by Azd Billeh

I remember hearing my grandfather tell me stories about the beauty of life in Palestine when he was a child prior to the Israeli occupation. He shared vivid descriptions of walking around Jerusalem and interacting with people of diverse ethnicities, religions, and backgrounds in what was a cultural meeting place for various tribes and individuals who coexisted together peacefully. I would ask him, “Jido, what makes Jerusalem hold such a special place in your heart until now?” and he would spend hours describing the beauty of the land, architecture, and people that used to live and circulate freely in Jerusalem ranging from Al-Aqsa Mosque’s breathtaking architecture to the quality of water that used to traverse the different cities within Palestine and beyond. My grandfather’s stories still resonate with me, and as I grew older, I wanted to understand more about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and how important a role water plays in the quality of life in Palestine.

This is a story of how the land of my ancestors was stripped away from them.

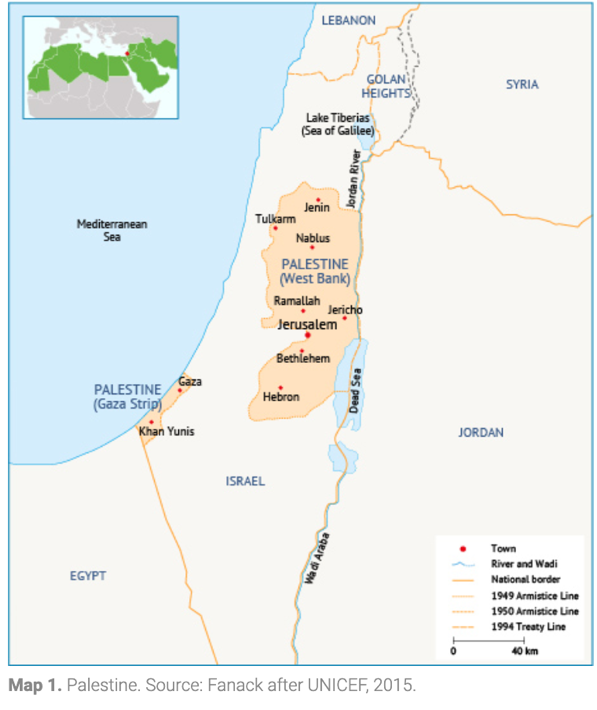

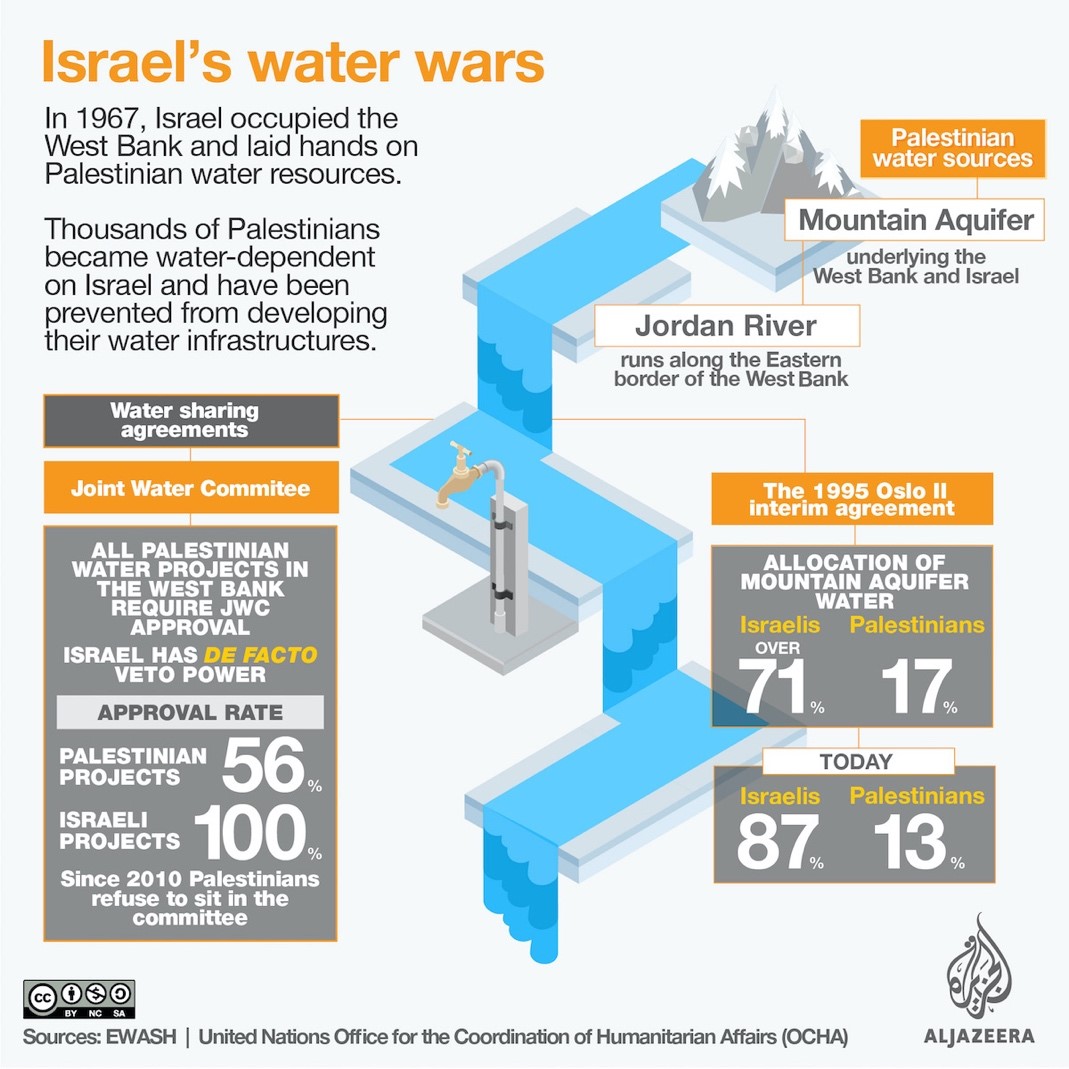

Upon the inception of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in 1948, Israel has had de facto veto power over Palestine. When the UN General Assembly passed resolution 181, it stipulated the partition of Arabs and Jews in favor of the Jews in Palestine. A few years later, war was nonetheless inevitable as a result of an influx of Zionists into modern day Israel on Palestinian land. The conflict over water throughout Palestinian territory began escalating in the early 1960s when the distribution of political power and control over the territory began to strongly favor Israel. There was no mode of transportation for the water from the Gaza Strip to the West Bank (see Map 1) leading Palestinians to struggle to gain access to clean water over long distances. As a compromise, Palestinians started purchasing water from relatively expensive domestic Israeli supply chains, such as Mekorot, creating a perpetual hierarchy between both citizens in the region as the Palestinians began to rely-on an Israeli company to sustain their lives. Over time, Israeli water suppliers grew more and more powerful, subjugating poor Palestinian farmers who are unable to cultivate the local land/soil let alone have a sustainable supply of potable water for their day-to-day use.

In 1995, the Oslo II Accord was signed in an attempt to reach peace between Palestine and Israel with the aspiration of creating a relatively equal divide between the two lands. The accord entailed that a Palestinian Authority (PA) would be established to engage in interim governmental independence within the West Bank and Gaza Strip over five years. In turn, this accord declared that Israel would control the movement of water to and in Palestine and provide the Palestinians with a fixed supply of water each year dictated by Israeli officials if Israel agreed to withdraw from Jericho and Gaza, two of the main cities in Palestine located near the Jordan River and Mediterranean Sea (see Map 1). According to Al-Jazeera Palestine, Palestine’s allocated percentage of water is merely 13% whereby Israel controls more than 87% of the distributed water sourcing from various mountain aquifers, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Israeli controlled Jordan River.

As a result, the Palestinian economy has plummeted. Various proposals for different projects entailing water as a primary input for Palestinian industries, such as the Deir al-Balah project, have been rejected for further funding by Israeli officials due to the high-energy consumption of other industries located in the Gaza Strip that exceed Israeli established energy thresholds. This problem, however, is further exacerbated because the struggling state of Palestine has been unable to invest in alternative renewable energy sources. Several plans to open Wastewater treatment systems in Palestinian territories have been left stagnant due to the rigidities of the Oslo II accord, which restricts the ability to set different energy thresholds for the projects and places a cap on the amount of water each plant can use. It is important to emphasize the ever-growing water injustices occurring in occupied Palestine because these injustices have often been overlooked in analysis of the political conflict in the region.

(Al Jazeera, 2019)

Despite this complex situation, I can envision economic, political, social, and environmental transformations for both Israel and Palestine if proposals are made to deal with the injustices and if collaborative efforts are made by all actors involved to take seriously the interconnectivity between water, land, and human rights. For example, there is a large amount of sewage effluents produced by regions, such as Nablus and Ramallah in Palestine, that could be transformed into fertilizer and redirected using basic irrigation techniques to Palestinian farmers in the Jordan Valley. Such an endeavor could help to improve agricultural productivity and food security and autonomy throughout the region. This would help ease the economic and water dependencies that have been created since Palestinians would no longer be forced to purchase water from the Israelis at relatively high prices. An alternative solution, would be to build water salination plants in the Gaza Strip that would help sustain a healthy water reservoir for the entire population. This could help forge an alliance between Israeli and Palestinian citizens through collaborations that would begin to maintain a two-way relationship over water management. Although it can be argued that such salination plants would create excessive short-term stress on local Palestinians living in Gaza because of high levels of land occupation, the overall net-effect could be positive if local opportunities for sustained employment are also created. This could also lead to an improvement in the psychosocial health of a majority of Gaza Strip residents if qualitative differences in water quality and quantity are made, which would lessen people’s financial stress and public health risks.

(Al Jazeera, 2019)

I strongly believe that certain compromises on the part of both Palestinians and Israelis can lead to solutions that aim to democratize the governance over water. I hope that one day I can return to my home land of Palestine and witness the beautiful descriptions my Jido used to share with me as a child. The water injustices in the region will continue as long as the Israeli’s exert hegemonic control over Palestinian lives and territory. One can only begin to envision the traumas experienced by Palestinian families on a day-by-day basis as they struggle to provide water and safe sanitary conditions for their children. It is at times like this that I sympathize with my Jido when he reminisces about the land that once used to be a safe haven for many peoples and animals and where an array of exotic fruits and vegetables unparalleled by many other places in the region were produced. Water injustices have left the same trees my Jido used to pluck olives from as a child completely dehydrated and unable to flourish amidst the conflict. In the future, I hope to return to my homeland of Palestine to support struggles for water justice and to bring more global attention to this rights violation, as well as to how resilient Palestinians have been in trying to solve their water crisis while being governed by unjust laws that occupy and degrade the beautiful lands of my ancestors.

(Al Jazeera, 2019)