Exploring and Creating Collaborations in Colombia: A New Environmental Justice Resource

January 21, 2021

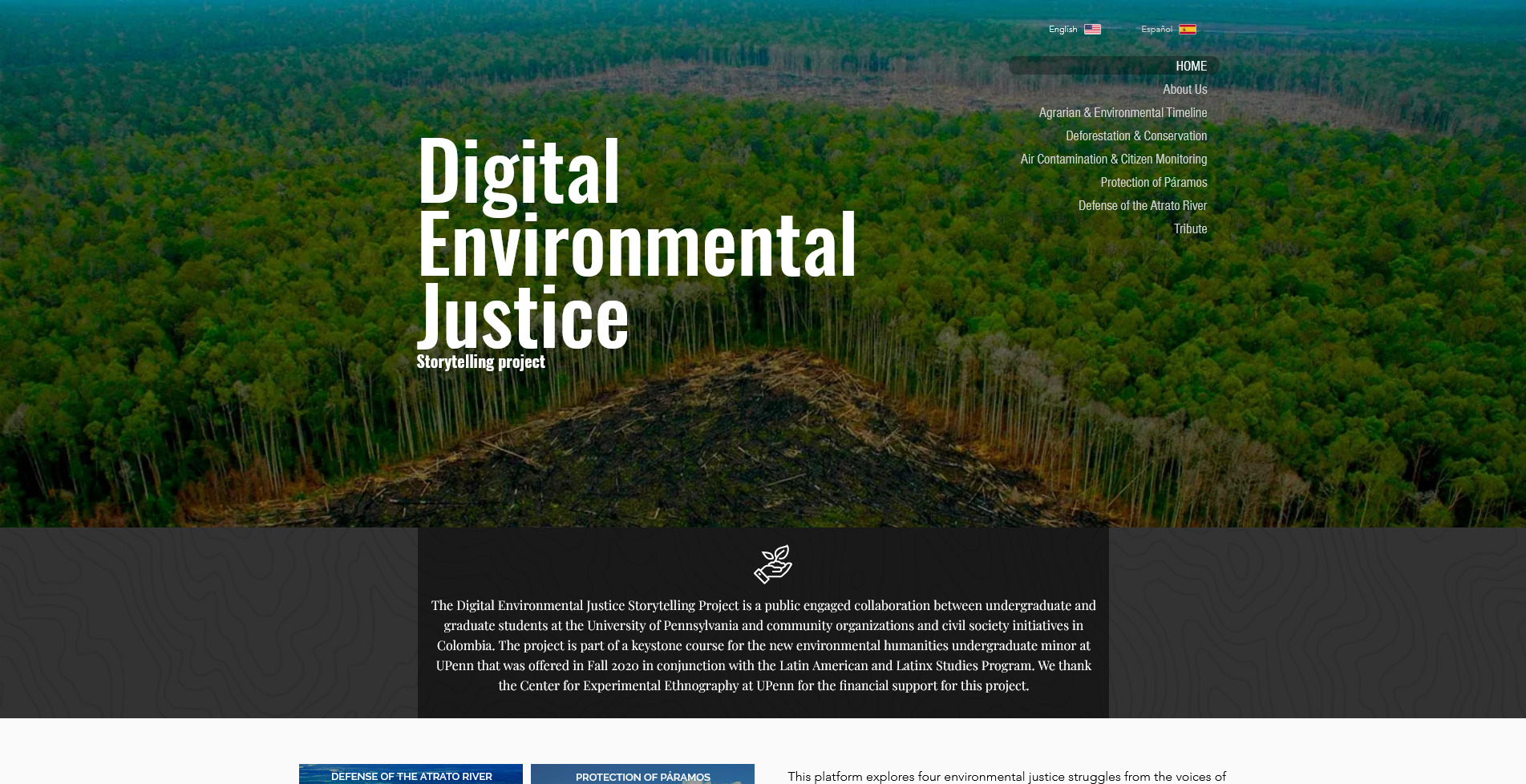

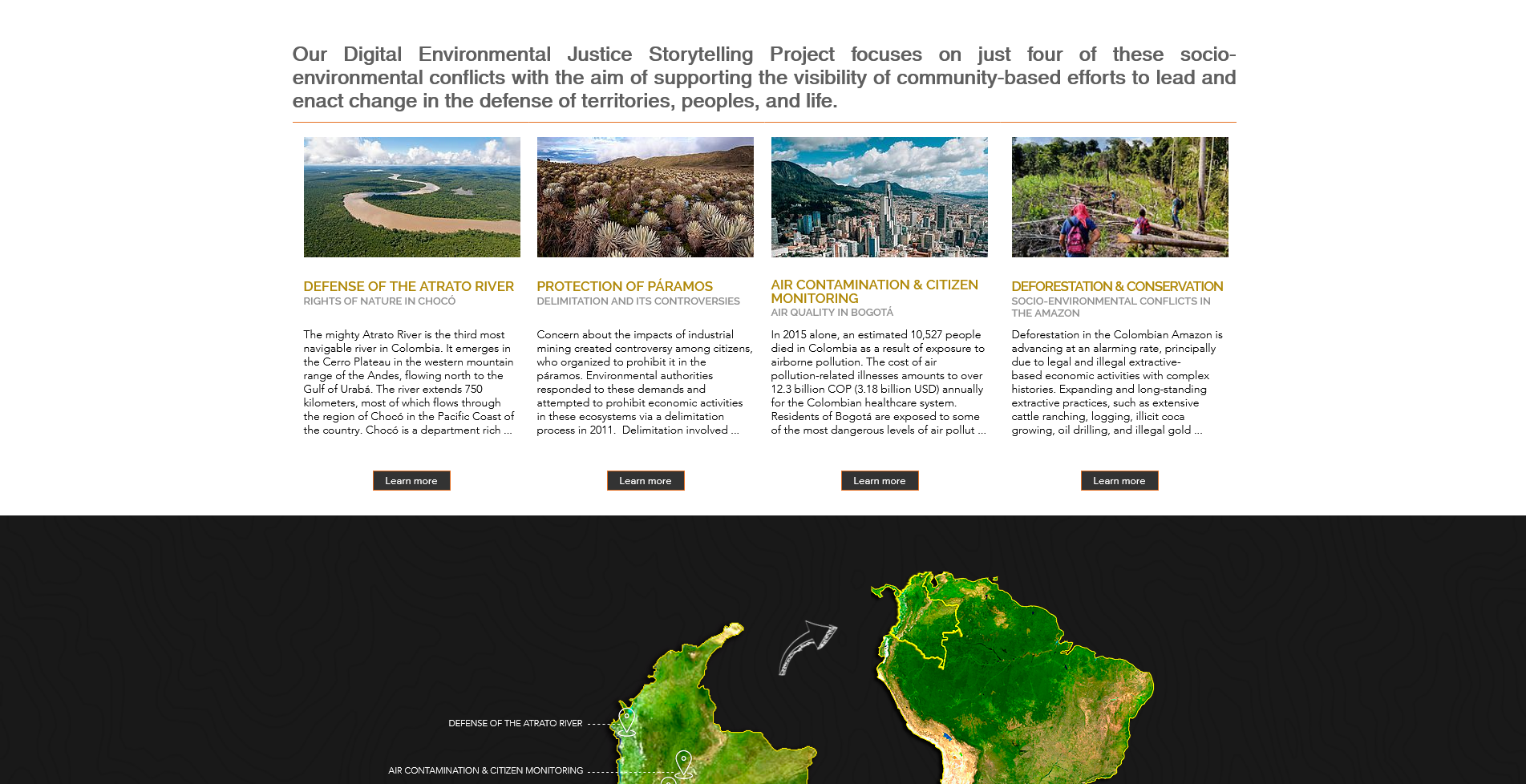

How do an anthropologist and a physician teach a new, transdisciplinary class in two languages, across hemispheres, in one semester and emerge with a rich and compelling resource that addresses issues of environmental justice across dynamic communities in Colombia? We joined Drs. Kristina Lyons and Marilyn Howarth, their students from ANTH 310: Transdisciplinary Environmental Humanities, and their collaborators in Colombia on December 21, 2020 to hear about how they created the The Digital Environmental Justice Storytelling Project. We spoke after the event to learn more about how they facilitated student work and what makes PPEH’s support of this project unique.

PPEH: What was most exciting to you about the conversations that were generated in this seminar?

Marilyn Howarth: I was very impressed with the level of insight and learning that the students had as they were engaging with the community partners. You could just see the growth in their insight and their, not just knowledge, but how they thought about environmental justice in Colombia. We would have a conversation in class, but then after they spoke with their collaborators, they were thinking and speaking about these topics with greater depth and passion. Engaging with community members and people actually doing the work matters, and it was really evidenced in the class.

Kristina Lyons: A lot of times, we are only able to read English based texts or we are only able to listen to English based discussions. In building the class, we wanted to decenter English and to create a space where there were multiple languages since different languages provide us access to multiple realities and worlds that we would not have access to if we were only working in one language. I also really appreciated the way that the collaborators and the community partners in Colombia and also the students, were up for that challenge--and Marilyn, as well.

PPEH: It seems like in building this resource you were able to really foster engagement cross culturally.

MH: You saw the engagement of the Colombian partners on the call today, and it's no easy feat to bring everybody together at a single time from another country. They came to the class through Zoom and made presentations. They spoke with the students on numerous occasions throughout the semester. The Colombian partners fully participated in this collaborative iterative process of gathering materials. Evident on numerous occasions was their appreciation of working with our students, in part because they saw their learning and in part because they were inspiring our students about environmental issues important to them. In some ways, in our pandemic time, using Zoom equalized the international nature of the collaboration making the interactions with the Colombian partners feel the same as our interactions with each other. It was the perfect semester to have this inaugural class using Zoom.

KL: For me, that was key. Some of the students and our colleagues from Colombia mentioned the importance of maintaining the complexity and situated nuances that really make the difference in the kind of stories that one can tell that depart from conventional or dominant narratives. These details reveal the importance of focusing on community knowledges, perspectives, practices, and territorial and neighborhood-level embodied experiences. We sought to reflect this on the digital platform. Cross cultural engagement implied doing this without getting lost in the situated details, but treating these details and differences respectfully because they are so relevant to the struggles of the communities that we highlighted on the platform and what they are attempting to transform: for instance, the ability to build more links between their social movements, between citizen-led initiatives, but also eventually having some level of policy intervention.

PPEH: In what ways has being a part of PPEH shaped your work?

MH: From a medical, health and science background, my work before engaging with PPEH was very traditionally science-based. Through the collaboration with PPEH faculty members I have seen how others engage around environmental and health issues. Using a different lens has really enriched my thinking about a lot of these issues. My lens has been broadened in a way that inspires me. I think that I have brought some of the hard science and medical aspects into their view. I have enjoyed seeing the intellectual growth on both sides. As a direct result of being a part of PPEH, we have together worked on local environmental problems like the PES refinery in Philadelphia and the concerns of residents living nearby.

KL: PPEH is a space that supports our public engaged scholarship; this is a home for that... but in our broader academic world this is not always the case. To have a place where this kind of scholarship is promoted and supported, is so important. To me PPEH has really facilitated me to remain being a practitioner of the kind of scholarship that I want to be doing in the world, and the collaborative work that I am engaged in with my Colombian colleagues and communities. For that, I am very grateful and appreciative.