Reframing Humans, Animals and Land in Contemporary Brazilian and Argentinian Cinema, Essay 1: Geology, Loss, and Desire in Viajo Porque Preciso, Volto Porque Te Amo

May 8, 2019

Dana Khromov

The following post is an essay by Sebastián Figueroa, a PhD Candidate in Hispanic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. It is the first of the 5-part series "Reframing Humans, Animals and Land in Contemporary Brazilian and Argentinian Cinema". In his essay, Sebastián considers the connection between loss of love and loss of land through the narrative dialectic between a scientific state perspective and a subjective one in Viajo Porque Preciso, Volto Porque Te Amo (Karim Aïnouz and Marcelo Gomes, Brazil 2009). Included at the bottom of this post is my conversation with Marcelo Gomes, recorded in his studio in Recife, Brazil, in January 2019.

Geology, Loss, and Desire in Viajo Porque Preciso, Volto Porque Te Amo

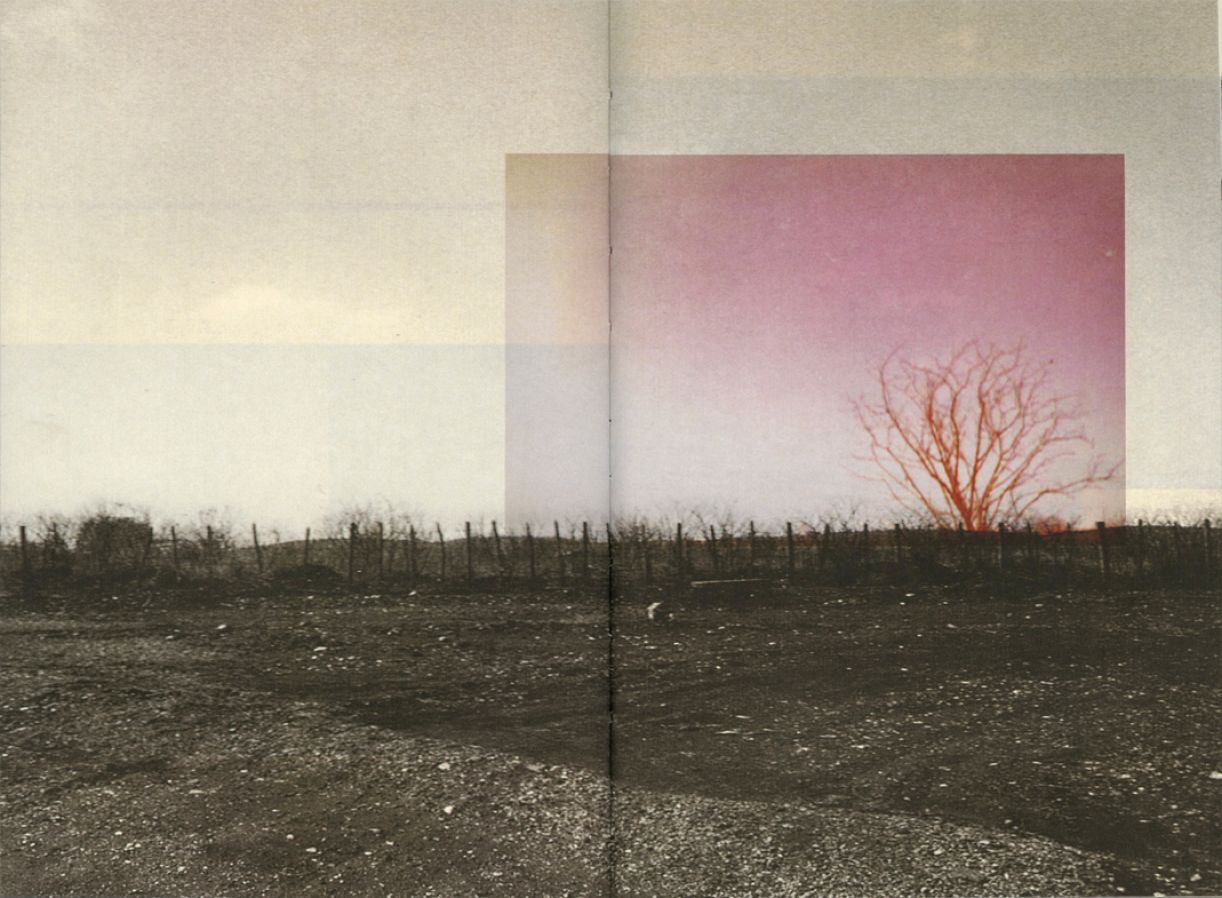

An image from "Viajo Porque Preciso, Volto Porque Te Amo", a book inspired by the film (Edições Sesc São Paulo, 2015)

Viajo Porque Preciso, Volto Porque Te Amo is a 2009 Brazilian film written and directed by Karim Aïnouz and Marcelo Gomes about José (Zé) Renato, a geologist from Fortaleza sent on a thirty-day surveying trip to the sertâo—the arid, isolated region in the Brazilian Northeast—to assess possible routes for an irrigation canal that would connect the Xexeu region with the Rio das Almas. The film is a travelogue written from the point of view of the geologist, who reflects through a melancholic voiceover—we never see his body—on what he encounters in the landscape of the solitary route BR-432 where the dam will be built, while lamenting the end of his marriage to Joanna, a botanist. In this fashion, the film presents a dialectical tension between a scientific and a subjective perspective on the landscape, which is expressed in a chaotic mixture of fiction and documentary as well as different formats and mediums such as digital video, 8mm and 16mm film, still photos, interviews, and found footage. As a result, the film develops less as a cinematic road movie than as a collage of intimate reflections provoked by the longing views of the isolated landscapes and communities of the sertâo—which can be seen more distinctly in the first version of the film entitled Sertão de Acrílico Azul Piscina, from 2004.

The first part is concentrated on the geology and geography of the arid terrain, which originated in the Cambrian period and whose tectonic structures present faults from the genesis of the Earth. The second part focuses more on the geologist’s personal encounters during his trip, particularly inhabitants of the few rural houses, gas stations and small towns. In between these two parts, the film mournfully depicts some of the people who will be forced off their land to make way for the construction of the canal. In this way, the film posits an opposition between the scientific view of a civil servant whose gaze represents the State and sees the features of the landscapes as empty abstractions that can be molded at will, and the personal view of someone who has lost his marriage and is traveling less by command than by the desire to flee and find himself able to love again, even in the wake of extinction and displacement. In fact, the film emphasizes the erotic dimension from the beginning, stressing romantic couples Zé encounters along the way to the accompaniment of popular ballads of love and despair playing on the car radio. Indeed, Zé’s view is marked by a strong male gaze, manifest in the sexualization of the landscape (soil cracks looking like vaginas, for example) and the register of encounters with sex workers, such as Patricia Simone da Silva, who shares her own ideas about love and companionship in the film’s longest interview.

Still from Viajo Porque Preciso, Volto Porque Te Amo (Marcelo Gomes and Karim Aïnouz 2009), featuring a couple that will be forced off their land to make way for the canal.

The result of the dialectical tension the film presents between the scientific view attributed to the state and the subjective view of the solitary individual is a presentation of the sertão landscape not as a metaphor of isolation and abandonment, as it has been traditionally viewed in Brazilian discourses of modernization, but as one of survival and embrace of life notwithstanding the catastrophic changes we experience in both our personal lives and the environment. On the one hand, the loss of companionship and love functions to express the loss of landscape and community taking place in the region. Moreover, the film examines how in the context of large anthropogenic changes to environment, subjective problems acquire a geological dimension, connecting personal time with deep time. The failed marriage between a geologist and a botanist may thus be a metaphor of the break between geos and bios put forward by extractive capitalism. On the other, the trip becomes less a geological survey than an essay about the possibilities of life on the verge of an eco-catastrophe. However, the film’s end might be presenting a more pessimistic solution to the riddle posed by the loss of landscapes and community as a result of large scale human intervention in the sertâo. Looking at the quiet Rio das Almas, the geologist imagines himself instead in Acapulco, jumping from the cliffs to dive into the deep sea. While this can be read as a metaphor for diving into life again, one cannot help but think that it might also be suggesting the opposite.