Animal, Vegetable, Digital: On the Ecologies of Digital Manuscript Studies

October 25, 2019

Aylin Malcolm

As a PhD candidate in medieval literature, and as a new graduate research fellow at PPEH, I often think about the intersections between premodern literary culture and natural philosophy. In the past few years, I have also become interested in digital editing as a way of promoting access to medieval manuscripts. So when PPEH Managing Director Meg Arenberg asked me about “the relationship between [medieval] material texts and imaginative representations of terrestrial and celestial worlds,” I realized manuscripts actually offer a useful starting point for comparing medieval, ecological, and digital frameworks. In what follows, I tease out these comparisons, using my work creating online tools for accessing manuscripts at Penn to ponder the ecological implications of digital manuscript studies more generally.

To touch a medieval manuscript is to touch an archive of materials from medieval environments. Premodern scribes wrote in ink made from oak galls on the skins of livestock, or on paper made from hemp and linen rags. Pigments were made from molluscs (Tyrian purple), plants (indigo, weld), clay (ochre), and minerals (ultramarine, vermillion, malachite). Glue came from the swim bladders of fish, and many books were bound in wood and leather.

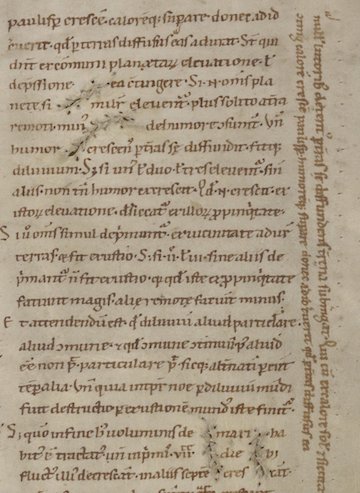

Even today, manuscripts often bear signs of their organic origins, such as remnants of animal hair. In some cases, the material has shaped the text; for instance, torn or scarred parchment may break up the lines on a page. These interactions between humans – including the scribes who nearly always altered the texts that they copied – and the bodies of nonhuman species were so diverse that no two copies of a medieval text are identical.

Detail of a page from William of Conches’s De philosophia mundi, a twelfth-century scientific text covering astronomy, geography, meteorology, and medicine. The scribe has worked around several tears in the parchment. Kislak Center for Special Collections

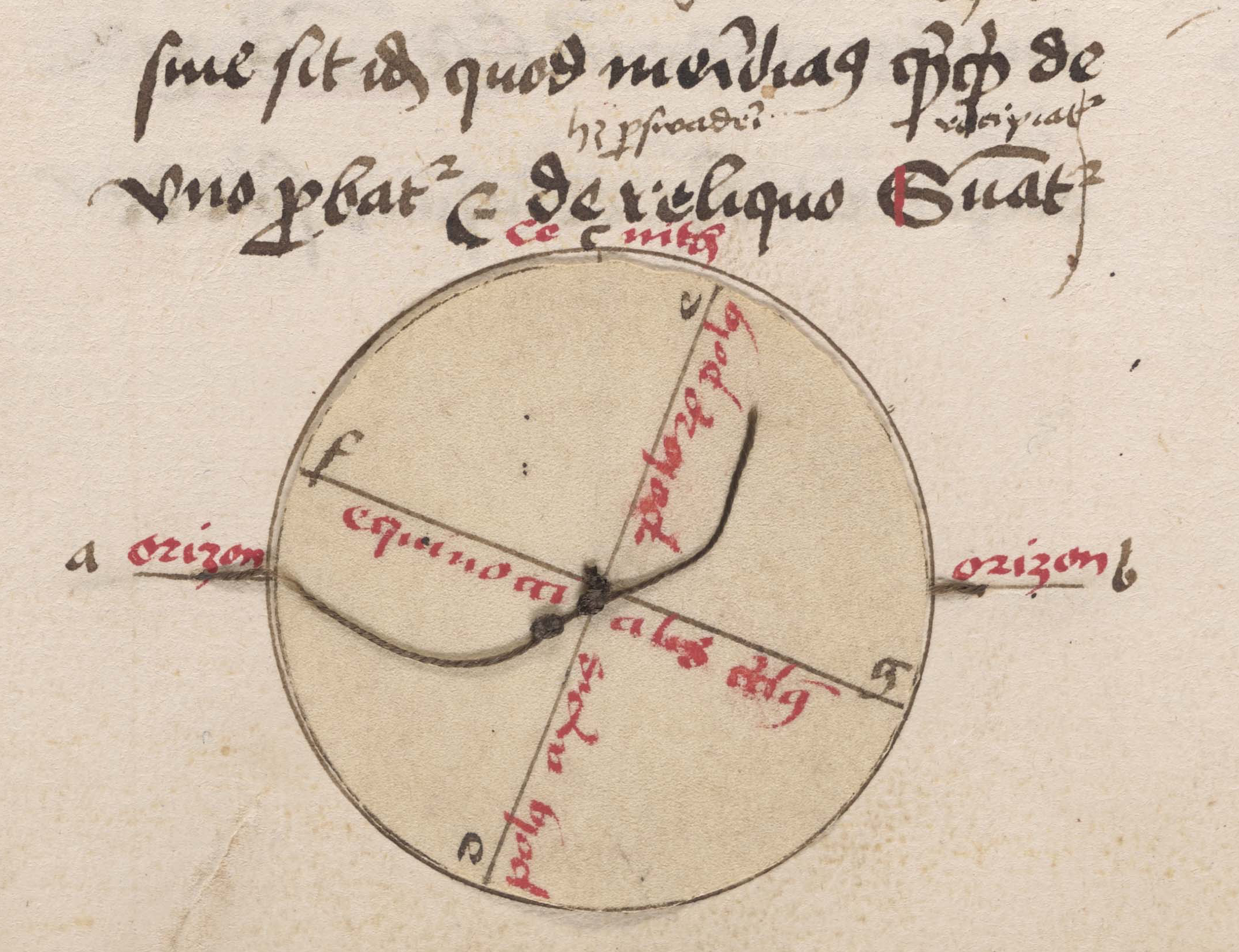

These characteristics of manuscripts also reflect broader tendencies in premodern thought; that is, medieval philosophers saw the earthly world as a site of continual change and constant multispecies interactions, much like the books in which they expressed these views. Many writers affirmed that events on Earth were shaped by the movements of celestial bodies and humoral vapours. To give a representative example, each sign of the zodiac was believed to rule over a region of the human body, and the position of the moon could shift humors around the body. Physicians were therefore instructed to refrain from bloodletting while the moon was in the sign associated with a given body part, a task facilitated by “zodiac man” diagrams in manuscripts.

Zodiac man from an astronomical and medical miscellany. Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, LJS 463, folio 54v.

Despite this harmony between the content and materiality of premodern texts, many medievalists were, as John Unsworth writes, “early adopters” of digital approaches, and a large amount of scholarly labour is now spent creating, studying, and teaching with digitized manuscripts. Digitization has vastly improved our ability to compare manuscripts across repositories, and it performs a crucial role in making manuscripts accessible to those without the means to visit them. Yet some scholars have questioned whether the impersonal experience of consulting a digital facsimile distorts our understanding of premodern textual culture.[i] How can we convey the earthly materiality of manuscripts when our objects of research are housed in the “cloud”?

I would not dispute the importance of accessing original manuscripts, but I believe that digital resources enable us to revive the flexible modes of reading associated with premodern manuscripts,[ii] to collaborate on these texts with a larger, more diverse community than ever before, and to problematize notions of the digital world as immaterial. To open discussions on these points, I would like to share two examples from my own projects.

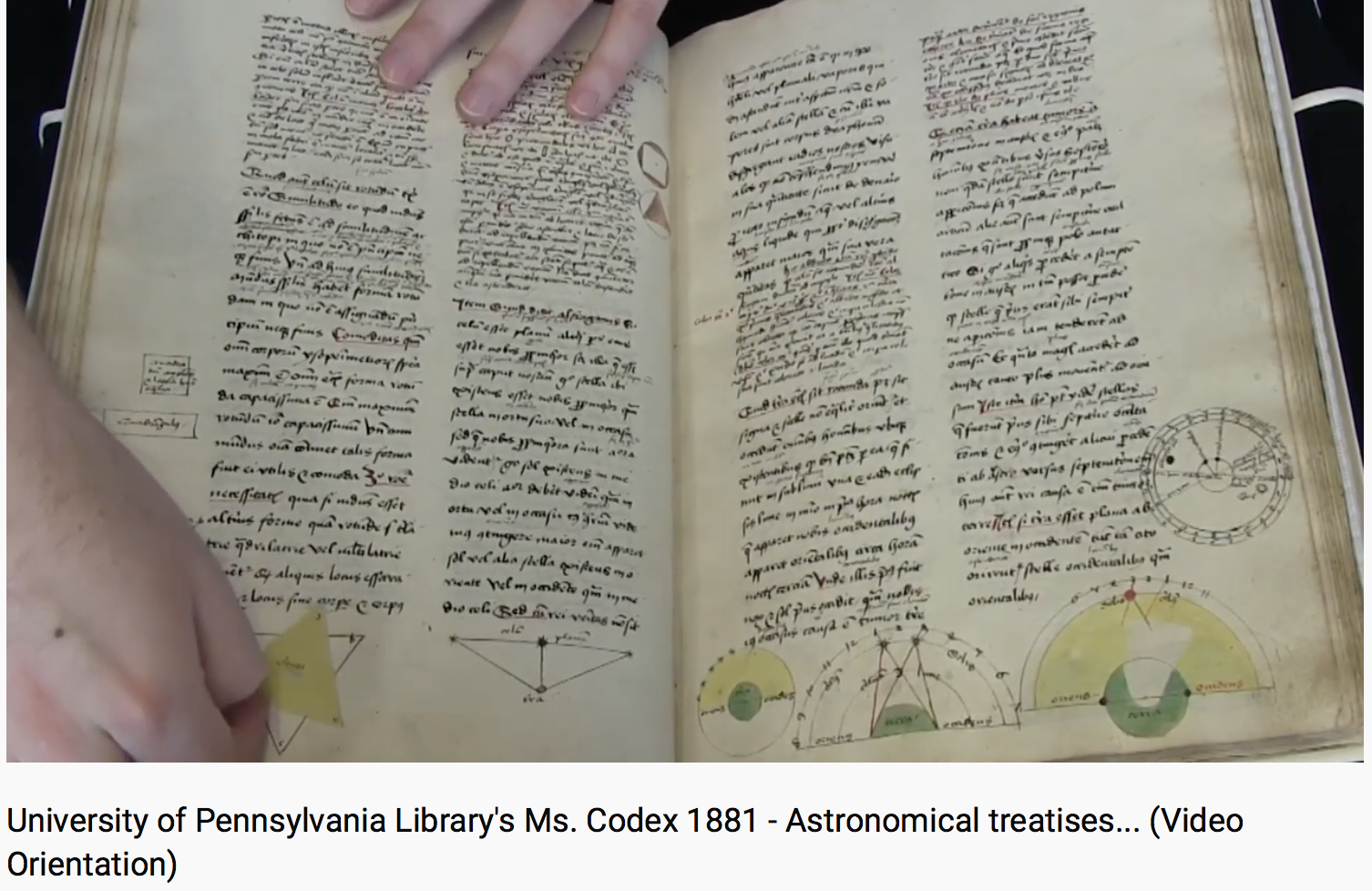

First, I believe that digitization invites us to expand our notions of “handling” manuscripts, and heightens our awareness of the physical, and even environmental, aspects of computing. Although critics have observed that digital images have an ironic tendency to eliminate the digits – that is, the tactile experience of handling these objects – this perspective neglects to account for digital resources that do emphasize touch, often by depicting an expert handling the original manuscript. As Johanna Green observes, when curators’ hands appear in images and videos of manuscripts (like those on the Schoenberg Institute Youtube channel), they serve as "haptic intermediaries" that invite viewers to imagine and re-enact these gestures using their touchscreens and trackpads. In short, touching becomes a large-scale, shared phenomenon rather than an individual one.

The Schoenberg Institute’s Curator of Manuscripts, Nicholas Herman, manipulates a volvelle in his video orientation to Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, MS Codex 1881.

In recent years, platforms have also emerged that encourage viewers to manipulate and interact with facsimiles. For instance, I used Omeka and Neatline to create a series of interactive diagrams based on the Kislak Center manuscript MS Codex 1881. Some of these diagrams can be clicked to view transcriptions and translations. Inspired by the six volvelles (rotatable discs) in this manuscript, I also created rotating diagrams, which viewers can move by clicking and dragging. All of these diagrams are available at aylinmalcolm.com/sacrobosco.

This parchment volvelle from folio 25v of MS Codex 1881 was the inspiration for a moveable facsimile.

Building on Green’s analysis of touch-based digital platforms, I would argue that resources like this website not only evoke the experience of handling a manuscript, but also highlight the physicality of modern computing. It is true that swiping up and down on a trackpad does not feel the same as turning a parchment volvelle. Yet this very discrepancy calls attention to the materiality that the notion of “cloud computing” often elides: as the viewer imagines touching this manuscript, they may also become aware of the action that they are actually performing, and by extension, of the physical infrastructures that make digital archives possible. Manuscripts are made up of earthly materials, but so are computers and data centers, and the convergence of these technologies helps to remind us of that fact.

A second example of the benefits of digital facsimiles pertains to the aforementioned fluidity of both world and text; that is to say, digital resources foster practices of sampling and sharing resembling those in which medieval and early modern readers often engaged. While working on an edition of the Kislak Center manuscript LJS 445, now available at aylinmalcolm.com/ljs445, I noticed an unusual case of damage on one page. I soon realized that an image had been carefully removed from the book, leaving only traces of a tail, ears, and two front paws.

Details of Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, LJS 445, folio 182, verso and recto.

Technically, this page depicted the constellation Canis Minor, sometimes identified as the companion of Orion or Erigone. Yet I suspect that its desecrator simply viewed it as an appealing picture of a dog and opted to save it for later reference. Moreover, the precise way that this image was extracted – by cutting or tearing along its outline – suggests that it might have been used as a toy, like a paper doll. Although we cannot be sure of the culprit’s identity, this theory is consistent with the fact that LJS 445 was annotated by two children in the late sixteenth century.

The transformations undergone by this image might be said to exemplify the fluidity of the medieval and early modern universe. Its artist represented a cluster of stars as a dog, underscoring its earthliness by depicting it running on a green field. This dog was then removed from the book, eliminating any trace of its celestial origins, and used for purposes that its creator likely did not intend; perhaps it figured in the imaginative games of children, standing in for a live animal. Yet this absent illustration also evokes the familiar contemporary experience of sharing animal pictures we find on the internet. In fact, digital images are frequently cut, copied, and reused in ways that are far removed from their original contexts, and that blur the boundaries between species and other categories, such that a marching penguin can represent the human experience of social awkwardness, or a cat with an underbite can signify irritability.

Perhaps these mutable digital environments can help us to imagine inhabiting the medieval cosmos, and to apply more flexible, interconnected – in short, more ecological – conceptual models to our own world. Perhaps digitized manuscripts in particular can encourage us to think on multiple scales, as ecological phenomena often require us to do: to contemplate the relationships between past and present, between the local (e.g. a curator touching a manuscript) and the global (e.g. a digital resource that is accessible worldwide). While they may not smell of sheepskin, it is certainly clear that digital facsimiles are no less lively than medieval manuscripts, no less adaptable, and no less capable of disrupting the orderly lines in which we attempt to describe our world.

Ursa Minor and Draco, from LJS 445, folio 178v.

[i] For examples of scholars expressing these concerns, see Anna Chen, “In One’s Own Hand: Seeing Manuscripts in a Digital Age,” Digital Humanities Quarterly 6.2 (2012); Maura Nolan, “Medieval Habit, Modern Sensation: Reading Manuscripts in the Digital Age,” The Chaucer Review 47.4 (2013): 465–76; Andrew Prescott, “The Imaging of Historical Documents,” in The Virtual Representation of the Past: Digital Research in the Arts and Humanities, ed. Mark Greengrass and Lorna Hughes (Ashgate, 2008), 7-22; Elaine Treharne, “Fleshing Out the Text: The Transcendent Manuscript in the Digital Age,” postmedieval 4.4 (2013): 465–78; Sarah Werner, “Where Material Book Culture Meets Digital Humanities,” Journal of Digital Humanities 1.3 (2012); Jonathan Wilcox, “The Sensory Cost of Remediation,” in Sensory Perception in the Medieval West, ed. Simon C. Thomson and Michael D.J. Bintley (Brepols, 2016), 27-51.

[ii] Although printing tended to produce texts that were more standardized, many print texts call attention to their materiality in creative and thematically relevant ways. For an informative reading of the relationship between early modern natural history and the materiality of the book, see Whitney Trettien, “Plant → animal → book: Magnifying a Microhistory of Media Circuits,” postmedieval 3.1 (2012): 97-118.