Research Residencies, Part 2

May 2, 2018

Throughout the course of the spring semester, PPEH Fellows and students enrolled in our "Public Environmental Humanities" course engaged local partners in short-term research residencies with local environmental organizations, public humanities projects, and municipal/civic entities. In this blog series, fellows and students reflect on the following prompt: “How has your research residency shaped your own research project?”

STORYTELLING DATA

Seung-Hyun Chung, Undergraduate PPEH Fellow, English

As a playwright, I imagined absurdist plot scenarios when I thought about a story that could merge environmental/climate data with theatrical storytelling. Boulder-like datasets falling from the sky; or a vending machine in an apocalyptic world that dispenses data! These were interesting thoughts, but they were still rooted to a traditional narrative-arc storytelling that I felt lacked the public engagement crucial to Data Refuge. I wanted to write a story that was more relational and more importantly, curated people’s interaction with their data.

My data’s name is

My data

My data

Is

People.

Me.

The Pacific Ocean.

My data is

Volatile.

It lives in the ocean,

Somewhere I can’t imagine.

Not Quantifiable.

Well, it's not like my data is dead, but you know.

It’s complicated.

My data and I are: on the same wavelength!

We're done. But we are still friends. I think.

But are we?

Maybe.

Above is a sample text of a performance/poetry project I am now working on through my research residency with Data Refuge. My current project attempts to copy/paste/juxtapose/edit existing responses from the data storytelling toolkits (Data madlibs, data Valentine) into a dramatic performance text. While I do add some of my own creative transitions and dialogues, I mostly curate a story from the verbatim words that people have written to describe their data.

Working with Data Refuge has kept me asking the following questions constantly: What is data? What can data be and become? Who uses and creates data? How are we livingdata? To tell stories about data requires us to shift our own perceptions of data as not some detached, lifeless object of information, but as a vulnerable and permeable body living within us. My mode of storytelling must also shift with this perception -- not rooted in just myself as creator, but a story co-produced, enacted, and legibilized as a collective.

My residency at Bartram’s Garden to research methods and materials for a Tour of a Schuylkill River Past (to 1756)has revealed a challenge of timescales. While BG operates on a schedule of the changing seasons, Penn marches to a rigid academic calendar. This mismatch has become a learning opportunity.

TOURING THE RIVER AND THE GARDEN

Samuel Sanders, PPEH Undergraduate Fellow, German Languages and Literatures

Since the Garden shuts down its outdoor community-oriented programming in the winter and early spring, completing my research (to find out the needs and wishes of potential tour participants, as well as to learn from the Garden’s staff, who have experience creating tours of the Schuylkill) by the end of March has been impossible. I won’t be onsite at the Garden until the last week of coursework at Penn, so I have had to find a different angle for beginning my project.

I have been front-loading inside research on historical documents while waiting for warmer weather and the opportunity to to talk to community-members and potential tour-takers at the Garden. The academic research will thus be subject to change--subject to the real-life, on-the-ground experience in place and on its time.

As I transition into summer, I look forward to continued opportunities to conduct research and learn from experts along, and on, the Schuylkill River while being a PPEH Summer Fellow and a participant in the Schuylkill River Research Corp June On-Water Intensive.

"PRIDESBURG"

Emma Singer, Undergraduate PPEH Fellow, Urban Studies

No river runs straight (sans some parts of the LA River but we won’t even go there). Similarly, research projects -- mine in particular -- seem to constantly revolt against linearity.

I first encountered the Riverfront North Partnership(RNP) back when it was called the Delaware River City Corporation[1] and I was exclusively studying bike infrastructure (it was Heraclitus who said, there is nothing permanent except change[2]). I returned to RNP for my research residency with a plan to focus on how the organization was reconnecting Northeastern neighborhoods to the Delaware River.

After a dizzyingly terrifying bike ride that included a brief stretch on an I-95 off-ramp, I arrived at the RNP headquarters, located along Delaware Avenue just North of the Philadelphia Port (recently rebranded ~PhilaPort~[3]). The RNP staff were exceedingly generous with their time and provided a full overview of the organization as I munched on Peanut Chews (s/o for corporate sponsorships that involve candy). They told me how the organization had been conceived in the mid-1990s by a former Congressman who wanted to “bring people back to the river”. Despite bumps and a rebrand, the organizations has continued to accumulate funding, support, and power in the Northeast.

Northeast Philadelphia feels like another world. Composed of dilapidated industrial buildings, multiple charter schools, tidy streets, and a surprising number of well-kempt stray cats,[4] it’s geographically near Fishtown and yet a world away (i.e not yet overrun by yuppies in beanies). While my tour of the RNPs 11-mile stretch of greenways and parks stretched multiple neighborhoods, Bridesburg, the most eastern community and the first we visited, called out to me as a place with a story to tell.

Described by RNP staff member as “Pridesburg” (for its insatiable neighborhood pride), it’s a mostly white, conservative neighborhood in Northeast Philly. During my time there it was referred to many times as “Old School”.[5] Still, there is diversity in this working class neighborhood, which also claims a long history of immigration: of Germans in the mid-18th century and eventually (in the 1890s) the Poles, who remain well-established.

Bridesburg also has an enduring relationship to the Delaware River as an important port and historical site. Early 20th-century photos show Bridesburg residents enjoying the Delaware as a site of recreation: racing boats, swimming, and even -- one frigid winter -- ice skating. Ironically though, Bridesburg’s industries both contributed to its economic success and its loss of the river as a valuable recreation space. In their brief history of Northeast Philadelphia, Harry Silcox and Frank Hollingsworth depict the large industrial oil spills that, whether intentionally or accidentally, killed most aquatic life in the Delaware and made it unswimmable by the 1930s.[6]

The research component of my residency has so far involved a lot of listening, a crucial step to entering any new neighborhood.[7] Eventually though, I hope to turn the sounds I’m hearing into recorded audio and package it all into a podcast-eque form. These sounds will include, but may not be limited to: RNP’s Earth Day Event, oral histories of the river from current Bridesburg residents, and the sounds of the water itself.

While not a sentient entity, the Delaware has provided joy, heartbreak, and now, perhaps, hope. Through my research project I plan to pick up the story of Bridesburg, its residents, and river at a time when RNP is trying to reconnect to a past that few of the residents were alive to see.

[1] (Somewhat) Interestingly, the organization is named for a “River City” development that never was.

[2] Also Heraclitus: No man ever ever steps in the same river twice.

[3] It seems snazzy branding efforts are the key to getting people excited about water orgs.

[4] Also gated communities, a public mansion, a prison, a yacht club, an almost abandoned nursing home complex, hundred of recalled VW cars, and a shocking number of brownsites.

[5] Possible a stand-in for ‘racist’, confederate flags generally being a good indicator.

[6] Even more pessimistic historians, cite the pollution of the Delaware as far back as 1769 when visitors commented on the “mess” of the river and Ben Franklin, so disgusted by the water quality, left money in his will for a public Philadelphia well. https://journals.psu.edu/phj/article/viewFile/59953/59771

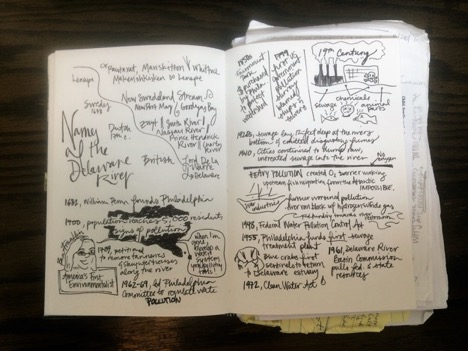

[7] I’ve bolstered my knowledge by reading ironically dry (harhar) Delaware River histories. As a way to entertain myself while reading and increase the likelihood that I’ll look back at my notes, I tend to “cartoonize” the textual data; pulling out important quotes and words and sketching when words aren’t enough (Photo 1.1).

A LESSON IN PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT

Hanna Morris, Doctoral Student, Annenberg

Federal censorship of climate research and data is on the rise in the United States. Reports by the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative (EDGI) and Columbia’s Silencing Science Tracker, for example, illustrate the ongoing obfuscation and removal of climate change from governmental reports and websites. Climate change is already popularly imagined as a “distant” and “far-off” phenomenon (i.e. polar bears, melting glaciers, doomsday apocalyptic scenarios), and so efforts to remove educational material, citations, and links to climate datasets further distances and obscures the present, physical reality of climate change. In light of this growing threat of censorship, public engagement and education on a local, situated scale is becoming more and more important.

Awareness of the proximity, presence, and relevance of climate change in everyday life is essential. Climate change needs to be visualized and understood as a material and physical reality of daily life as opposed to a distant and obscure abstraction. Artistic and civic interventions are therefore essential for invoking this awareness and for disrupting governmental attempts to limit public access and understanding of climate data and science.

On March 24, 2018—I traveled to the New Museum in NYC with Data Refuge team members Carlos Price-Sanchez and Alex Anderson to lead a workshop on how to do just this. We asked participants at the National Forum on Ethics and Archiving the Web to think carefully and critically about public engagement. Through our workshop, we introduced the Data Refuge toolkit and opened up a collaborative dialogue about public storytelling techniques. We worked with participants to think about best methods and practices for making environmental data more personable and relatable. And we concluded with a productive call to action asking: how can we tell the story of climate data?

Moving forward, I will continue to think through the question: How can we invoke recognition of climate change in everyday life? From the Data Refuge workshop I co-led, it became very clear that cross-disciplinary partnership is essential. In order to resist federal censorship and climate denial, we need to engage and motivate civic care. And this must begin on a local and personal level.