On Water Retrospective: Walk Around Mingo Creek

December 12, 2018

On the eve of PPEH Rising Waters Fellows' trip to India for the Penn Winter Institute in Mumbai, we're looking back to the warm days of the Summer On Water Intensive. This is a guest blog post by Philadelphia writer Ann de Forest, who, alongside Adrienne Mackey, and JJ Tiziou, facilitated a "Walk Around Mingo Creek" on the 8th day of the 10-day summer intensive.

June 27, 2018

Several weeks after we led our Walk Around Mingo Creek as part of PPEH’s On Water Intensive, an old memory surfaced. It took me by surprise, a remnant from decades ago, long before I lived in Philadelphia or even suspected that I would end up living here. I was visiting a friend in Swarthmore, and we were driving somewhere near the airport. Back then, I-95 did not connect through the city but ended just south of the airport, unceremoniously dumping drivers on a labyrinthine road set up on low concrete pontoons that twisted over marshlands. That’s my memory, at least. I could picture that drive, the water on either side, nearly level with the road, the cattails, lily pads, and beach grass so close to the car, I could reach out and pluck tassels of grass as we passed.

This was the same area we walked with the On Water Intensive at the end of June, although that time I-95 rose above us, a literal “high” way that distances drivers from the wetlands below.

That June walk, like every other Walk Around experience, beginning with our first 5 ½ day journey along Philadelphia’s perimeter in February 2016, had a ripple effect. Walking has a way of dislodging buried memories, especially memories of place.

“Ripple” is an appropriate word for this most recent Walk Around experience. PPEH’s 10-day On Water Intensive, as its name implies, was designed to create awareness among the 28 participants that Philadelphia, built on a site between two rivers, is situated on an elaborate riparian system, veined with creeks that flow between Schuylkill and Delaware. While modern-day Eastwick, Philadelphia’s most southwesterly neighborhood, the airport, and the now fully connected I-95 all do their best to deny water’s presence (or should I say influence), that very denial, as we discovered on our Walk Around morning, at once shapes and threatens the area around the now mostly suppressed, paved over, and diverted Mingo Creek.

We were thrilled when Bethany Wiggin invited our Walk Around Philadelphia team – Adrienne Mackey, JJ Tiziou, Sam Wend, and me – to lead a walk along Mingo Creek on the eighth day of the On Water Intensive. Since walking the entire perimeter of Philadelphia together as a Swim Pony Cross-Pollination project in the winter of 2016, the four of us have been seeking opportunities to extend the experience and practice to others.

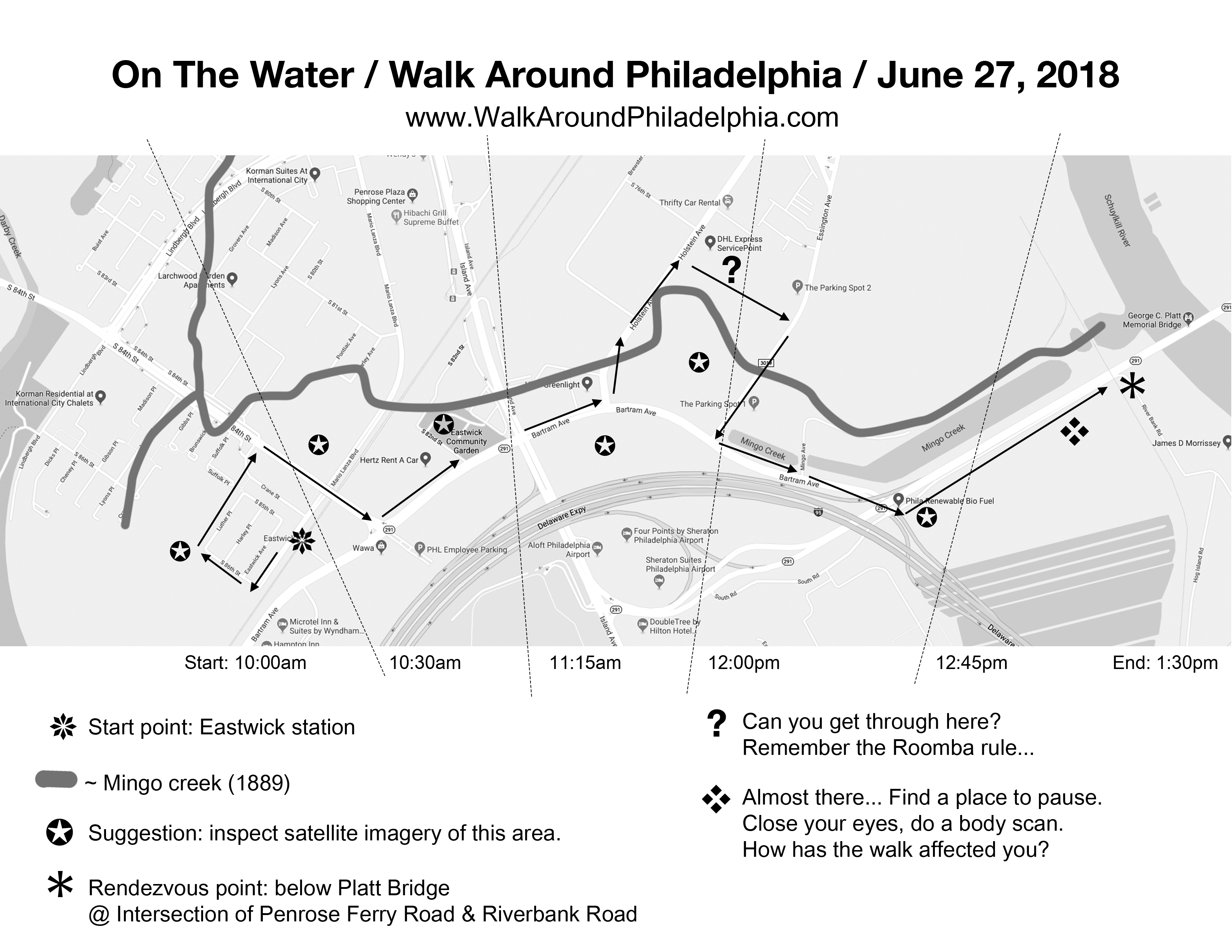

The On Water Intensive would be our first proof of concept, and we realized we had some things to figure out. We knew we didn’t want to “lead” a walk in any traditional sense. We did not see ourselves as guides, but fellow travelers. Besides, the On Water Intensive class, having explored the environs and tributaries of the Schuylkill for more than a week before we met them, would know far more than we do about the area’s topography, ecology, and history. But “Walk Around,” as we’ve dubbed our group and our practice, is all about shedding expertise. What we had to offer was an attitude, an approach to experiencing a place by walking through it, cultivating an openness to surprise and discovery along the way. So we decided to frame the walk as an invitation. We divided the class of 28 into small groups of four or five, giving each group a map that JJ had made, which charted the original meander of the now erased, vestigial Mingo Creek.

The map served as a rough guide, showing a starting point and a common destination, where we would gather a few hours later to share our stories. We wanted each group to have the freedom to explore and discover the terrain on their own. We drew up a few guidelines and ground rules, and handed each group an envelope with prompts to encourage reflection, discussion, or action along the way. “Remember the Roomba rule,” JJ wrote on the map, an axiom from our first walk together when we realized we approached the city’s boundary line like those Roomba robot vacuum cleaners, going as far as we could until some obstacle pushed us off in a different direction.

The map served as a rough guide, showing a starting point and a common destination, where we would gather a few hours later to share our stories. We wanted each group to have the freedom to explore and discover the terrain on their own. We drew up a few guidelines and ground rules, and handed each group an envelope with prompts to encourage reflection, discussion, or action along the way. “Remember the Roomba rule,” JJ wrote on the map, an axiom from our first walk together when we realized we approached the city’s boundary line like those Roomba robot vacuum cleaners, going as far as we could until some obstacle pushed us off in a different direction.

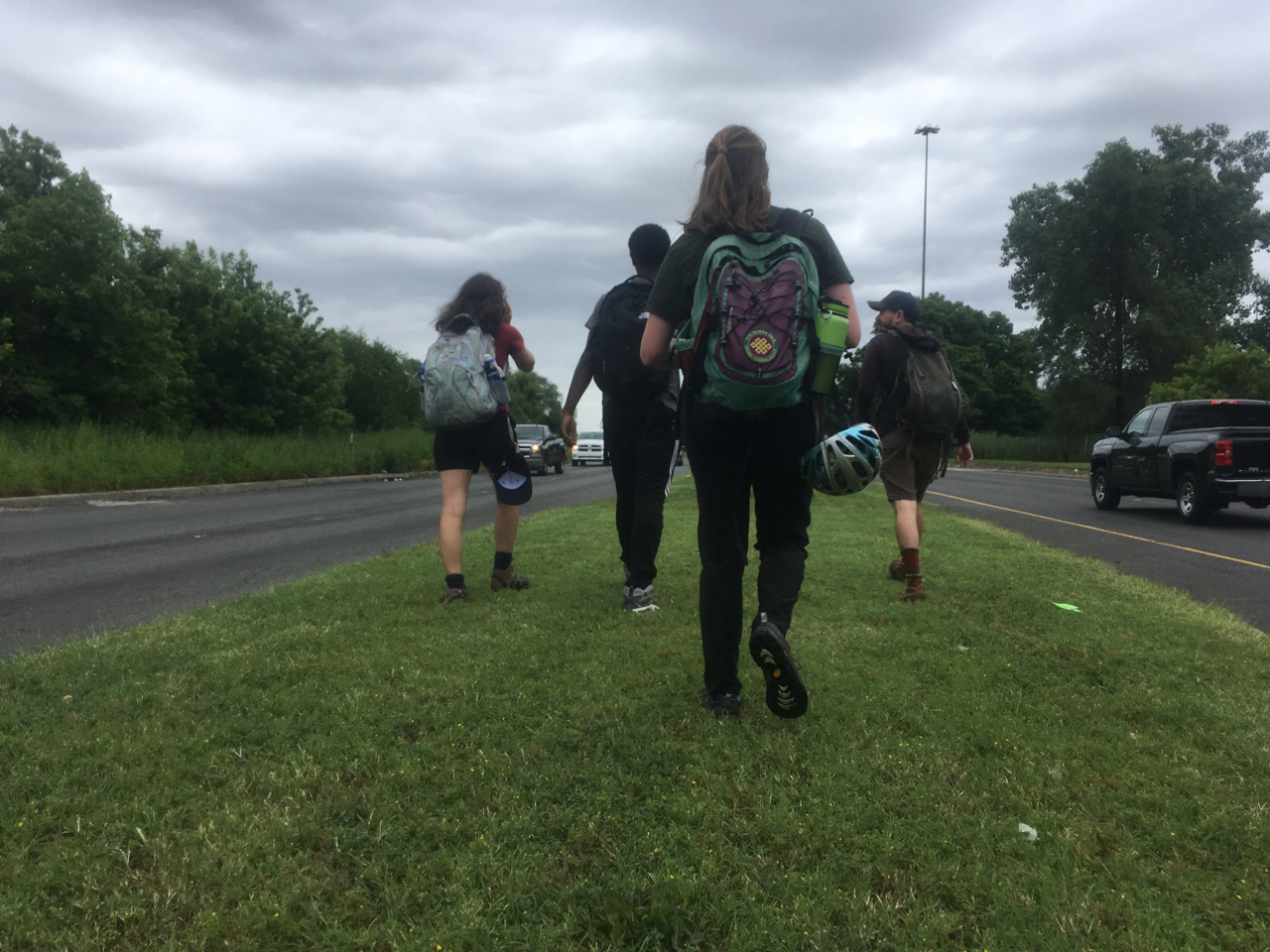

Dividing the class into small groups was important. From experience, we knew that not all the discoveries made in a Walk Around involved the surrounding terrain or cityscape. There’s an intimacy that develops in a small group, a thrill of shared adventure as you negotiate challenge and risk or solve how to navigate an unexpected, but inevitable barrier -- chain link fence, dead end, locked gate – invoking the Roomba rule.

As the groups disperse, Adrienne, JJ, and I (Sam unfortunately couldn’t join us) set out on our own, fellow explorers rather than guides or leaders, and head for the woods. JJ has done satellite reconnaissance before the walk began and has noted strange patches of asphalt, an abandoned road, an overgrown trolley track. We start our day entangled in blackberry briars and shoulder-high grass and wildflowers, then emerge into a residential neighborhood that feels like a remote outpost of a lost city, even though the houses all appear inhabited. These 19th century brick houses were once connected as twins and rows in a denser, urban fabric. Now they stand as single brick structures surrounded by trees and grass, a crumbling neighborhood pushed up to a blurry edge where the city devolves into empty, overgrown lots. The names of streets on a crossroads sign are obscured by vines, and one of the streets points back into the woods, the road itself erased. Urban renewal clearly plowed through here once, evident later when we pass by Korman’s sprawling International Village, an abandoned Brutalist middle school, the enormous asphalt island of Penrose Plaza, and whimsical public art works (a field of wooden sheep and cows that double as benches; a ring of antique bureaus that cite highlights in Eastwick’s history on their drawers) with no public to appreciate them. Now we’re witnessing what appears to be the opposite, equal reaction, urban disintegration in process.

We are deep in the woods when we draw our first prompt. “If you arrived in this place from 300 years ago, what would surprise you most?” We laugh, because a visitor from the past would feel at home among trees and birdsong. Though I wonder out loud whether these species of trees or birds were native to this region, or are, like us, alien invaders. But it is the ever present whoosh of traffic, we realize, that would most shock a visitor from the past. The sound might be mistaken for rushing water or a strong wind, but that current of internal combustion engines propelling rubber tires at high speeds over asphalt would have troubled the 18th century woods walkers. They would have recognized the signs of impending cataclysm.

After walking for a while along train tracks and the rough, pedestrian unfriendly sidewalks and road shoulders along Island, Bartram, and Holstein Avenues, past a sea of hotels, off-site airport parking and car rental lots, and business headquarters (like Uber) we didn’t know were located way out in Southwest, everything starts to look apocalyptic. A plunge into another patch of woods skirting I-95 reveals a massive graveyard for tires. The magnitude is staggering. The black mounds spread for acres. The stacks are interwoven so artfully and intricately that their presentation seems almost intentional. We are baffled. Illegal dumpers with artistic inclinations? Who is their audience? And if they could spare the time to create such elaborate compositions, why couldn’t they find a legal dump?

In those same woods, we stumble upon an encampment of shacks, striking in their improvised domesticity. Whoever lives or lived here made an effort to make a home here, off the grid, out of sight under the highway, hanging printed cloth for curtains and converting tires into planters for herbs and vegetables.

On this day of the On Water Intensive, we don’t encounter actual water, what remains of Mingo Creek, until nearly the end of our journey. The creek, which once flowed across the entire area we walked, has been shrunk and protected behind a high chain link fence by the Water Department. Signs post warnings about the creek’s depth and danger. The water seems stagnant, not fluid at all. Only when we reach the Platt Bridge, at the edge of the Schuylkill do we see how the two bodies of water still connect. Mingo Creek flows, or rather seeps, into the Schuylkill right by the massive oil fields that dominate both banks of the river.

Walking along the bridge’s heavy infrastructure of concrete and painted steel, we pick our last prompt. It is the same as our first. “If you were a visitor from 300 years ago…” Adrienne gazes at the oil drums and spheres, the soaring span of the bridge, the water treatment plant. We are surrounded by infrastructure alien and inexplicable even to our jaded eyes. How would our 300-year-old traveler respond? Would they believe that humans could conceive and construct such monstrous wonders? “There must be great and mighty Gods,” Adrienne declaims in the voice of the 17th century visitor, “Fearsome giants!” We laugh at the hyperbolic theatrics, yet in the distance, the high tower that burns a steady, crackling flame turns as frightening as Sauron’s all-seeing eye.

Everything is connected. Highways, waterways, railroad tracks, and the massive and mysterious energy infrastructure we can barely wrap our minds around. We focus on the miniature, the tangible, and the edible. All morning I have been picking Queen Anne’s lace, phlox, loose strife, gathering my Mingo Creek bouquet of delicate flowering weeds, some native, some invasive. JJ has been avid as the birds in spotting and consuming mulberries en route, and they grow especially abundantly along the pillars of the Platt Bridge. His hands are stained purple by the time we reach our meeting point. He shows them off to the groups of walkers as they begin to gather.

Every group brings its own tale and unexpected treasure. “We Roomba-ed into a wholesale coffee roaster and distributor, and they made us espresso,” reports one and JJ, Adrienne, and I delight to hear the Roomba rule converted to a verb. Others report of a long exploration of Eastwick’s sprawling community garden, which included an invitation from an elderly Vietnamese couple to sit under their awning and sample their tomatoes. One group pushed through a barely open door in the abandoned school to explore a graffitied underworld, convinced at every turn down another dark corridor that they had stepped inside a horror movie, with zombies posed to attack. The school grounds were littered with classroom artifacts, and one participant lugged the carved hull of a model wooden boat in his backpack. Someone else, in another group, had taken the same boat’s mermaid figurehead. The discarded, broken boat was reassembled when the groups convened. The group that included two of the Penn professors, Bethany Wiggin and David Barnes, ended up being the boldest of all, striking off toward the water through a field, refusing to accept even a high chain link fence as a barrier. Hierarchies of position and authority dissolved, they said, when teachers had to accept boosts over the fence from their students, and when they together landed in a long-term airport parking lot.

On the route map that we distributed, JJ ended a list of suggested routes and landmarks to explore with a large question mark. “I took that question mark seriously,” David Barnes told JJ and me later in the summer, “It was everything.” It gave him permission, he said, to forge ahead with his group through a field without knowing exactly where their unconventional path would lead. “The question that kept us going was ‘how do you get through?’” he said. The answer turned out to be scaling a fence.

The rewards of Walk Around, we were happy to discover, expand when others share in the experience, following different, parallel routes. Walking in parts of the city where walking is an uncommon and even discouraged mode of transit never fails to yield surprising discoveries and insights.

Every time since that day that I’ve driven on I-95 to the airport, I look toward the thick tree canopy at the edge of the highway, and see, in my mind’s eye, what lies beneath, those sculpted stacks of tires, that small encampment, fields of unseen wildflowers and blackberry thickets. Over in the light industrial zone, I know now there’s a small entrepreneur roasting coffee. I glimpse the oblong pools of water where Mingo Creek survives. And I remember now that long ago drive through the marshes before the highway was finished.

Our Walk Around experience with the On Water Intensive was exhilarating, even though the prevalence of trash, parking lots, and oil fields, the caged water and paved wetlands leave me depressed about the havoc we humans wreak as a species. Our future – and especially the future of those who live in Eastwick, a precariously paved wetland at the mouth of a tidal river -- is uncertain. But I’m also impressed by the resilience of non-human species, birds, butterflies, mulberry trees, who survive both because of – and in spite of – our intervention. Near the end of our walk, we passed a solitary peach tree, growing from a sidewalk crevice near the I-95 on ramp on Holstein Avenue, laden with unripened fruit. Somebody once, without much thought, flung a peach pit out a car window (just like countless others had flung soda cups, cigarette butts, plastic bottles of pee, and other debris we stumbled across along the way). Somehow that pit nestled into a patch of soil under that cracked concrete, and found a suitable place to take root, grow and thrive.

All photo credits to JJ Tiziou