Interleaving Ways of Knowing a Prairie: Drawing, Data, and Plants

May 20, 2021

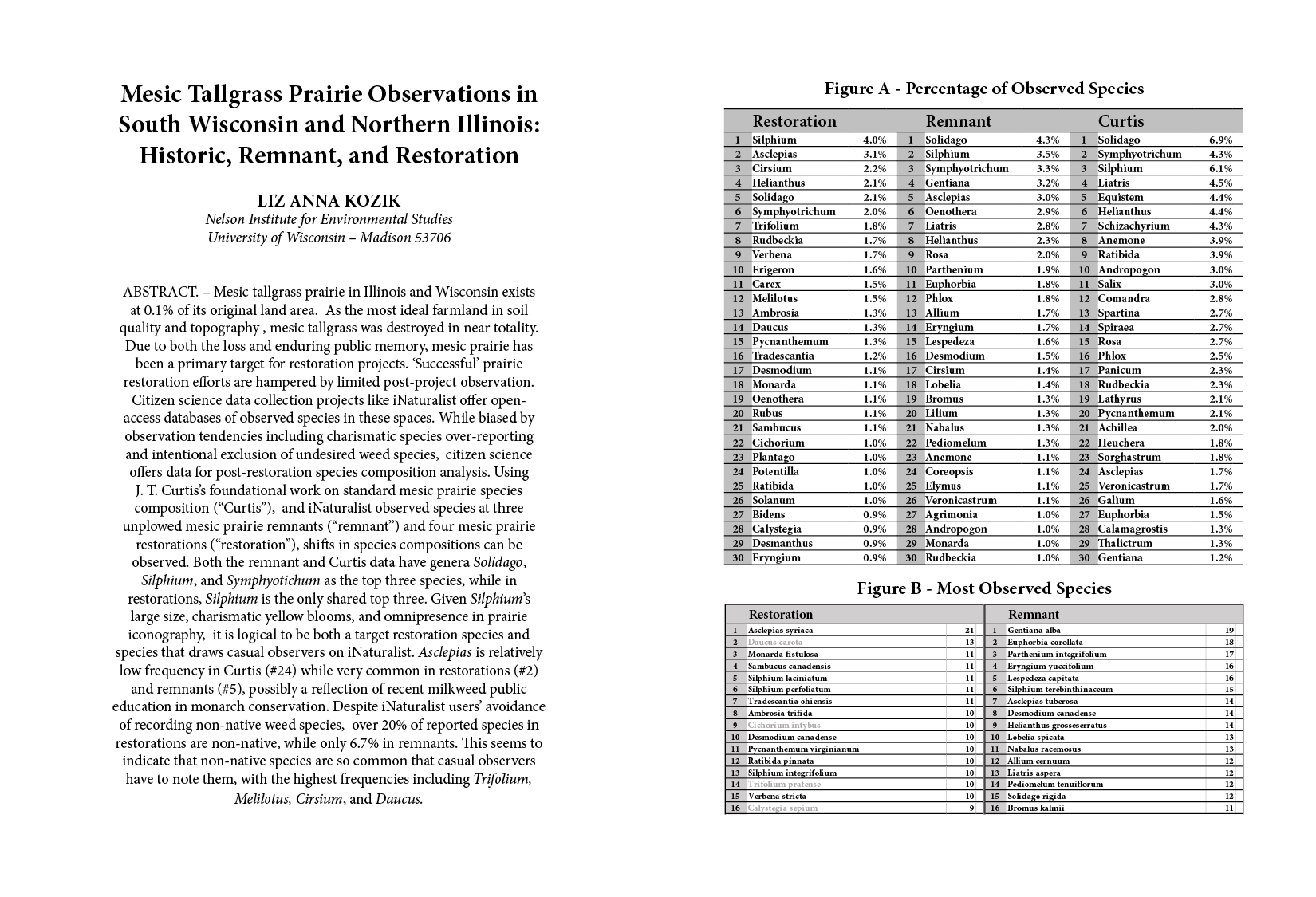

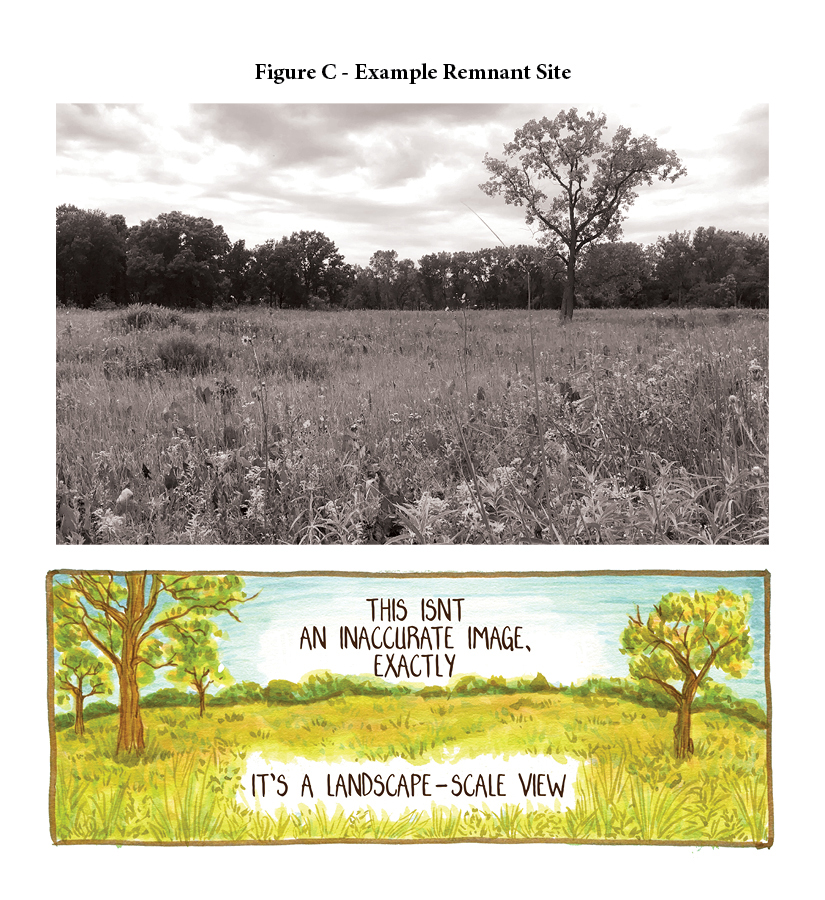

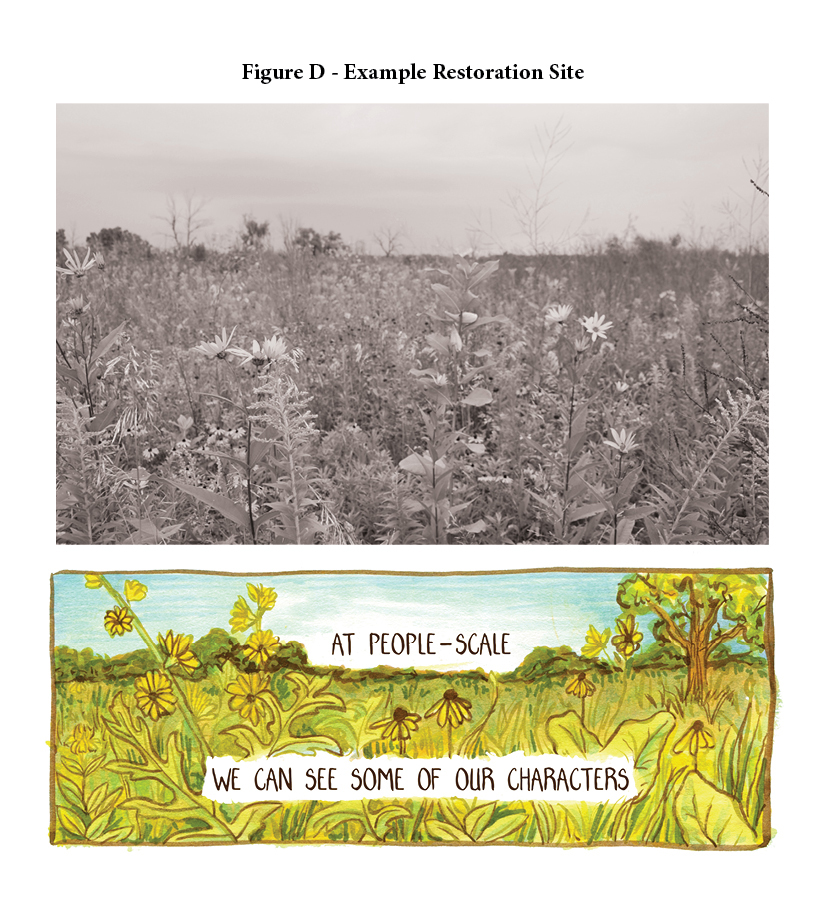

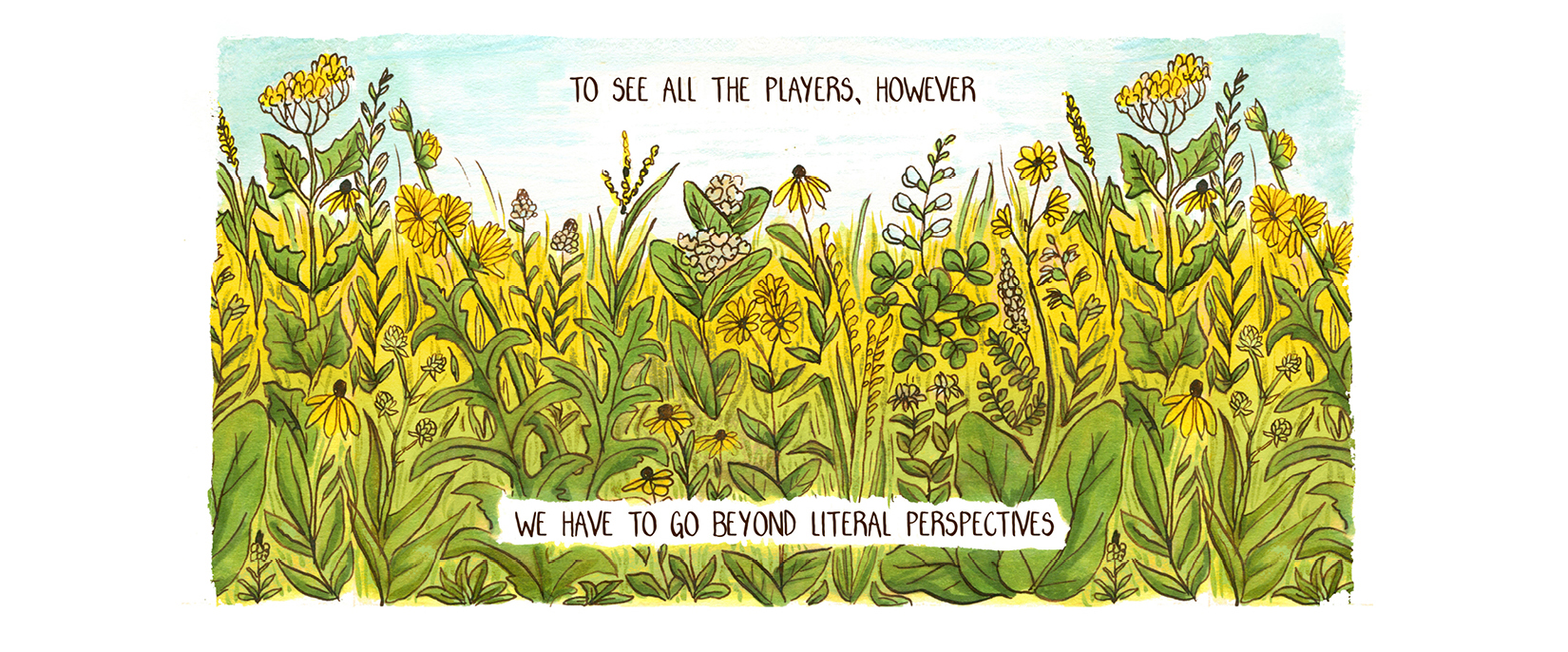

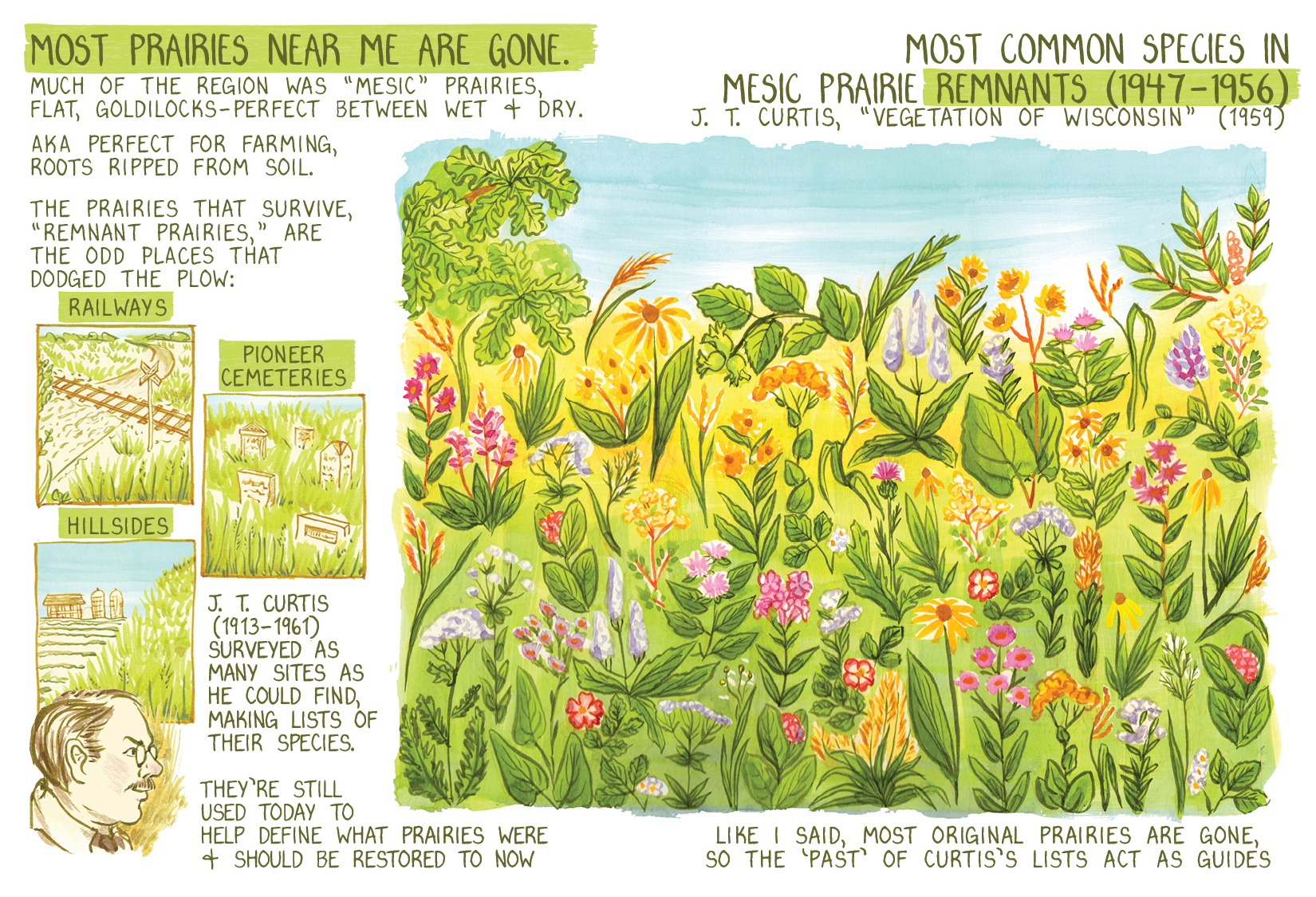

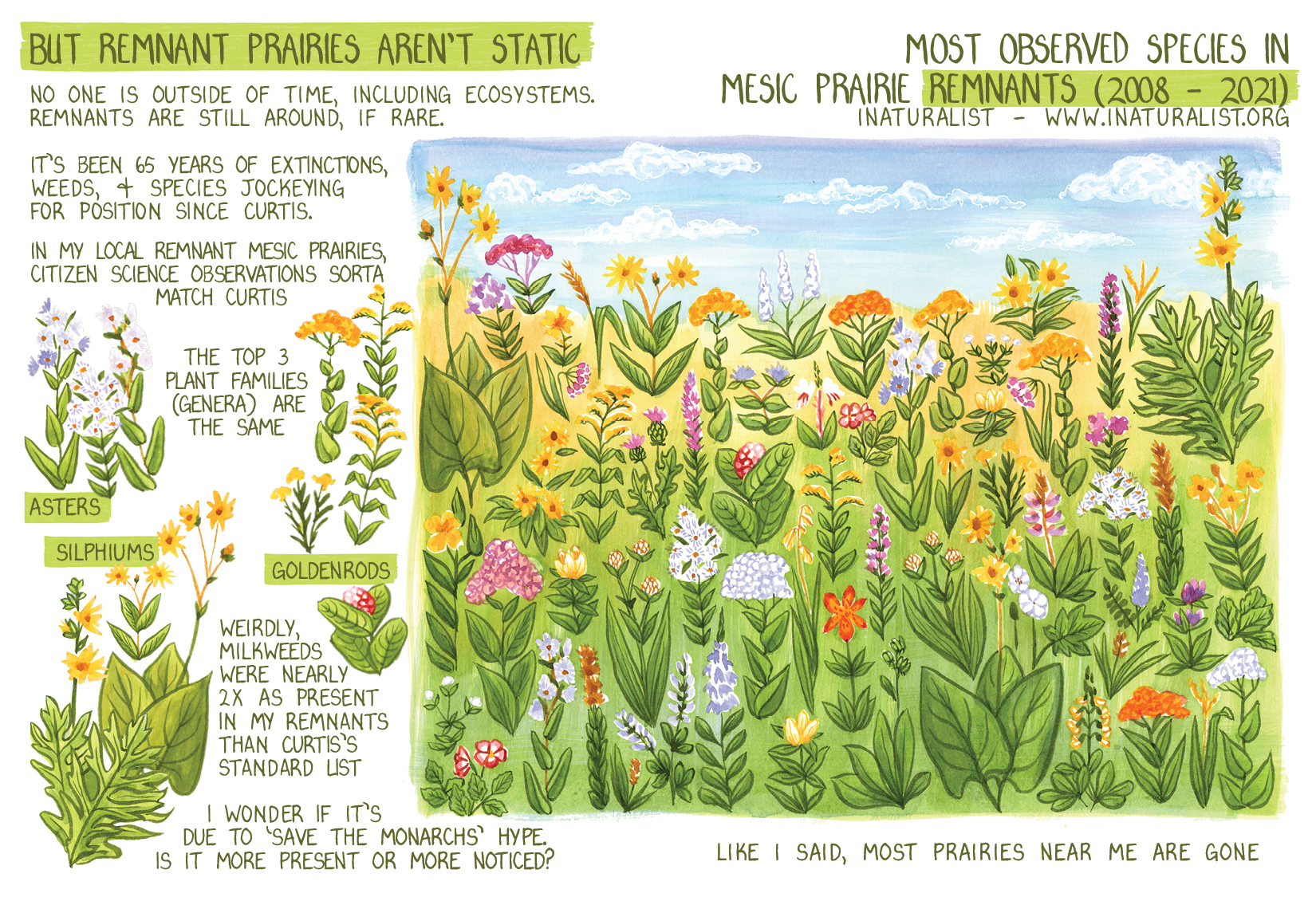

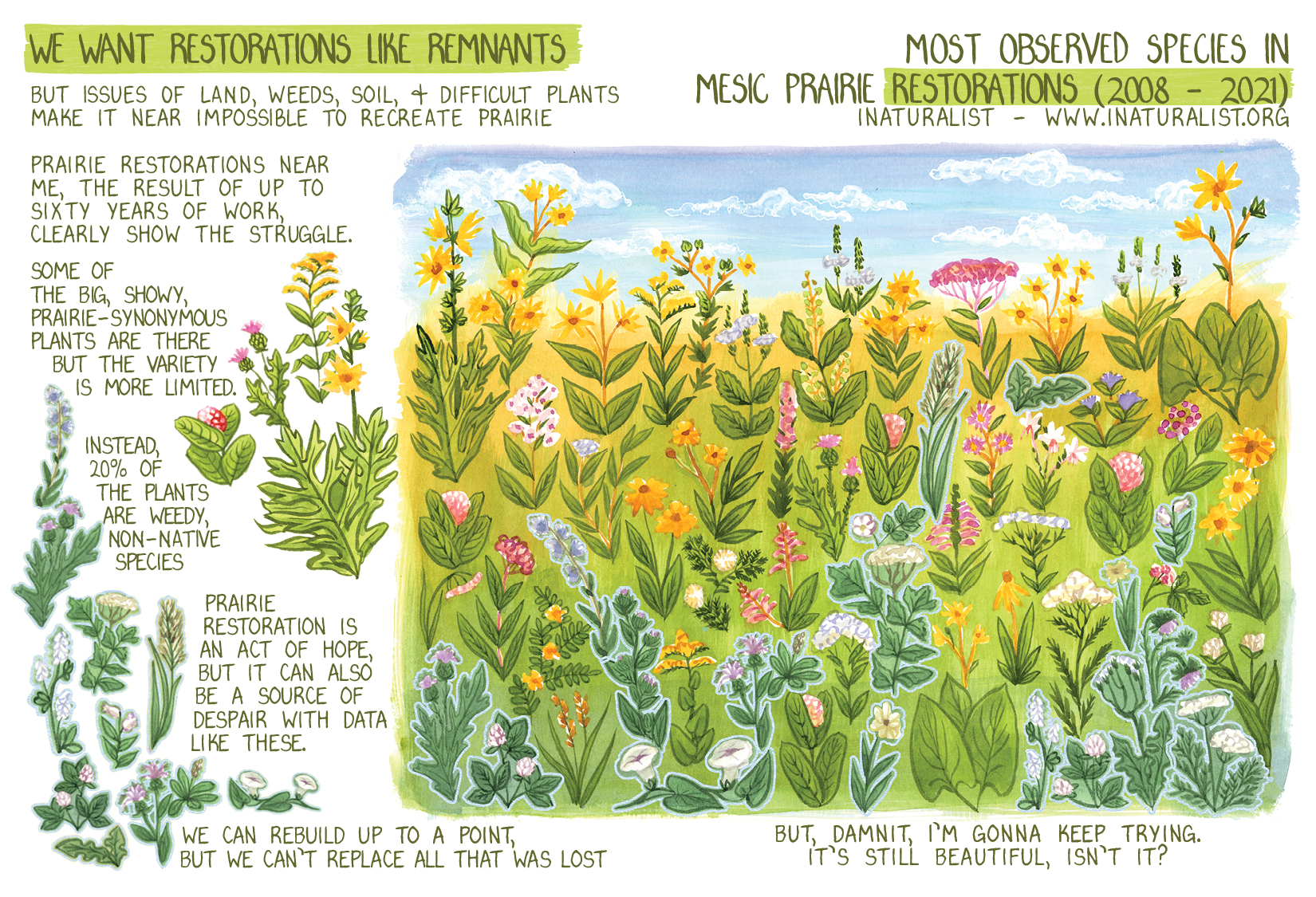

Welcome to the second of three guest posts on "The Arts of Noticing", edited by PPEH Graduate Fellow Pooja Nayak, a doctoral candidate in Anthropology and South Asia Studies at Penn. This piece by Liz Anna Kozik, a PhD candidate at the Nelson Institute of Environmental Studies at University of Wisconsin-Madison, runs an experiment for the reader: what aspects of the Mesic prairie histories, remnants, and their restorations become visible when the same dataset is presented through a formal, journal style abstract, and then explored through drawing?

For other posts in this series, see Pooja's introduction, and Part 1.

Long lists of species names and corresponding numbers make up the backbone of ecological research. Yet the living world is complex, varied across space and time in ways that numbers in spreadsheets struggle to express.

Liz Anna Kozik is an interdisciplinary scholar who works at the intersection of science communication, environmental humanities, and art. Her research focuses on the myriad culturo-scientific facets of ecological restoration in the American Midwest. Through comics and an active social media presence, she shares stories of the practices, people, and history of prairie restoration.