Soggy Cities, Entry 3: New York

July 1, 2019

Martin Premoli

In this entry, Nicki Pombier Berger (Founding Editor, Underwater New York) explores how various writers and artists are responding to New York City's shifting edges. This is the third entry in the Soggy City Series, edited by Martin Premoli.

On Once and Future Water in New York, City of Islands

New York is a city of islands, with approximately 520 miles of coastline. Many of these miles were once wetlands and are projected to return to the water as some iteration we may not yet have a name for. What is a place that was? Sunk is too sudden, though Sandy showed us it’s possible here, that velocity of loss. Submerged suggests the water did it, dunked the edge’s head and held it there, under. Is it under, place, still there like some Atlantis, to be visited as myth or dream, waiting, wavering in its new dim light? Gone, perhaps, is cleanest, but what kind of word is that for all that’s lost?

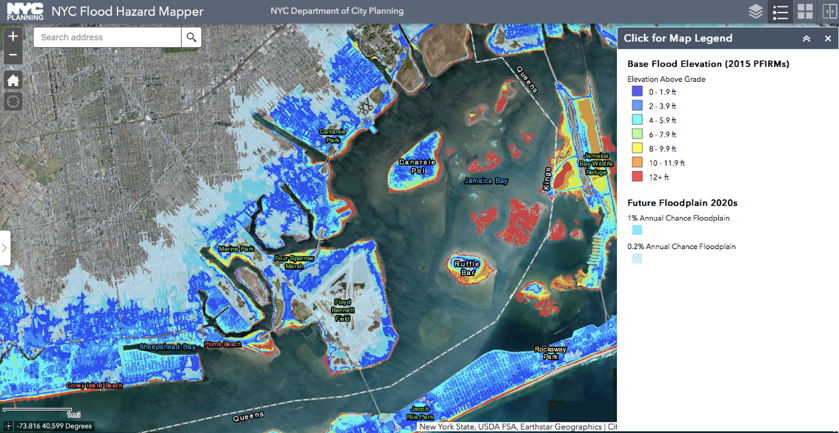

We stand to lose a lot, if predictive maps like this one from the New York City Department of Planning Flood Hazard Mapper bear out. This screenshot shows the future floodplains of the southwestern coastlines of Brooklyn in the 2020s. Just look at all that blue.

Screenshot from NYC Flood Hazard Mapper

This is not a map predicting the imminent contraction of the city’s edge; all this land will not, in the next decade, vanish into the sea, gone. What this map does is shade the odds of who will face annual flooding, and how much. In a city as densely populated as New York, these swaths of blue show innumerable future losses of the uncountable intimacies that connect a person to place.

When Hurricane Sandy hit in October of 2012, residents of Sheepshead Bay on Brooklyn’s southern shore were ordered to evacuate. Some did, including John and Sally, who share their story in this short film by Charis Emily Shafer.

Screenshot from “Submerged,” by Charis Emily Shafer

John is a “clandestine painter,” Sally his muse. He was working on landscapes — not portraits — of Sally, who had recently been wracked with pneumonia, fragile, at life’s edge. When the waters rose, filling their basement, all his paintings were lost. Gone. He knows his is a personal tragedy; he knows from one house to the next, the tragedy is different. Interviewed in May 2013, he says can see it in his neighborhood, in his neighbors — it’s “pneumonia of the block,” the flood is “right there on their faces.” One neighbor said to him: who knows, you can do something good out of this. That’s what art is about, he says, finding order out of chaos, making beauty out of ugliness.

This point on the line of his story was pinned down eight months in, post-Sandy. In the years since, there has been a dramatic real estate boom in Sheepshead Bay, notwithstanding the storm surge residents like John and Sally survived, nor the predictive blue on the flood hazard map above.

The edges defining our city of islands have never been fixed, have always been fluid. They have been hardened to house us, expanded with landfill, as with where I write from, Governors Island, whose southern hundred acres were created in the early twentieth century from earth excavated for the 4/5/6 subway lines that run an artery up Manhattan’s east side. Is this cannibalistic self-invention characteristic of the city? Do we bury and gloss the cost of growth? Nothing about the landscape here on the southern cone of Governors Island suggests that it wasn’t; that what it is, is a fiction insisted into existence.

View of Manhattan from “The Hills,” a new park developed on Governors Island’s southern acreage. Photo © Robin Michals, 2018

The construction of an edge is, in a way, the telling of a story: you are here. But a story doesn’t start when you enter it, or end when you leave. We are here, at a tenuous, invented edge, on once and future water. What can we do?

One thing to do is look hard, and one “we” doing the looking is a community of artists and writers making work on the shifting edges of New York City. For the past ten years, Underwater New York has prompted and published creative work inspired by the waterways of New York City. Though our name suggests otherwise, we aren’t apocalyptic (or predictive) — we began when an article by Chris Bonanos, published in New York Magazine, listed some twenty objects found beneath the waters around New York City — a giraffe skeleton in the New York Harbor, a Formica dinette upright at the bottom of the East River, a reef made of Good Humor ice cream trucks. These seemed perfect prompts for writers of fiction, which we founders of Underwater New York were. If the work of fiction can be to resuscitate, claim or reclaim by way of invention, what might happen if we grab this cast-off effluvia and wonder: what was or is or might this be, or what might it say, given words? And so began our love affair with the landscape of the city’s sixth borough, its waterways; all they hold, all they hide, all they shift and shape.

Dead Horse Bay, photo © Adrian Kinloch

There’s a way in which the origins of our project pattern the city’s way with things: dredge it up and reshape it, transform trash to form. One of the sites that has most inspired creative work for our project this past decade is Dead Horse Bay, once Barren Island, whose story rides precisely this Mobius.

Screenshot from the home page of a Facebook group for descendants of Barren Island

Dead Horse Bay is on the same southern shore as Sheepshead Bay where John and Sally live, a few miles east along the coast, marking the mouth of Jamaica Bay. Nearby, other low-lying neighborhoods — Gerritsen Beach, Marine Park, and, across the strait, the long finger of the Rockaways — were flooded by Sandy and stand to see more of the blue on that map in the decades to come.

Dead Horse Bay is quiet, uninhabited but for a few park rangers who live on the grounds in what is now Floyd Bennett Field. Artists, collectors, and urban explorers are drawn there today by the trash that washes ashore or is revealed at low tide. Once a large island at the western edge of the wetlands of Jamaica Bay, Barren Island became mainland in the 1920s, the salt marshes packed to land with nearly eight hundred acres of landfill. Atlantis inverse, from island to land. Barren Island was filled in to pave way for Floyd Bennett Field, the city’s original commercial airport, named for the aviator whose claim to have piloted the first flight over the North Pole has been disputed since it was made. Contemporaneous critics said he’d simply flown out of sight, in circles. Another line a possible fiction, a wish enshrined in name.

Before erased to mainland, the roughly hundred acres of Barren Island was a world apart, by geography and then by design. Two thirds salt marsh, much of the island was submerged each spring, leaving thirty or so upland acres, forested with cedars, edged with beach, home in the early 1800s to an inn for sportsmen and fishers and three or four families. In the mid-nineteenth century, Barren Island caught the eyes of a certain strand of industrialist: brokers in offal, at peak some twelve or so competing factories that transformed the trash of the masses into their own private empires on the backs of black laborers and immigrants from Poland, Italy, and Ireland. In a 2000 piece by Kirk Johnson in the New York Times, descendants of these workers remembered a rural, seaside life a world apart from the immigrant experience of the tenements of the Lower East Side, the streets of New York whose refuse came daily in overfull stows to be sorted, rendered, processed into someone else’s profit. On Barren Island there was fishing and crabbing, each family with a cottage, and weeklong wedding potlucks, a tavern where Mooney Zemzizsky atonally pounded the keys, accompanied by his brother on clarinet. There was diphtheria and they were whisky raids, a legend of pirate silver, melees and mysteries, a runaway blimp. There was the time in 1909 when a dozen “sanitary police” from the mainland took up arms against 500 wild hogs who were herded to rescue by the resident immigrant women. There were workers’ strikes and shipwrecks, saloon fights and fur bans, and in 1905, unusually high tides, wind, and “an unknown factor” caused a landslide, and half the eastern end of Barren Island slid back to sea, taking a two-story warehouse with it. Two years later, two more buildings and a pier were washed away as the island was once again cleaved by the sea.

These were lesser headlines about Barren Island, which was most known for the intense stench attendant to the industry of taking in and rendering the five boroughs’ daily animal dead. Mainlanders organized an “Anti-Barren Island League” in the 1890s, complaining of not only the smells but the leakage into Jamaica Bay of greasy industrial residues that clung to their boats, killed fish, poisoned oysters and clams. The Anti-Barren Island League in some ways formalized into political language the municipal posture toward the people who lived on the island and labored over the city’s trash. Barren Island had no public water supply, no sewage system, no fire department, no hospital. One lone boat ferried residents to and from Canarsie twice daily, and when the bay froze over, they lived off their own livestock and homemade bologna.

At its peak, Barren Island was the capital of the world trade in white gold, “artificial guano,” the conversion of dead animals to fertilizer, glycerin and other chemical products. Native Americans were using bird droppings as fertilizer as early as the second century BC, but an American glut for guano, especially among Long Island farmers who needed to feed a growing New York City, took hold in tandem with American expansionism in the 1840s. An island off the coast of Peru was the world’s prime source for guano, and when Peruvian bird dung that had accumulated over centuries was exhausted or diplomatically inaccessible, American agricultural entrepreneurs sought to transform urban waste into synthetic fertilizer instead. As chemists found ways to make waste profitable, the longstanding New York City tradition of ocean dumping became seen as its own kind of waste: a waste of would-be profit. Barren Island, remote enough to house the dirty business of grinding bone and boiling flesh and blood, yet easily accessible by boat, at the western edge of the Jamaica Bay wetlands, became home and hub to this capitalist alchemy, converting the city’s masses of slaughterhouse waste, carriage horse carcasses, and butchers’ offal to proverbial gold.

With the advent of World War I, the demand for byproducts of this process spiked, and as new technology developed and the organizing efforts of the Brooklyn mainlanders against the Barren Island “nuisance” wore on, a competing rendering plant opened on Staten Island. The industry on Barren Island began to wane, and factories began to close. After World War I ended, and with it, demand, the future of this industry was uncertain, and without the clear line to profit, the process was mired in city politics. At this point, it was clear that there was no land in city limits remote enough to neutrally contend with the waste we generated; everywhere, there were complaints. But as one former New York sanitation commissioner said, “Unlike polluted air and fouled water, which can be talked about endlessly, garbage must be put somewhere.” From 1918 to 1925, New York City began dumping its trash in the ocean once again.

What happened to Barren Island? Factories closed. People continued to live there, wanting the garbage — their livelihood — back. The wetlands were packed in with landfill, trash magicked to land. Floyd Bennett Field opened to great fanfare and quickly faded, too far away from the heart of the city to sustain commercial flight. In 1936, Robert Moses evicted the last remaining families from the community still called Barren Island, which went from a misnomer to the name we now know it for: Dead Horse Bay. Today we park near Aviator, a commercial recreational center banked on either side by abandoned hangars, and walk across the rush of Flatbush Avenue, Brooklyn’s own urban highway, to an unmarked trailhead, and wander through the weave of sea oats up and over a dune, to a view each time I see I say: This, too, is New York City.

Dead Horse Bay, image © Adrian Kinloch

Since 2009, we have been bringing artists of all stripes to this invented place, to reinvent it, themselves. I myself have written of it, in my 2015 short story, “Cold,” for an event at Winter Shack, a temporary exhibition space on mainland Brooklyn. Dead Horse Bay is still known for its trash, transformed now not to cash but to appeal to the curious. The coastline is littered at low tide with a gumbo of the last century’s junk — bottles, linoleum, leather shoes, tampon applicators, stray toys, ceramics, brand-stamped bricks, tires, wires, fishing line, bristled old toothbrushes, whistles, chipped off bits of dishware. Fossilized newspapers, headlines thumbed by time, illegible. Headless dolls, bodyless doll heads, and this, our mascot, a pink kangamouse, missing one ear, gazing to sea, its lightbulb heart unbeating all these years.

Kangamouse, Dead Horse Bay, photo © Adrian Kinloch

Poet Matthea Harvey wrote a poem for Kangamouse, excerpted below, that reads like an emblem for our project, for this place: what will remain, when it’s slid fully back to the sea? What will our names say of us? What, at this tenuous, invented edge, can we say of this land, and, perhaps most crucially, who will have a say?

Perhaps Kangamouse

has something to do with their mysterious notion of “Play”—

a type of waiting for sunset that involved throwing

spheres and grimacing. He may well be yet another

Withholder, since when we press on his button,

like all the other Gods we’ve found and abandoned,

nothing happens. Night makes light we murmur, and look

up at the sky with the face the Last Ones called Hope.

References / Further Reading:

- UNDERWATER NEW YORK

- SILENT BEACHES, UNTOLD STORIES: New York City’s Forgotten Waterfronts, by Elizabeth Albert and Underwater New York

- FAT OF THE LAND: Garbage of New York the Last Two Hundred Years, by Benjamin Miller

- THE OTHER ISLANDS OF NEW YORK: A History and a Guide, by Sharon Seitz and Stuart Miller

- New York City Department of City Planning, Flood Hazard Mapper

- “Kangamouse,” by Matthea Harvey

- “Submerged,” by Charis Emily Shafer

- “Cold,” by Nicki Pombier Berger

- “All the Dead Horses, Next Door: Bittersweet Memories of the City’s Island of Garbage,” by Kirk Johnson

- “What Do You Do With the Garbage? New York City’s Progressive Era Sanitary Reforms and Their Impact on the Waste Management Infrastructure in Jamaica Bay,” by Kevin Olsen

- “Transformation on Brooklyn’s Southern Shore,” by Ross Barkin

- “Secrets of the Deep,” by Chris Bonanos

- Photos by Adrian Kinloch and Robin Michals