Understanding Environmental Injustice Through The Philadelphia Tribune Archive

June 15, 2021

The Spring semester has drawn to a close, and Summer is in full swing. What better time to take advantage of academia's seasonally slower pace and the opportunities for reflection it offers? In this post, Georgia Ray, a former PPEH Public Research Intern (2020-21) and recent Penn graduate, revisits her work as a research assistant with Professor Jared Farmer.

Georgia says, "As a part of a broader project aiming to catalog the history of fossil fuel in Philadelphia, this semester I worked alongside another research assistant, Mikayla Golub, and Professor Jared Farmer to understand the impact and relationship between Philadelphia’s Black community and the area’s fossil fuel industry. Focusing on the city’s historically Black newspaper—The Philadelphia Tribune—we uncovered themes of environmental racism, community outreach, unexplained pollution, refinery fires, and protests going back to 1901. Most recently, a 2020 article in the New York Times documented the long-lasting health effects that living near the PES refinery had on Philadelphia’s (primarily) Black residents."

Read about their findings below.

I decided to join this team after taking Professor Farmer’s class in Fall 2020. Called “Petrosylvania: Reckoning with Fossil Fuel”, the class delivered on its promise — it showed us the good, bad, and ugly of the fossil fuel industry and allowed us the space to make up our own minds about what that means for the world, the future, and the state. After that foundational learning, we also all took on a research project in the class. I focused on connections between University of Pennsylvania trustees and the fossil fuel industry. When Professor Farmer mentioned he would like someone to stay on into the next semester to continue researching, I jumped at the opportunity. I knew it would be a great way to see another side of this same issue. So from studying mainly white men and their connections with the industry, I shifted my focus and began to look into how the Black community was affected in the same time period.

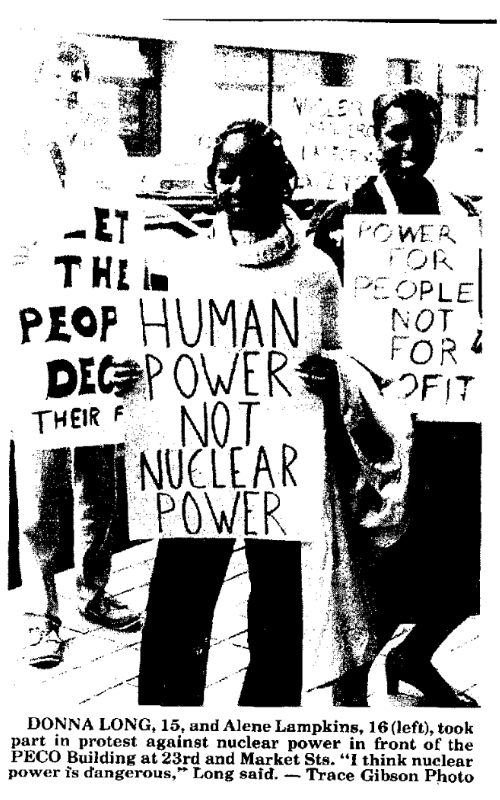

Image from The Philadelphia Tribune; published in 1979

Working with Professor Farmer and Mikayla on this project was a fantastic experience. Mikayla and I knew each other previously from Bloomers, a sketch comedy troupe where we served together as business managers. Having this small team where all three of us knew each other pretty well led to a space for innovation, creativity, and exploration. Mikayla and I bounced ideas off each other while Professor Farmer imparted wisdom and tricks of the trade. We were able to discover so much more than I ever expected and Mikayla is continuing on with the project even after I graduate.

Many may have some insight into the relationship between the Black community and fossil fuels in Philadelphia based on a well-read 2020 New York Times article. However, this is not the first time a newspaper talked about the harms of pollution from refineries for those living nearby. In fact, in 1956, The Philadelphia Tribune published an article entitled “Air Pollution Not Modern” which discussed the historically bad air quality in the city dating back to 50 years prior. In the article they highlighted “industrial gas” and promoted the usage of scrubbers. Unfortunately, while the 1950s saw a jumpstart of the conversation surrounding pollution, it did not see the end of fossil fuel related contamination in the city. In 1964, the Congress of Racial Equality picketed Sun Oil because the company did not take pollution and police brutality seriously, both of which primarily affected the Black community. In 1969, the city proposed stricter emissions standards, met by protests of support from those that wanted cleaner air in the city.

The 1980s and 1990s saw the popularization of terminology like “environmental racism” and one provocative Tribune headline called toxic waste the “New Back of the Bus for Blacks”. In 1981, a promised refinery tax fell through the cracks, inciting backlash from the Black community. The 1990s saw a burgeoning of asthma among the Black community in Philadelphia and a debate as to the cause.

Battles between the Black community and the fossil fuel industry were not only confined to arenas of health and pollution. In 1961, Sun Oil became one of many high profile companies subject to Black ministers’ Selective Patronage program. These ministers encouraged their congregants to withhold business from certain corporations until they ceded to the ministers’ demands for fair, Black employment. This patronage program even gained the attention of Jackie Robinson, who penned an op-ed of support in The Philadelphia Tribune.

Headline from The Philadelphia Tribune; published in 1963

Other instances of racism in the fossil fuel industry are documented by several discrimination suits (primarily against PECO and Sun Oil), including one from a former PECO employee who was emboldened to file after hearing a PECO executive use the n-word at the company’s long-standing Black History Month celebration. In 2001, another backlash against racism was launched when Christine Todd Whitman was slated to head the EPA. Black community members were worried that, because of her history of racism, she would not effectively protect their interests and work against environmental racism.

Over the years, there were also attempts at positive relations from the fossil fuel industry with the Black community. There were a number of career fairs hosted by fossil fuel leaders in local high schools, a popular cooking school held by Philadelphia Gas Works in the 1930s, and various charity initiatives ranging from sending Black children to summer camp to helping clean up a Black community’s block. However, pollution and racism from the fossil fuel industry has stuck in the collective memory of the city, more so than surface level gestures towards community.

Georgia Ray is a former PPEH Public Research Intern (2020-21) and Penn graduate, C'21. At Penn she triple majored in Cognitive Science, Philosophy, and Urban Studies with a minor in Environmental Studies. Georgia will be working for the Environmental Law Institute in DC come August as a research associate. She is originally from Denver, Colorado.