What's in a Name? The Anthropocene, Part 1

March 15, 2018

This year's PPEH undergraduate fellows represent a range of scholarly fields, modes of inquiry, and creative practices. Together, they have reflected on their ideas surrounding the concept of the "Anthropocene." In particular, they responded to the following prompt: How has recognition of the Anthropocene influenced your thinking about your trajectory in terms of research, scholarship, career, life? This is the first in a series of three posts regarding the Fellows' own thinking and critical pursuits within a moment of profound human imprint on our environment.

FROM THE MIDDLE OF "NOWHERE" TO THE "MIDDLE OF SOMEWHERE"

Ana Alonso, Linguistics and Environmental Studies

The past four years have imbued me with an appreciation for migratory birds. While many species have rigid requirements for their summer habitat, their migration path is flexible and opportunistic, often adjusted to follow key resources. My orientation to my wintering ground evolves each year: I've spent my past three summers in the mountains of the Flathead Nation in Northwestern Montana and my past three winters in Philadelphia. Although I feel an unparalleled connection to Montana, every year I'm congratulated upon my return as emerging from "the middle of nowhere" to come into "civilization."

My first two years at Penn were characterized by an entrenched disdain toward the urban environment. I didn't want the urban landscape of Philadelphia to be prioritized as a societal endgame, and dismissed the green spaces around me as unrepresentative of "real nature." My frustration culminated in an "unsanctioned study abroad" to spend my sophomore spring Montana. During my stay I became entwined in several efforts to revitalize and advocate for traditional ecological knowledge and traditional management.

My "unsanctioned study abroad" primed me for a more productive return to Philadelphia. I had embraced locally-defined standards of the Confederated Salish. However, just as mainstream standards of progress cannot be applied to sovereign, culturally distinct polities, Salish standards cannot be applied in an urban framework. Potawatomi scholar Robin Wall Kimmerer recognizes this reality and urges non-Indigenous Americans to "undergo a process of becoming Indigenous to this place." Chiefly, however, this process must be non-imitative.

In the built environment, we too easily exempt ourselves from this responsibility by relegating conceptions of "real nature" to outside city limits, minimally affected by personal action. Over the two years, I have embraced my migratory annual cycle and looked to adapt to and appreciate the unique ecological milieu of Philadelphia. I am excited to be involved in an organization documenting developing "Indigen-ish" local environmental relationships through projects like the Eastwick Oral History Project!

THE INVISIBLE LAYERS OF THE ANTHROPOCENE

Seung-Hyun Chung, English

I am not a long-standing environmentalist. Except for the occasional appreciation of nature tours and mountain hiking, I’ve given little thought to sustainability and environmentalism throughout my life and academic study. I’ve known the importance of these issues, but never expected myself to be the one to explore them as a scholar and artist. Ironically, I found my way to Environmental Humanities and the recognition of the Anthropocene from a rath selfish reason: I (only) care about people.

At Penn, I’ve studied literature and media, focused broadly on global human rights, race and ethnic studies, and trauma. I found myself drawn to those subjects partially from my own experiences as an Asian American but also from my desire to validate stigmatized identities and histories. Storytelling has always been my preferred mode of activism, as they can enlarge moral capacities and change perceptions toward people traditionally considered “the other,” including myself. I knew early on that I wanted to be an activist-scholar and artist who could create reparative knowledge and storytelling for the damaged and oppressed.

Photo from my art exhibit, Sensitivities. A visually pleasing photo of tea estates in the Nilgiri Mountains in Tamil Nadu. These tourist-friendly sceneries hide the layers of deforestation, corporate tea production, and the manipulation of indigenous labor to produce these tea estates

It wasn’t until I read Chakrabarty’s “Climate of History,” however, that I noticed a fundamental gap in my perception of social justice. In his essay, Chakrabarty asks the poignant question, “Is the Anthropocene a critique of the narratives of freedom?” (210). Merging issues of global climate change with the pursuit of freedom, Chakrabarty addresses the way geologic and environmental history cannot be divorced from human history—namely, the histories of colonialism, industrialization, and neoliberalism that have enabled the appropriation of human bodies and natural resources. Indeed, the origins of racial formation, gendered and class hierarchies could be traced to the point in which the environment became externalized out of the human self. Framing our current period as the Anthropocene recognizes this entanglement and demands human accountability toward both environmental and social justice—the very concepts that originate from the “narratives of freedom.”

To approach the Anthropocene has served to fundamentally break open the cosmology that I’ve abided with throughout my life. The scholarship and art I produce must address the politics of disposability across environmental and human subjects. As I realize that the boundaries of so-called humanhood are fluid, I want to be part of the movement to rewrite these boundaries and make us accountable for the damages to each other and to this planet. Though I cannot claim to be an environmentalist quite yet, slowly, I am becoming one.

Link to Chakarabarty’s article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/596640

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. "The climate of history: Four theses." Critical inquiry 35.2 (2009): 197-222.

THOUGHTS ON THE ANTHROPOCENE

Emma Singer, Urban Studies

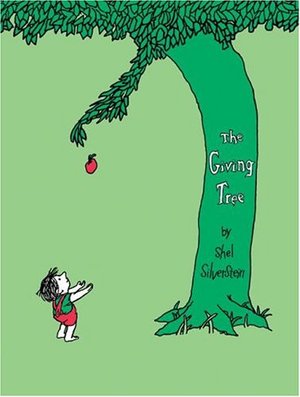

The basic story of Shel Silverstein’s (1964) The Giving Tree goes like this: boy meets tree. Boy asks the tree for everything it has (its apples, branches, and trunk). Tree acquiesces. The story ends when the boy is old and the tree is a stump which he uses to rest upon.

“And the Tree was happy”.

Is this a story about a deserving boy and a selfless tree of strong moral fiber? Or is it the tale of a selfish human exploiting a natural resource for his personal gain. After all, once the tree has become a stump, it can no longer provide shade or apples to the masses, having only really benefited the boy.

Through the latter lens, The Giving Tree transforms from a children’s book to a metaphor for the ways the Anthropocene is directly entrenched in the modern system of capitalism. Without the tree, the boy would not have been able to make money by selling apples, afford a home by taking its branches, or sail away by carving its trunk into a boat. This mirrors the real world, where natural resources (i.e. oil, lumber) become seemingly free commodities from which we can accrue monetary value. The Anthropocene is only possible through this commodification of nature. Therefore, to address the violence and environmental degradation of the Anthropocene, we must first challenge the same issues inherent with modern capitalism.

With all this in mind, perhaps it’s time to mention that Shel Silverstein thought people are reading too far into The Giving Tree. He claimed it had no message. All Silverstein wanted to do was write real stories that, in the end, just ended up being kind of sad.