Writing Stories Into the Garden: Researching Francis Pastorius’ Colonial Garden with an Archaeobotanist and Historian

February 5, 2021

Gardens and farms in North America were and remain practical endeavors, but if we look closely at Native American gardens and colonial American gardening and farming we can see that many people believed plants to be divine beings that had the power to heal and nourish. They made gardens and wrote stories about plants according to these beliefs. One such gardener was Francis D. Pastorius (d. 1719), who lived in Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood.

In this Field Note, Miranda Mote, a fifth year PhD candidate at Penn in the Weitzman School of Design and Chantel White, archaeobotanist at the Penn Museum, discuss how they came to collaborate on research into Pastorius’ garden, the subject of Miranda’s dissertation.

This is the first entry in a series of three, edited by Mia D’Avanza. Parts two and three will be posted in the coming weeks.

Miranda Mote: Before I came to Penn, I worked as a licensed architect. I had a very practical education. I returned to school to study the history of landscapes (gardens and farms) and when I started at Penn, because I had no education in plant science, I knew that I needed to work with anthropologists and botanists to supplement my research.

One of the areas that I felt very deficient was botany and science in general, so one of the first classes I took at Penn was in the anthropology department, “Plants and Society”. I have always been very much interested in how people interact with plants, and how plants, in essence, interact with people. Gardens are one of those places where that relationship is amplified. The subject of my dissertation was an early American garden. I had lots of written documentation of the specifics of the garden, the plants and the material of the garden, but I needed to translate the gardener’s 17th-century vocabulary about plants and gardening in order to reconstruct the garden. I met Chantel by taking that [Anthropology] class and we collaborated together on a couple of occasions throughout my research. So that's who I am and how I met Chantel.

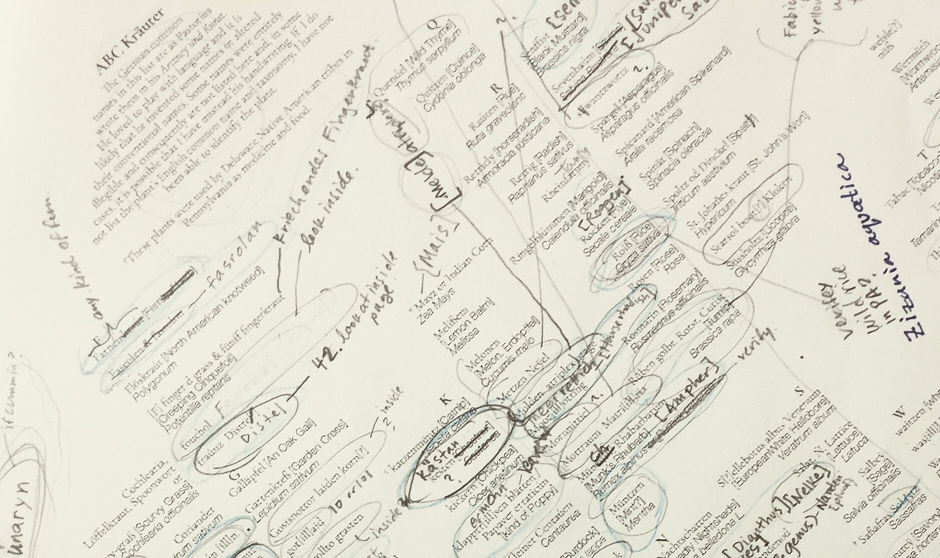

Plant common name translation process (2019)

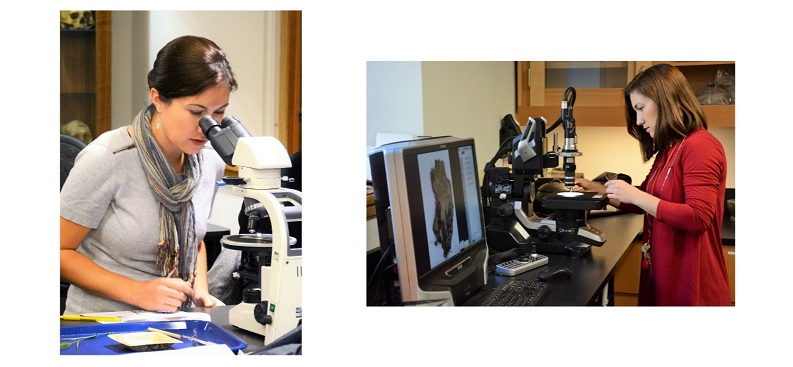

Chantel White: I'm the Teaching Specialist for Archaeobotany at the Penn Museum. I am an archaeologist, and I travel to archaeological sites while they're being excavated. I collect preserved plant specimens from the archaeological deposits and bring them back to the lab to microscopically analyze them. I try to identify the plant species that were present at the site, including the types of foods that people were eating, the medicines they were making from plants, and other ways in which plants could have been used. All of that laboratory work takes place in the Penn Museum at the Center for the Analysis of Archaeological Materials, which is abbreviated CAAM. I work with students there on all sorts of archaeobotanical projects from around the world, and I teach classes in ethnobotany and archaeobotany. One of those courses is “Plants and Society”, which Miranda took four years ago.

Chantel White at work. photos by Tom Stanley.

MM: I wanted to start our conversation with some questions. I have come to realize that people sometimes make gardens to tell stories about their own lives. They do this unconsciously, and also sometimes consciously, it depends on what motivated the individual to garden. The subject of my dissertation, Pastorius, who wrote volumes and volumes about his garden, was very intentional about writing stories into his garden.

He wrote about plants, soil, water, and things like that, as a part of the story of his own life. I was curious, Chantel, in your work as an archaeobotanist, can you describe an unusual example of a gardener or even a community of gardeners or culture of gardening? One that you found particularly interesting or unconventional or that told an unusual story about that gardener, the people or the place where that garden was?

CW: One archaeological site that comes to mind is about 4,500 years old, and it was an early village. We might not even call it a village yet-- actually it's more of a small community, I suppose. This community was living along the southern Dead Sea in what is Jordan today. From the archaeobotanical evidence, we can see that the residents had agricultural fields, and they were growing grain and other crops. I think it depends on how you want to define a “garden”, but certainly they had vineyards and probably orchards that were located near the site. The vineyards would have taken years of careful cultivation to produce grapes.The vines don't grow naturally anywhere around the Dead Sea; it is very hot and the area receives just 1/10th of the rainfall grapes need to survive. Even 4,500 years ago, people would have been working year-round to keep these vineyards irrigated, healthy, and producing fruit.

In total we identified 4,000 grapes and grape seeds from this particular site. It is clear that a main focus of their time and their economy was on the maintenance of vineyards and presumably the production of wine. I often think about how much time and effort would have gone into producing wine in such a hot, dry climate. What was the reason behind it? Was it because wine was used for a medicinal purpose, a spiritual purpose, or was its use also related to the alcohol content? And, of course, how did the wine taste? But I think that's a story for another time.

MM: I think the same is true for Pastorius, he wrote a lot about his vineyard. He was not a vintner before he emigrated to the Pennsylvania, but in 1705 he was excited to report that he had received grapes from Germany to plant his vineyard, and his first planting was 30 vines and then as as the years went by he reported one year he had grafted over 100 vines.

In Germantown he also talked a lot about the wild indigenous grape vines that were growing in Pennsylvania when he arrived, and I can assume that he probably tried to cultivate them as well, because wine was very important to him. His Monthly Monitor is filled with recipes for not just wine, but various kinds of alcohol used for their flavor and as medicine. Alcohol was palliative, but I also think that wine was a very important part of the pleasures of eating and drinking. His vineyard was not the only vineyard in Pennsylvania at that time. So there's a shared experience there. But, alas, in the end, his vineyard stopped producing to his expectations. Who knows exactly how many bottles of wine he was able to produce.