2019 Faculty Seed Fund Sprouts and Shoots: Part 5

March 4, 2020

This is the fifth in a series of Field Notes focused on the work resulting from the 2019 Research and Teaching Seed Funds. These short posts offer a brief look at the second round of emergent initiatives in environmental humanities being developed by Penn faculty with support from PPEH seed funds. Each of the projects was also featured in short presentations in February 2020 as a part of our Spring Brown Bag Series.

Jump to Part 1

Jump to Part 2

Jump to Part 3

Jump to Part 4

Reconstructing the socioecological memory of social and armed conflict

Kristina Lyons (Anthropology and Environmental Humanities)

In Colombia, there is growing public and legal debate over the way soils, bodies of water, forests, and territories are not only scenes, but also actors and casualties of war, requiring criminal prosecution and reparative treatment in the country’s post-peace accord and ongoing transitional justice process. Given the glaring absence of environmental issues in the 2016 peace accords signed between the national government and the guerrilla organization, the FARC-EP, certain environmental coalitions in the country have proposed reconstructing what they call the “environmental” or “biocultural memory” of over five decades of social and armed conflict. However, many scientists argue that limited knowledge for baseline environmental assessments exists due to the historical presence of armed groups in large swaths of the national territory. Simultaneously, the official demobilization of the FARC-EP has left areas previously conserved due to the dynamics of war vulnerable to new forms of environmental degradation upon the arrival of a reconfiguration of armed actors, mafia-narcotrafficking organizations, extractive-based, and industrial activities.

Deforestation in the Colombian Amazon during the post peace accord era. Puerto Guzmán, Putumayo. Photograph by author.

It is difficult to collectively imagine the actions that need to be taken to not only criminally prosecute the damages done to, but also the steps to remediate and reconcile with ecosystems that have been affected by multiple facets of violence without a sense of the way life had been organized and the complex configuration of actors that have intervened upon and come to make and unmake a place. A series of questions become important: Who and when did specific actors arrive, occupy, and transform a territory? What kinds of fauna and flora previously occupied and composed and decomposed a place? What were the quality and quantity of fresh water sources? What kinds of vegetal life covered the soils? How was land being used and by whom? How were territories affected by national policies, geopolitical interventions, and public order scenarios? What episodes of violence are most remembered by local communities, and which traces of this violence linger and continue to reshape the landscape and people’s everyday practices? These questions can inform popular processes of territorial ordinance in a post peace accord era where rural communities living in the historical epicenters of war begin to repair not only fractured social relations, but also to reconcile with their degraded soils, forests, and watersheds.

Community dialogues to analyze the socio-environmental conflicts of the Mandur River watershed in Galilea, Puerto Guzmán, Putumayo. December 2018. Photograph by author.

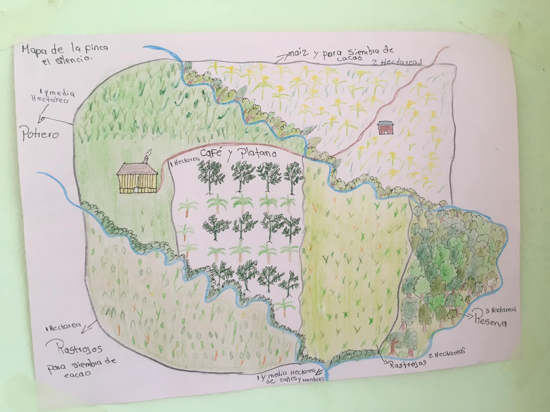

With the PPEH seed funds, I collaborated with a local NGO, Fundación ItarKa, in Puerto Guzmán, Putumayo, to begin a pilot project in October 2019 with rural communities to recover the Mandur River watershed located in the macro watershed of the Caquetá River in the Colombian Amazon. The watershed is contaminated by illegal gold mining and is also affected by the deforestation caused by the cultivation of illicit crops and extensive cattle ranching; all three activities are entangled with the history of armed conflict in the region. The pilot project built off a series of workshops and community dialogues that we organized between March and December 2018 to reconconstruct the socio-environmental memory of the watershed with the residents of the Mandur. The seed funds facilitated our work to delimit the watershed and to engage in social cartographies with rural communities that would support a process of popular territorial ordinance and the eventual reforestation of not only the banks of the river, but also its affluent water sources.

Maps of their farms drawn by residents of the Mandur River watershed, Buena Esperanza, Puerto Guzmán, Putumayo. December 2019. Photograph by author.

However, this community-led initiative was abruptly interrupted in January after a wave of violence, which included the assassination of five social leaders, the attempted assassination of two others, and the forced displacement of a series of families (all residents of the watershed) occurred due to a territorial dispute between purported dissident groups of the FARC over control of the cocaine trade and narcotrafficking routes in the municipality of Puerto Guzmán. Given the current public order situation, we decided, in consultation with the communities of the Mandur, to suspend our project. In the meantime, the methodologies that we designed and implemented with the rural communities of the Mandur River watershed will begin to influence a legal case led by the Special Jurisdiction for Peace in Colombia (the JEP), which is the transitional justice mechanism agreed upon in the peace accords to investigate and prosecute members of the FARC-EP, the public forces, and third parties that have participated in the social and armed conflict. The JEP opened a special chapter to treat specific territories and “nature” or the “environment” as victims of the war. This will be the first case in Colombia and in the history of transitional justice cases internationally to consider other than humans as causalities of war, and hence, in need of reparations. This continuation of our publicly engaged and transdisciplinary work will continue to be supported by a generous Dean’s Global Inquiries Fund Award.