interpreting exceptional texts. A well-known solitary triangle: me, the text and Truth.

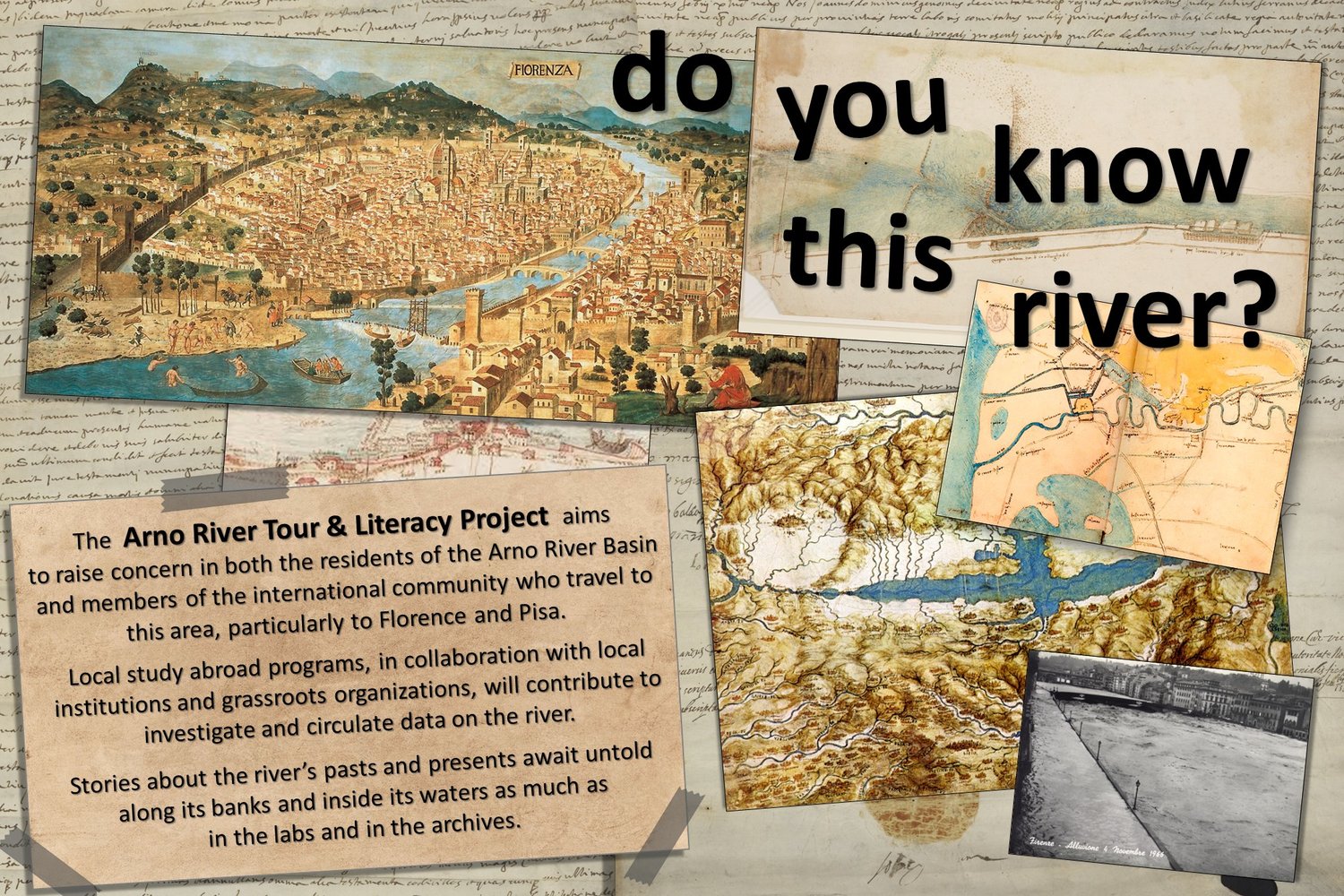

As a PPEH fellow, thanks to the encounter with researchers and research from other disciplines, I had the opportunity to engage with different methods, theories and practices. Lately, spending time at Bartram Garden archive pushed me to reflect on the incredible affective potential that archives can have, when accessible and open. Following this experience, archives will feature in my future research and projects on the Arno river not simply as conglomerates of messy data, but as anthropological spaces that can engage people in their own way. My aim is to re-activate knowledge of all the different Arno rivers which have existed and whose stories lie untold along the banks and in the waters as much as in the archives. My project around the forgotten manipulation of Tuscan water has evolved thanks to this experience.

As a person who used to be indifferent to archives, I learned to appreciate the unexpected potential of the material interactions archives enhance. Although aesthetics still holds its grip on me, I have come to view representations as complex repositories of common knowledge. Bartram Gardens and the curator Joel Fry have taught me the generative power of attunement. This is what I hope to disseminate by taking people to Tuscan archives. In a time of accelerated life speed, archives oblige us to pause, to take a chance and to suspend the need for fast profit research.